During WWII, the Philippines was one of the few countries that accepted Jews. And while the swastika meant eventual death for Jews in Europe, it ended up saving them in their new home.

Jews had been in the Philippines since the 16th century, but it was only with the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 that their numbers grew. When the US took over in 1898, their numbers grew even further.

Then the Nazis took over Germany in 1933. The first German Jews arrived in Manila (the capital) in 1935, but most preferred Shanghai, China which hosted about 18,000 Jews. At least till 1937 when Germany became allies with Japan.

Since Japan invaded China, it was feared that the Japanese would adopt anti-Semitic policies. To deal with this, the Jewish Refugee Committee of Manila was created to repatriate the Jews of Shanghai to Manila.

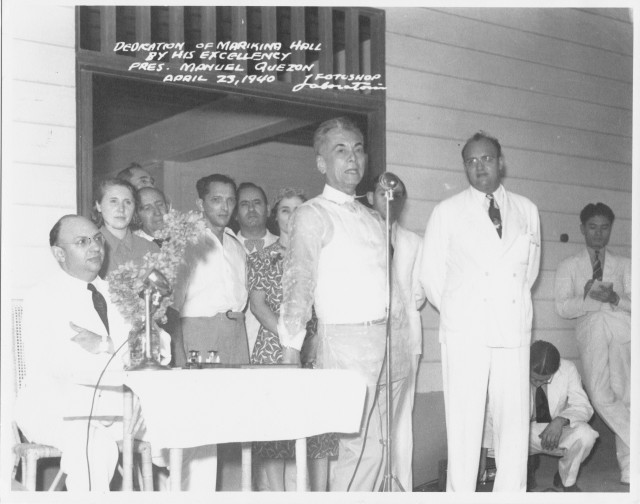

Their work increased in 1938 when Germany annexed Austria and an influx of Austrian Jews began arriving that same year. These events would lead to the Open Door policy under President Manuel Quezon.

Since the Philippines was still American property, however, Quezon’s ability to dictate the country’s immigration policy was extremely limited. Fortunately, Jewish economic influence in the Philippines was considerable enough that the US government couldn’t ignore it.

America knew how Jews were being treated by the Nazis, but it was a strictly neutral country at the time. The US government was therefore reluctant to accept German and Austrian Jews for fear of creating tensions with Germany.

The Philippines, however, was another matter entirely.

Although a Spanish colony since 1570 and predominantly Catholic, anti-Semitism was an alien concept to the indigenous Filipinos. Often subjected to extreme racism under Spanish rule, a number sympathized with the Jewish plight. There was also the fact that most did not (and still don’t) understand the difference between a Caucasian who was a Christian and another who was a Jew.

On 9 November 1938, Kristallnacht broke out in Germany – an attack on Jews and their establishments. Though internationally condemned, few countries offered to take in the Jews. In Manila, however, over a thousand rallied to condemn Germany and calls were made to offer refuge to them.

On December 5, Quezon made a public announcement offering asylum to as many as the country could take. Those already in Manila began contacting relatives in Europe. Some even sent job offers, which allowed those already in concentration camps to get out.

But it was not enough. There was also the question of politics and cost.

Since the Philippines was represented overseas by US consular offices, High Commissioner Paul McNutt agreed to issue visas to Jews in Germany and Austria. The US State Department ordered a cap, however, since America wasn’t exactly pro-Jewish back then. So that covered the politics.

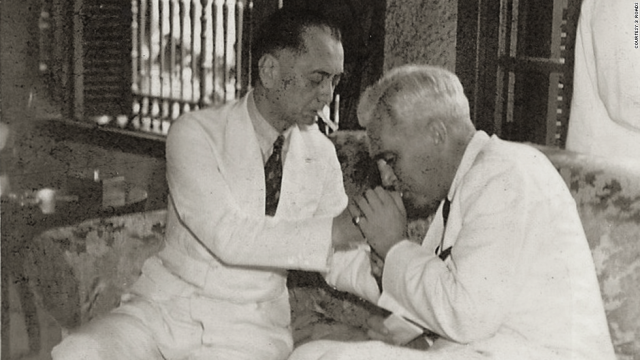

For finance, there was the Frieder brothers. Morris, Herbert Philip, Henry, and Alex were American Jews who became tobacco barons in the Philippines and were part of the country’s political landscape.

Being Americans, the Frieders also had clout with the US government. With approval from Quezon and President Roosevelt, as well as other prominent Jewish families, they formulated a plan to repatriate thousands of Jews to the Philippines.

