On the roof of Aber Hall dormitory on the campus of the University of Montana, there is a small storage room. Inside, there are crates upon crates of survival supplies for a fallout shelter. Supplied by the Office of Civil Defense of the Department of Defense, each of the boxes contains two large containers of “survival ration biscuits.”

Most of the containers are marked with a packaging date of November or December 1963. They are bygones from an era when the threat of nuclear war was present every day.

Thankfully, the bombs never fell, and the emergency shelters were never needed.

Susanne Caro is the government documents librarian for the UM Mansfield Library. She says, “…we forget that, no, people really did think that this was going to happen. The government spent millions and millions of dollars betting that this was an actual possibility.”

There is a map from the 1970s of the Missoula County’s Community Shelter Plan in Caro’s exhibition in the library called “Duck and Cover! Fact and Fiction of the Nuclear Age.”

The map shows at least 60 fallout shelters in the county. Eighteen of those are on the UM campus. The plan calls for sheltering 4500 people at the Mansfield Library, 3650 in Adams Field House and 1500 in both Aber and Jesse halls.

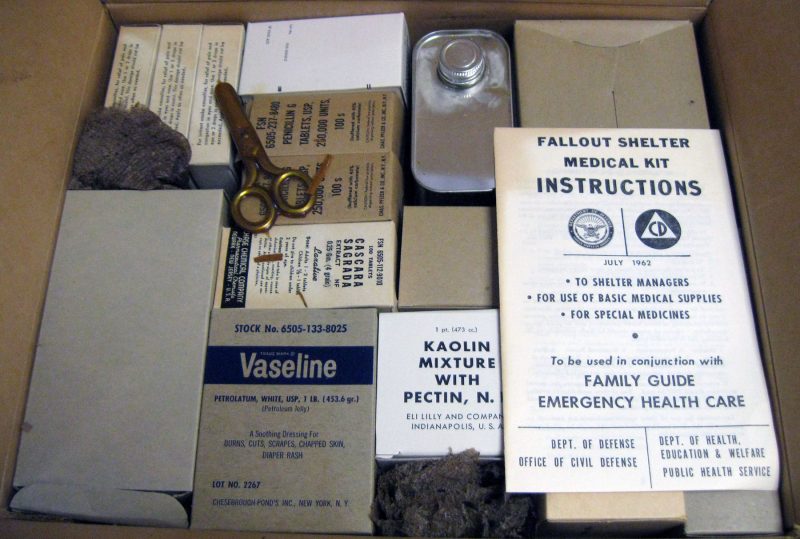

According to Caro, the food supplies consisted of survival biscuits and “carbohydrate supplements” (lemon and cherry drop candies). They were intended to help a person last two weeks on 700 calories a day. Through the years, the shelter supplies have been removed from most shelters.

Ron Brunell can’t figure out why several hundred boxes of supplies would have been stored at Aber Hall in the first place. Brunell worked in and eventually was director of the Residence Life Office from 1970 until his retirement in 2010. “That’s something that never made any sense to me. It seems like a very unlikely place that you’d shelter people in case of emergency.”

Brunell came to UM from Butte as a student in 1967. He had arrived a few months before Aber Hall opened. According to him, the supplies were moved into the rooftop storage room soon after. He was a residence assistant for one summer in Aber. Even though the supplies were off limits, he was still aware of them.

“As I remember there were four different things,” he said. “There were cans of water, what looked like maybe 20-gallon cans. There were hard candies in about 5-gallon cans, and there were boxes of some kind of hard biscuits. And then there were cartons of tissue paper and toilet paper, those kinds of things.”

While he was the director, the paper items were donated to charity because they presented a fire hazard.

It’s time for it all to go now.

Every summer, one residence hall gets shut down for a makeover. This summer is Aber Hall’s turn. Brad Hall, the facilities Manager for Residence Life, said that the supplies will be thrown away if no home can be found for them.

After World War II, the U.S. government recommended citizens build their own fallout shelters.

In the early 60s, culminating in the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, “there was a big push not only for the creation of shelters but the supply of those shelters,” Caro said.

In 1961, the Kennedy administration brought out the National Fallout Shelter Survey and Marking Program. It located existing public fallout shelters and stocked them. It also included plans for citizens to reach the safety of the shelters in an emergency.

“To me, this is kind of a reflection of how little we understood the devastation of radiation,” said Carol Bellin, lecturer. “The fantasy that we can just go into a shelter for a few hours, or days, maybe even weeks, then come out and resume life as normal just shows we were in the infancy of understanding.”

Lt. Ryan Finnegan, the public affairs officer with the Montana National Guard and Montana’s Disaster and Emergency Services, says that there are no more emergency programs on the scale of the fallout shelter program. “The closest thing we have is we do stock up on the MRE – Meals Ready to Eat – program.”

Armories across the state stock up on food in the fall to be distributed in winter emergencies.

“We’re very fortunate these days that the biggest threat we plan for every year is weather and natural disaster rather than during the Cold War with that kind of stuff,” Finnegan said. “That’s what makes this find at the university so interesting. It’s like a time capsule of the way we lived back in that time.”