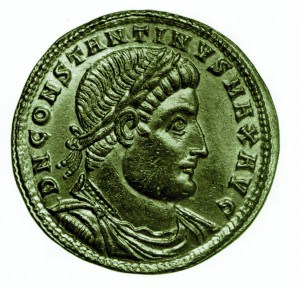

The Great Emperor Constantine’s victory at Milvian Bridge in AD 312 forever changed the path of Western civilization as we know it.

The Great Emperor Constantine’s victory at Milvian Bridge in AD 312 forever changed the path of Western civilization as we know it.

by Ludwig Heinrich Dyck

In AD 305, there occurred an event unprecedented in the history of the Roman Empire. Emperor Diocletian voluntarily abdicated to live the simple life of a farmer on his country estate. Diocletian wasn’t just any emperor; he was the founder of the Tetrarchy, by which the empire was ruled by four co-emperors, and brought order to the political turmoil of the late third century. But it was Diocletian’s strong leadership, not the system itself, that made the Tetrarchy work. If anything, the Tetrarchy ensured that following Diocletian’s retirement the Empire would again plunge into civil war.

So it was that a year two new emperors arose: one in Britain, Flavius Valerius Constantius, destined to go down in history as “Constantine the Great”; the other in Rome, “Prince of the Romans,” Marcus Aurelius Valerius Maxentius. Both were sons of former emperors and both were made emperor by their troops. Initially allies, they were set to collide as each sought to become the undisputed master of the Western Roman Empire.

On July 25, 306, at York on the northernmost frontier of the Roman Empire, Augustus Constantius Chlorus lay dying. At his bedside stood his many children. All but one were teenagers or younger, the offspring of Chlorus’s second marriage to the noble Theodora. In stark contrast, Constantine, the sole child of Chlorus’s first marriage to the barmaid Helena, was 32 years old.

Constantine’s Rise to Power and Respect

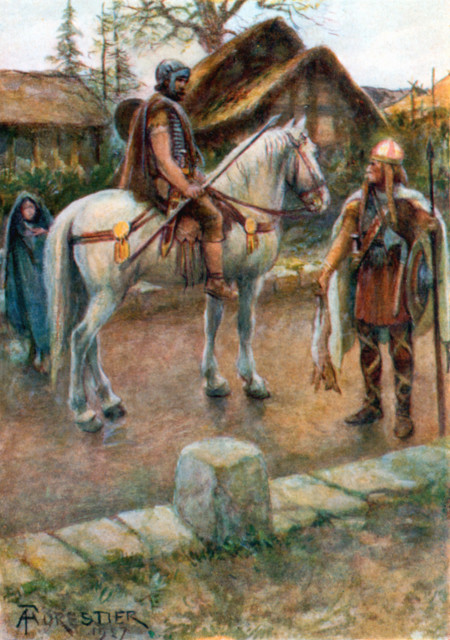

Constantine’s tall, muscular frame bespoke a life of hard fighting and campaigning. He and his father had recently returned from warfare against the Picts. Those wild marauders struck south into Roman Britain, but Chlorus and Constantine flung them back across Hadrian’s wall. Chlorus could not have wished for a worthier heir. Before the old emperor breathed his last, he flung his arms around Constantine and named him his successor.

During the battles against the Picts, Constantine won the respect and admiration of the troops. So much so that his barbarian friend, King Crocus, commander of the German cavalry, lost no time in proclaiming Constantine as the new Augustus. The Imperial purple toga was clasped around his shoulders while his face was still wet with tears of sorrow over his father’s death. When he emerged to address the troops, they raised him high on their shields and acknowledged their approval with a thunderous cheer. Their cry soon spread throughout Chlorus’s domains in Gaul where one province after another heralded allegiance to his son.

Far to the south at Rome, Maxentius fumed over Constantine’s succession. To him it was intolerable that “the son of a harlot”¹ had become emperor, while he himself had been considered unsuitable to succeed his retired father, Emperor Maximian. Determined to usurp Imperial power, Maxentius became the figurehead of a popular revolt at Rome.

The revolt was brought about by the loss of Rome’s prominent political status and its five-century-old exemption from taxation. Under the Tetrarchy, Italy became just another province with the Imperial residence at Milan. The people howled in protest that Diocletian, an Illyrian peasant, dared to dictate the affairs of noble Rome.

