On the 25th of June, 1950, the North Korean people’s Army (NKPA) invaded South Korea by crossing the 38th Parallel, the line of latitude that is 38 degrees north of the equator. At the end of World War II, Korea was divided into two nations along the 38th parallel; North Korea was supported by Russia, and South Korea was supported by the USA. Bringing in 135,000 troops, the North Koreans encountered little opposition and entered Seoul on the 28th of June, 1950.

This forced the American army into the war, where they found the NKPA were no pushovers but fought fiercely, causing many casualties among the American and South Korean forces. In July 1950, the Americans and other allied forces had retreated to Pusan, the only deep-water port in South Korea.

Things looked bleak for the Allied forces, but they had a significant weapon in Lieutenant General Walton Walker, whose combat skills enabled the Allied forces to fight an excellent defensive battle. The goal was to hold off the North Koreans and protect Pusan while the UN mustered reinforcements of both men and equipment to bolster the meagre number of American troops fighting since the start of the Korean War.

It was during this time that Walker issued his famous stand or die order, “We are fighting a battle against time. There will be no more retreating, withdrawal or readjustment of the lines or any other term you choose. There is no line behind us to which we can retreat. There will be no Dunkirk; there will be no Bataan. A retreat to Pusan would be one of the greatest butcheries in history. We must fight until the end. We will fight as a team. If some of us must die, we will die fighting together. I want everybody to understand we are going to hold this line. We are going to win.” And they did win, or rather hold the line, and they did so in fighting the first major battle of the Cold War.

General McArthur, the only five-star general still on active duty, had laid plans to launch an offensive in the North Korean rear. At Inchon on the 15th of September, he launched his invasion with the so-called X-Force. Walker and his 8th Army broke out of Pusan the following day, being able to link up with McArthur on the 27th of September. By October 19th, the 8th Army had seized Pyongyang, the capital of North Korea, and the Americans were convinced that the war was over and that peace would be declared. They were sadly mistaken – on November 26th the Chinese Army came to the rescue of the North Koreans and pushed the 8th Army back below the 38th parallel.

Early in January 1951, the UN forces withdrew from Seoul after the combined Chinese and North Koreans forces attacked. By March of the same year, after bitter fighting, the UN forces retook Seoul and once again pushed the Chinese/North Korean forces back to the 38th parallel. In the first half of 1951, there was bitter fighting along the 38th parallel as the Chinese attempted to force the Americans back down the peninsula By July 1951, armistice negotiations started.

The negotiations were interrupted by attacks by Chinese and later by UN attacks on each others hills and fortified positions. Eventually, on July 27, 1953, an armistice agreement was signed at Panmunjom, a village that straddles the border. Both sides agreed to withdraw a short distance to create a demilitarized zone between the two Koreas; a situation that still exists today. No formal peace treaty was ever signed, and the De-Militarized-Zone is the most heavily fortified area in the world.

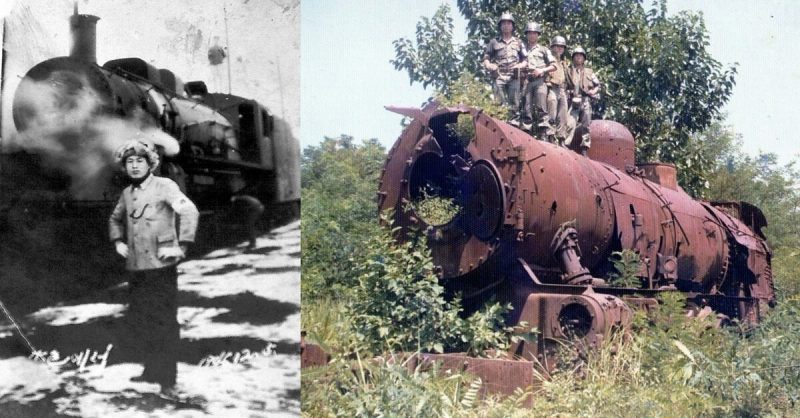

While these events were taking place, they were supported by ordinary men doing the very best job that they could. One of these men was Han Joon-ki, a locomotive driver. Han was born in Japan to Korean parents, and in 1943 he started working for Japan Railways, eventually making it to being a locomotive driver. He was in Nagasaki when the atomic bomb detonated and destroyed the city and, along with it, thousands of people. With the destruction of the city and Japan’s surrender, Han left Japan and returned to Korea where in February 1946, he joined the Korean National Railroad as a locomotive driver. He was very happy hauling trains behind his locomotive, and the momentous events that happened around him passed him by completely.