A list of 12 needed professions were drawn up. If a Jew qualified for any of these, they and their entire family were guaranteed a Filipino visa.

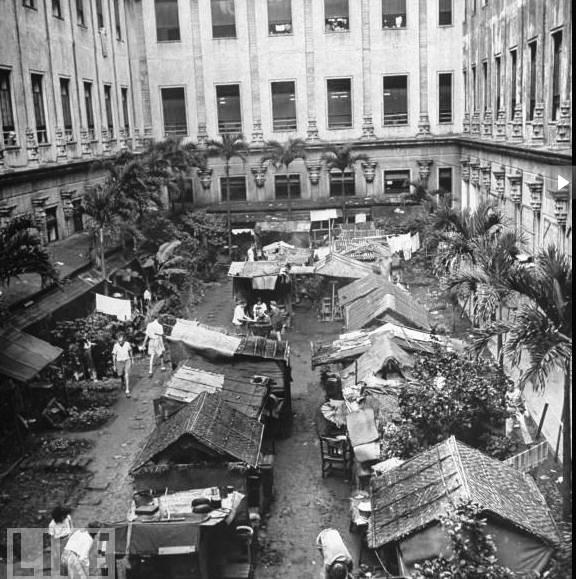

The local Jewish community had offered homes and jobs to the refugees, but as word spread throughout Europe and the number of arrivals grew, they were quickly overwhelmed.

Quezon, who came from an old Filipino-Spanish dynasty, offered a portion of his Marikina estate (now a district of Manila) to the final wave of arrivals. Comprising 21.52 km2, even that wasn’t enough.

It was therefore decided that the island of Mindanao could take in an additional 10,000 Jews. The plan was that these would create the infrastructure to take in more. With approval from the US State Department, the Philippines officially opened its doors to receive the influx.

Then the Japanese invaded on 8 December 1941 – a mere ten hours after they had attacked Pearl Harbor.

Americans soldiers were sent on a death march to Bataan. Others deemed to be enemy aliens were sent to concentration camps throughout Manila and in neighboring districts.

Nor were Filipinos safe. The Japanese Army took food and other resources, seized houses and businesses. Women and girls were turned into “comfort women” – sex slaves for the military. Beatings and summary executions were also common. By the time their occupation ended in 1945, it’s estimated that over a million in Manila alone had died, many from hunger.

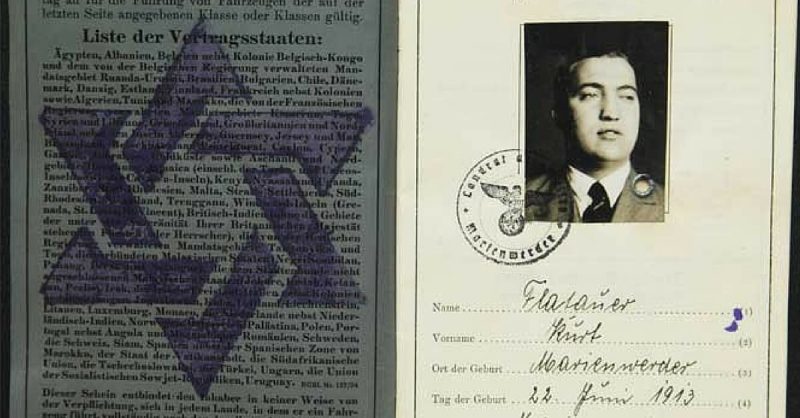

But the German and Austrian Jews were safe. The former had kept their passports which had swastikas on them. The latter were native German speakers, so they were considered to be German citizens.

Although Germany did ask Japan to adopt anti-Semitic policies, most Japanese had no idea what a Jew was or actually cared. As far as the Japanese were concerned, they had an alliance with Germany – and if a European spoke German, then they had to be German.

Foreign nationals of interest, including a number of American and British Jews, were interred at the University of Santo Tomas. Though not killed outright, the Japanese couldn’t be bothered to feed them, so roles became reversed – German and Austrian Jews did what they could to feed them.

Nor did the Japanese give up the Philippines easily in 1945. Knowing defeat was inevitable, they went on a killing spree and destroyed what they could. Prior to 1941, the Philippines was one of the largest exporters of sugar, hemp, and tobacco – making its economy second only to Japan. But it never recovered after the war.

It’s estimated that between 1,200 and 1,300 mostly German and Austrian Jews made it to Manila before the Japanese invasion, while 67 died during the occupation.

In 2009 the Israeli city of Rishon LeZion set up the Open Doors monument to commemorate the refuge the Philippines provided.