With Rome’s decline and the absence of a resident emperor, the superfluous Praetorians (the Imperial Guard of Rome) were reduced to the rank of a garrison. They hoped that Maxentius would restore to Rome and to themselves the glory that once had been theirs. On October 28 the Praetorians and all of Rome proclaimed Maxentius, the “Prince of the Romans,” as emperor.

Southern Italy and Africa declared for Maxentius. The problem was that they already belonged to another emperor who ruled out of Milan. Such legalities mattered little if Maxentius could back his claim with martial might. To do this he needed, and got, powerful allies. His battle-tested father, Maximian, came out of retirement to lead his son’s armies. Another ally was found in Constantine, who married Maxentius’s sister and in return acknowledged Maxentius’s position.

A Battle of Two Emperors

Maxentius’s usurpation precipitated the breakdown of the Tetrarchy and led to a convoluted civil war. Under the original Tetrarchy there were supposed to be two Augusti (senior emperors) assisted by their two Caesars (junior emperors). In the ensuing four years, the lesser title of Caesar became obsolete and everyone became an Augustus; during one year there were as many as six. To make matters worse, while emperor fought emperor, the frontiers strained under the pressure of hostile barbarian tribes.

Brutal campaigns against Franks and Alamanni along the Rhine demanded Constantine’s full attention and initially kept him out of the civil war. In contrast, Maxentius was at the center of the Roman infighting. With his father’s help he successfully strengthened his power base in the west, repulsed two invasions of rival emperors, killed one of them, annexed northern Italy, and gained Spain.

Fate turned against Maxentius when Spain declared for Constantine, who consequently broke off relations with Maxentius. Worse was in store when Maxentius’s father attempted to regain Imperial power for himself. In front of the assembled troops of Rome, Maximian tore the purple from his son’s shoulders. To Maximian’s dismay the army remained loyal to his son. In fear of Maxentius’s wrath, Maximian fled to the safety of his son-in-law Constantine. Hungry for power, Maximian treacherously repaid Constantine by attempting yet another palace coup. The debacle ended with Constantine laying siege to Maximian at Marseilles and apparently having him executed in 310.

Maxentius pretended grief over his father’s death and foolishly lashed out at Constantine, whose name he removed from all inscriptions and commemorations throughout Italy. The same year, to add to Maxentius’s woes, Africa, with its crucial grain supply, defected and proclaimed yet another Augustus. Although Maxentius recovered Africa and exacted terrible retribution on Carthage, Rome suffered through severe starvation and riots.

Maxentius’s answer to all his problems was to degenerate into a tyrant. The Praetorians carried out massacres to suppress the people, and his numerous mercenaries caroused throughout Italy at will. From the Senate he extorted “free gifts” and threw into the dungeons or murdered anyone who did not agree with his every whim.

Like a wolf senses his wounded prey, Constantine sensed that Maxentius had become weak. Rome and Italy seemed ripe for the taking and in 310 he gained the approval of the Augustus of the Danube region, Valerius Licinius, to march on Italy. Such approval was needed because Italy theoretically belonged to Licinius. However, he had his own hands full with another rival Augustus in the east and was only too happy to have Constantine deal with the troublesome Maxentius. To strengthen their bond, Constantine promised his sister’s hand in marriage to Licinius.

In the fall of 311 Constantine left for Colmar. There he spent the winter planning his strategy and gathering supplies for his coming campaign into Italy. Constantine probably commanded over 100,000 troops. Most of these were needed to guard the Rhine. His comitatus, or mobile field army, including his scholae personal guard of German cavalry, comprised only a quarter of the total available forces. To augment his field army, Constantine levied additional Germans and Gauls to give him almost 40,000 men for the invasion of Italy. Nearly all of them were veterans, hardened by years of warfare along the Rhine and in Britain.

Awaiting him in Italy would be Maxentius’s army, whose numerical strength was roughly on par with Constantine’s. However, Maxentius would be on the defensive and thus could count on the use of his entire army. The bulk of the latter was concentrated in the northeast Italian province of Venetia, where Maxentius wrongly expected an attack from Licinius.

Liberators, Not Conquerors

According to custom, Constantine consulted soothsayers before marching on Italy. Their warnings were ominous and not easily ignored in an age of superstitions. Regardless, in 312 Constantine led his army across the Alps via the Mont Cenis Pass, no doubt hoping for a quick victory to dispel any misgivings among the troops.