The United States accepted the surrender of the Japanese troops stationed in Korea and arranged for them to return to Japan. The country would be divided along the 38th parallel; the North would fall under the Soviet sphere of influence, the South under the American influence. In 1948, Syngman Rhee was elected as President of the Republic of Korea. At the same time, Russia was championing Kim Il Sung to become the leader of the North Koreans.

Han was living in Seoul, and one day he noticed that most of the US troops had left, but he did not recognize the tanks driving around his beloved city. At one of his stops at Seoul Station he was told, by a friend, that they were North Korean. The fact that war had once again come to a land that he lived in was brought home to him on 28th of June 1950.

He was in charge of a train travelling toward the Han River, and when he was close to Yongsan Station, he heard a loud explosion. He then noticed that the rail tracks were bent. He discovered that South Korean soldiers had destroyed the rail bridge over the Han River in an attempt to stem the tide of North Korean troops. This action disturbed Han, as he realized that, had he not noticed the destruction of the tracks, he and his train may well have plunged into the river at the destroyed bridge.

Han did his work for the war effort by transporting supplies up as far as Pyongyang. Though he rarely saw any fighting, he witnessed the terrible side effects of the war. The North Korean people knew that his train would travel south and in an effort to flee the fighting they would climb on top of the train, hoping to get a lift to the south. Sadly, many people fell off the roof, and he often saw the bodies lying next to the tracks. In spite of the best efforts of the US forces, more and more people tried to get a ride back to the South and the perceived safety it offered.

Han’s belief that the north and south could be united was shaken in October 1950 with the arrival of Chinese forces to support the North Korean army. If his belief had been shaken, it was dealt a death blow on the eve of 1951. He had completed a supply run to Hampo in North Korea and was returning to Munsan. As there was nowhere to turn around in Hampo, he was running the train in reverse when he was stopped at Jangdan Station.

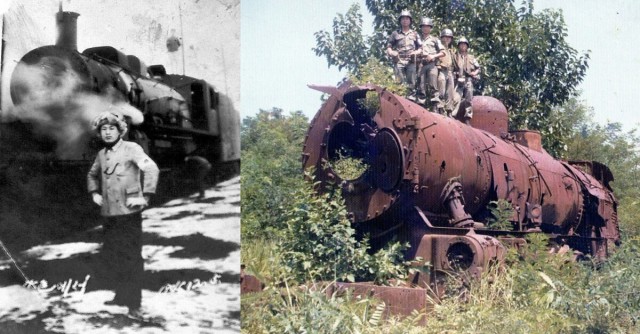

He climbed down from the engine to find out what was wrong and was stunned when American troops surrounded and then opened fire on his treasured locomotive, utterly destroying it. He stood there astounded. “They just started shooting the train,” he said. “There was nothing I could do. They could have always moved the train to another place. I really don’t understand why they had to do that.” The Americans destroyed the locomotive to keep it from falling into the hands of the North Koreans.

More than 1020 bullet holes of the locomotive and its bent wheels show the cruel situation at the time.

This brave little engine that had carried supplies for the UN effort was now abandoned west of Panmunjom in what became the demilitarized zone. There it sat for the last sixty years – it is now a rusted, gutted hulk, but it may soon have shiny, new neighbours. In June 2000 there was a meeting between the presidents of the two Koreas; they agreed to establish a railway line and highway connecting the two countries. Han, once again, had dreams of the two nations becoming united.

In June 2006, the engine was finally removed from the DMZ and moved on a truck to Imjingak where it was preserved, not restored. It is now on display at Jangdan Station near the DMZ.

Han is representative of most people within the south of Korea. They all hope that one-day sanity will prevail, and the Korean people will, like the Germans, resolve their differences and find that they are more similar than different. Han’s locomotive may be lying rusting away, but it has excellent company.

The demilitarised zone, having seen no human interference for the last sixty years, has become a haven for wildlife. With nature showing the way, one can only hope that mankind follows, and peace once again reigns. Han can then drive his locomotives north and then return safely to the south once more.

“Steam Locomotive at Jangdan Station of the Gyeongui Line – 7 June 2011” by Dushan Hanuska from Sydney, Australia – Bullet holes. Licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.