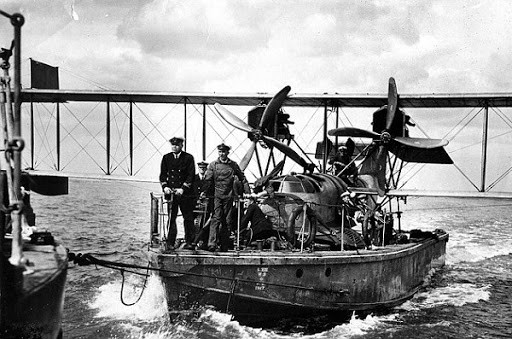

On August 10th 1918, Lieutenant Stuart Culley sat in the cockpit of his Sopwith Camel envisioning the raid upon which he was about to embark. Instead of the soft, green grass of the runway that he would normally have seen from his vantage point, he looked out over 58 feet of wooden runway pitching and rolling against the dark grey of the North Sea. His ‘runway’ was fixed to the deck of a Thorneycroft Seaplane Lighter.

This was the Admiralty’s response to the devastating Zeppelin raids that the Germans had launched against Britain and it was his job to get his Sopwith launched from this perilous location, into the air and destroy Zeppelin L53. His deck crew, whose job it was to hang onto the plane until its engines were run up to full throttle, watched as the little plane shook and the fabric covered wings vibrated as the roar of the engines filled the air.

As soon as Culley gave the signal, they pulled the chocks away from the front of the wheels and watched as he raced over the few feet of deck and staggered into the air. Culley and his plane climbed to 19,000 feet where he found his target and blasted it into a ball of flame that fell into the North Sea. Culley had no means of landing his aircraft so he calmly ditched the little plane and waited for rescue. This raid was so successful that the Zeppelin raids against Britain were stopped in their tracks and Culley was awarded the Distinguished Service Order for his bravery.

The modern aircraft carrier, with almost a kilometre of deck and crews of hundreds of specialists, is a very far cry from the very first aircraft carrier, the Thorneycroft Seaplane Lighter. The lighter was the brainchild of the Admiralty and was the first vessel that was designed to support airborne operations during wartime. The vessel was designed by Thornycroft and many were built by the Royal Engineers based at Richborough, a port built especially for them near Sandwich, Kent. The lighter was designed with a high speed bow, necessary to allow the vessel to be towed fast enough so that the air over the wings of the plane on its deck was sufficient to provide lift. The hulls were galvanised for the first few vessels built but later they were made of steel as cash was tight during the war years.

Two types of lighter were built; the first was designed to carry the Curtiss H12 flying boat and the second was designed to carry the Sopwith Camel. The design for the flying boat included the capability for the lighter to be flooded for the plane to either be disembarked or recovered. Once the seaplane had been recovered, compressed air, stored in bottles, was used to refloat the vessel. For those lighters designed to carry a fighter, an elevated inclined wooden deck was bolted to the vessel and the Sopwith Camel was lashed to this deck. As described already, this was used to launch the fighter into the air. Both designs had a small cabin at the bow end where the deck crew did their best to stay dry and it also provided a storage compartment for tools.

These hardy little vessels played an immensely important role in the defense of Britain in WWI and when the remnants of lighter number H-21 were found by a maritime journalist who recognized the hull that was sticking out of the mud on the banks of the Thames, historians were determined to save her. The journalist passed on news of his discovery to Graham Mottram, the director of the Fleet Air Arm Museum in Somerset, who immediately visited the site and made arrangements for the remains of this vessel to be transported to the museum for restoration. He told an interview with the BBC:

“I was well aware of the story of these seaplane lighters, but was astonished to find that one had survived intact. My short walk along the deck was some of the most exciting steps I have ever taken!”

In 1996 the wreck was moved to the Fleet Air Arm Museum at Yeovilton and as a restoration of this nature is hugely expensive in terms of both manpower and budget, it has progressed slowly. In 2008, the museum made plans to build a new hall that would feature H-21 with a plane in place. This gave a boost to the restoration plans and by 2009 restoration was in progress with careful attention being paid to ensure all her details were absolutely correct. Original plans from Thornycroft were sourced and where her fittings could not be restored they were meticulously crafted from the original specifications.

The restoration work has taken a long time but has revealed the symbol of the War Department, a broad arrow, and the details required by the Ministry of Defence such as its length (LVIII or 58 feet) and the original boat number, H-21. Dave Morris, the curator of aircraft at the museum, said:

“The boat came to us after it was spotted on the banks of the Thames. It was actually in remarkable condition. We have stripped back the Thames barge paint that covered it and returned it to its original WWI condition. It’s incredible to compare it to today’s aircraft carriers but this is where it all started.

“It is one of the great First World War pieces still in existence and among just a few original large objects remaining.”

Once restored this vessel will be on display with a Sopwith Camel lashed on the deck, as though ready to take to the sea once again in defense of the realm.