Thanks to the excellent Roman roads, Constantine descended onto the plain of Piedmont before Maxentius knew what happened. Constantine wasted no time in assaulting Susa, the first enemy city in his way. The gates were set aflame and, supported by a barrage of stones and arrows, his soldiers stormed up ladders and cut the garrison to pieces. To spare the civilian population, Constantine kept his troops from plundering the city. Constantine told them that they were liberators, not conquerors.

Forty miles from Susa a more difficult task awaited him. Drawn up in front of the walls of Turin in a convex wedge was an army of Italians. Infantry formed the wings and, more worrisome, a large corps of clibanarii the center. Originally of Persian origin, the fearsome clibanarii were heavy lancers. Both rider and mount were fully armored in bronze and iron scale mail.

Constantine arrayed his army in a concave formation, with infantry in the center and probably cavalry on the flanks. His horsemen were likely outclassed and outnumbered by the clibanarii. Perhaps because of this, Constantine chose to avoid a cavalry versus cavalry engagement. Instead, he had another plan.

The clibanarii thundered down upon Constantine’s infantry ranks like an avalanche of flesh and iron. Constantine knew full well that if asked to hold the line, his infantry might scatter in fear of being ridden down. Instead he pulled their ranks inward from the center to form a rough V shape. As expected the clibanarii continued to ride straight into the V, exposing their flanks. This was exactly what Constantine had hoped for. Groups of barbarians, swinging huge iron-knobbed clubs at shoulder height, assailed the enemy horsemen. The clibanarii were knocked off their mounts, bludgeoned to death on the ground, or trampled by their own confused steeds. Others tottered half-dead in their saddles. Those who were not unhorsed beat a hasty retreat to the city gate, only to find that the citizens refused to let them in. While the clibanarii went down in defeat, Constantine sent his cavalry wings forward and outward to encircle and finish off the remaining enemy infantry.

The citizens of Turin opened the city gates and welcomed Constantine as their emperor. Their example was followed by many other northern Italian cities, which sent embassies and supplies. Constantine next moved on to Milan, where the leading men greeted him in honor to the exuberant cheers of the populace. Constantine remained at Milan for a few days, giving his troops some well-deserved rest.

Verona Proved a Worthy Challenge for Constantine

From Milan, the Aemilian and Flaminian highways put Constantine about 400 miles from Rome. However, to the east, at Verona, Prefect Ruricius Pompeianus, one of Maxentius’s most able generals, hastily assembled what armed forces he could from Venetia. Not wishing to have Pompeianus follow in his rear and risk being caught between Pompeianus and Maxentius’s army at Rome, Constantine moved eastward to first clear Venetia of the enemy. Near Brescia he skirmished with some enemy cavalry sent there by Pompeianus. Pompeianus probably hoped to further delay Constantine’s approach, but his cavalry faltered at the first onset of Constantine’s legions and made a hasty retreat back to Verona.

Verona proved a daunting task for Constantine. The Adige River flows south from the Alps and at Verona bends toward the southeast. It effectively blocked the city from the west and south and allowed supplies to come in from the east. Constantine left part of his troops in “siege” position on the far side of the river from the city. With the remainder he marched north in search of a suitable crossing. The rough waters of the Adige, with its strong currents and numerous eddies and whirlpools, frustrated several attempts at reaching its eastern bank. It was not until Constantine neared the foothills of the Alps that he was able to ford the river. From there he descended south to lay siege to the eastern walls of the city and sever its supply line to the rest of Venetia.

Infected by the remnants of the beaten cavalry from Brescia, morale in the city rapidly declined. A sally from the city only resulted in heavy casualties. Constantine’s troops pushed the assault with such vigor that it seemed only a matter of time before Verona’s defenses cracked. Pompeianus knew that reinforcements were needed. Evidently, these were close by for Pompeianus secretly fled from the city, and just a few days later returned at the head of a large army.

The sun was setting and darkness began to shroud the land when Pompeianus’s tired soldiers and horses arrived. Worried about besieged Verona, Pompeianus was eager for battle. So was Constantine, who advanced at the head of his best troops. Behind them the remainder of his legions continued the siege. Caught between Pompeianus’s relief force and the walls of the city, there could be no thought of retreat for Constantine, only victory or death.

Constantine Stood Covered in Blood Among His Men, Victorious

Pompeianus’s army was so large that Constantine was forced to reduce the second of his two battle lines to extend the first. Only then did the width of his first line match that of the enemy. Such tactics proved scarcely necessary. The battle lasted deep into the night and in the darkness, chaos reigned. Trumpets blared, swords clashed, men cried, and pure courage mattered more than battle maneuvers.

None surpassed Constantine in valor that night, for he was not a commander who safely watched the battle from afar. Reckless for his personal safety, blade in hand, Constantine tore into the enemy ranks. Like some crimson whirlwind of destruction he left a grim path of slaughter. Missiles and swords passed about him, but none could find their mark. His eyes gleamed with the madness of the berserk, and woe to any that faced his fury.

When finally the din of battle died down, Constantine, his armor smeared with blood, stood panting among his victorious men. His example no doubt inspired the rank and file but the legionary officers and tribunes bewailed that Constantine should so foolishly risk his life. Constantine had little patience for their grumbling and, with barely a rest, hastened back to press the siege of Verona.

The light of dawn revealed the dreadful destruction of Pompeianus’s army, among the dead of which was Pompeianus himself. With no hope left, Verona surrendered. The remnants of Pompeianus’s army were placed in shackles to prevent them from fighting for Maxentius elsewhere.

After taking Verona, Constantine continued to push eastward past Aquileia, which capitulated, and all the way around the Gulf of Venice to Trieste. From there he swung back west to take Ravenna and then Modena. Venetia was subdued and the Via Flaminia was freed of the enemy. Nothing stood between Constantine and Maxentius at Rome.

While his troops fought and died for him in northern Italy, Maxentius heeded the advice of his generals and remained at Rome. The effeminate Maxentius had no great desire to lead his troops anyway, preferring to indulge in a life of pleasure. But the news of his defeats at Turin and Verona and the rapid approach of Constantine was not lost on the Roman people. There were riots in the streets and shouts of “Constantine cannot be conquered” during the games. Even Maxentius at last began to realize that something had to be done.

Visions and Prophecies

According to most Christian historians and even a few pagan ones, Maxentius attempted to ward off the approach of the conqueror with morbid occult rituals—casting spells, summoning demons, and sacrificing unborn babies in hopes of invoking supernatural aid. Most of this was pure Christian propaganda aimed at vilifying the “pagan” Maxentius. What Maxentius did do was consult the Sibylline Books.

According to most Christian historians and even a few pagan ones, Maxentius attempted to ward off the approach of the conqueror with morbid occult rituals—casting spells, summoning demons, and sacrificing unborn babies in hopes of invoking supernatural aid. Most of this was pure Christian propaganda aimed at vilifying the “pagan” Maxentius. What Maxentius did do was consult the Sibylline Books.

The legendary prophetess Sibyl of Cumae presented these tomes to the last of the Roman kings. For eight centuries thereafter, the Senate consulted the verses for answers whenever a crisis threatened Rome. They now told Maxentius that “the enemy of Rome would perish.” Even though Maxentius had amassed ample corn supplies from Africa and the islands in anticipation of a siege, the seemingly favorable prophecy and increasing unrest in the city convinced him to seek out Constantine instead.

Some time before the battle Constantine received divine guidance of his own, his famous “vision” that would change the course of history. The Christian scholar Lactantius wrote a year or two after the battle that Constantine was told in a dream to put the heavenly sign of Chi (X) and Rho (P), the first two Greek letters in the name of Christ, on his soldiers’ shields. In the Life of Constantine, written after Constantine’s death, the Christian historian Eusebius added that Constantine told him of a cross of light that appeared in the heavens above his army and subsequently became his war standard.

The reason for Constantine’s vision may have been his religious uncertainties and his intense desire to receive a favorable sign before his final reckoning with Maxentius. On his way to Rome, Constantine prayed diligently and thus was “ready” for a vision. It would not be the first time he was “divinely” aided. During his Frankish campaign he received similar aid from the ancient sun god Helios. Constantine may have even considered Christ one of Helios’s incarnations. Indeed, if the cross of light was not a fabrication, it could have been a rare “halo phenomenon” caused by ice crystals in the sun’s rays, similar to a rainbow. More mundanely, Constantine may have simply wished to endear himself to the large Christian faction of Rome. The true events may never be known. What mattered is that Constantine’s troops went into battle with the Chi-Rho emblazoned on their shields.

Resplendent in a gold-embroidered purple cape and ornamented armor, Maxentius led his army across the Tiber at the Milvian Bridge. Here, a few miles from Rome, he planned to bar Constantine’s advance. Maxentius deployed his army with its back to the river. To facilitate a speedy crossing in the event of a retreat, he built another bridge, a wooden pontoon bridge, beside the narrow Milvian stone bridge. The pontoon bridge was so designed that iron rivets could be withdrawn to break the bridge in the middle and cut off a pursuing army.

On October 28, 312, the armies met. Constantine for one was glad that his foe chose to face him in the open. It meant that Constantine would not have to deal with Rome’s redoubtable defenses and at the same time spare the city the hardships of a siege. Avoidance of a siege was all the more welcome since the need to garrison conquered cities and casualties suffered during the campaign meant that Constantine’s army had probably dwindled to about 30,000 men.

Rome’s Praetorians Made (and Unmade) Emperors

Maxentius’s losses in northern Italy had been much greater, but so vast was the treasury of Rome that he was able to raise yet another formidable army. Its ranks included allied Tyrrhenians and Sicilians, and Carthaginians and Numidian and Moorish light cavalry from Africa. In addition, Maxentius also had the Urban Cohorts (Rome’s paramilitary police) and his Praetorian Guard.

For centuries, the Praetorians made and unmade emperors. Restored to perhaps 15,000 men by Maxentius, they now prepared to fight their most important battle. Not only their own future, but the prominence of the Eternal City of Rome and the Western Empire was at stake.

The proud guardsmen wore white tunics with stripes of Imperial purple underneath scale mail cuirasses. White plumes or crests decorated their helmets. Their painted shields might have sported scorpions, the birth sign of Emperor Tiberius, one of the founders of the guard, or Hercules, the patron deity of Maxentius’s family.

Both sides positioned their cavalry on their flanks and the infantry in the center. Maxentius enjoyed the numerical advantage, and was able to equal the breadth of Constantine’s line with unusually deep ranks. This was a common sign of unreliable troops since the back ranks would forestall those in the front from fleeing.

Constantine personally led his cavalry against that of the enemy. Riding at the vanguard, his gold-gilded armor sparkled in the sun’s rays. From walk to trot, Constantine’s barbarian horsemen accelerated to a gallop and sliced through the enemy ranks. The Numidian and Moorish light cavalry were no match for Constantine’s Celts and Germans, or for Constantine himself. His spear struck down many foes, to be unhorsed and trampled beneath his steed’s hooves. As long as his cavalry stood their ground, Maxentius had some chance of victory, but when the Numidians and Moors bolted in flight all hope was lost.

Constantine’s infantry joined the fray while his cavalry stormed around the flanks of Maxentius’s infantry. About to be enveloped in a pincer movement, Maxentius’s auxiliary infantry and Urban Cohorts broke in panic. In a mad strive to escape the enemy, they crowded upon the pontoon bridge. Either Maxentius’s engineers lost their nerve and drew the iron rivets too early or the wooden beams gave way beneath the great weight. The bridge collapsed and hundreds of men and horses plunged into the depths. Among them was Emperor Maxentius, who was pulled under by his heavy armor. Beside the broken pontoon bridge, the congested old stone bridge turned into a deadly bottleneck. Men were crushed to death or pushed over the edge by comrades eager to save their own lives. Constantine’s cavalry chopped down those of the enemy that made a stand on the river’s shore while volleys of arrows, stones, and darts showered upon the confused multitude on the bridge.

Alone among Maxentius’s soldiers, the Praetorians valiantly stood their ground. It was the last battle in their 300-year history and they went out in a blaze of glory. Surrounded and outnumbered, the Praetorians fought on well into the night. When the battle finally died down, swaths of slain Praetorians lay at the same spot where they first had taken up formation. Behind them more red carnage covered the river’s banks while heaps of cadavers and broken timbers choked the current.

Constantine Put to Death Maxentius’s Family and Closest Friends

The dramatic end of the Praetorians follows the Panegyrici Latini, our most complete source on the campaign. An alternate version is depicted on the Arch of Constantine: Harassed by Constantine’s heavy cavalry and horse archers, the Praetorians retreat over the pontoon bridge, which breaks under their weight.

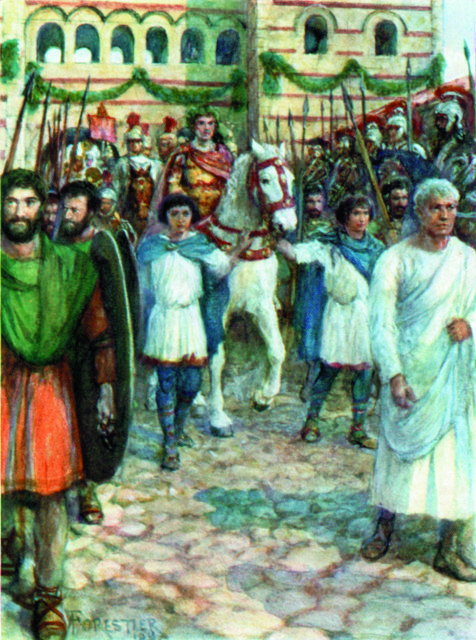

Maxentius’s body was found washed up on the shore. Impaled on a spear, the vanquished emperor’s head served as Constantine’s war trophy when he entered Rome in triumph on October 29. Everywhere the people crowded the streets, hoping to catch a glimpse of the liberator. He was greeted with resounding applause, while the crowd cursed and booed at the sight of Maxentius’s head. Constantine put to death Maxentius’s family and closest friends, but refrained from the wholesale executions demanded by the bloodthirsty Roman mob. Maxentius’s head was sent to Africa as a warning and his name was erased from all public monuments.

The victory at the Milvian Bridge made Constantine sole emperor of the west. Games and festivities were held to appease the crowd, and Senators were restored to their former positions. However, if the Romans thought that Constantine was going to restore Rome to its bygone exalted position, they were gravely mistaken. He turned Maxentius’s “free gifts” into a perpetual tax and even tried to abolish the bloody “circus” games. As for the symbol of “Roman” martial might, the Praetorian Guard, they were disbanded forever. Their barracks were demolished and the few surviving soldiers distributed among the frontier garrisons.

Constantine would not even reside in Rome. After only two or three months, he left in early 313 to meet co-Emperor Licinius at Milan. Constantine returned to Rome only twice during the remaining 24 years of his reign. Of course, in the end he founded the “new” Rome of Constantinople in the east.

At Milan, Licinius applauded Constantine’s victory and further cemented his alliance with his betrothal to Constantine’s sister. More importantly, convinced that his victory was due to the God of the Christians, Constantine persuaded Licinius to adopt a policy of complete religious toleration for all the subjects of the Empire.

The depth of Constantine’s conversion is a matter of debate. Suffice to say he made Constantinople a Christian capital, built numerous churches, and was partial to his Christian advisers. Shortly before his death he banned all sacrifices and finally accepted baptism, although he never submitted to the authority of the Church. At first he did his best to maintain the peace between the Christian and pagan factions in his Empire, but later issued decrees to close down all pagan temples.

Much of this was still in the future. For now there was still the third emperor, Maximinus Daia, a relentless oppressor of the Christians, to deal with in the east. Even after Daia was defeated by Licinius, the remaining two emperors proved one too many. Relations between Constantine and Licinius deteriorated until they thrust the Empire into the final round of the civil war.

By Ludwig Heinrich Dyck / ludwigheinrichdyck.wordpress.com

¹Zosimus, New History. translated by Ronald T. Ridley (Sydney: Australian Association for Byzantine Studies. 1982), p. 29.

Sources

Baker G.P., Constantine the Great. New York. Barnes & Noble Inc. 1967, Bunson Matthew, A Dictionary of the Roman Empire. New York: Oxford University, Cary M. and Scullard H.H., A History of Rome. London: MacMillan Education.1988, Delbruck Hans, The Barbarian Invasions. Trans. R. Walter. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. 1990, Eusebius, Life of Constantine. Trans.Cameron A. and Hall Stuart G. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1999, Gibbon Edward, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Vol.I. London: Methuen & Co. 1909, Goldsworthy, Adrian Keith, The Roman Army at War 100 BC-AD 200. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1998, Lactantius, De Mortibus Persecutorum. Trans. Creed J.L. Oxford: Claredon Press. 1984, Norwich John Julius, Byzantium The Early Centuries. London: Penguin Books.1990, Macdowall Simon, Late Roman Cavalryman. Oxford: Osprey. 1999, Mannix Daniel P. , The Way of the Gladiator. New York: Ibooks Inc. 2001, Mynors. R.A.B., Historical Commentary. In Praise of Later Roman Emperors. The Panegyrici Latini. Trans. Nixon C.E.V. and Rodgers Barbara. S. Los Angeles: University of California Press. 1994,

Rankov Boris, The Preatorian Guard. London: Osprey. 1997, Zosimus, New History. Trans. Ridley Ronald T. Sydney: Australian Association for Byzantine Studies. 1982.