The promontory of Montfaucon was at the center of the German line in the Meuse-Argonne offensive. On the morning of September 27, 1918, the Germans holding the hill found themselves outflanked by the American 37th Division to the west and the 4th Division to the east and threatened by the 79th Division in front. Army Group Commander General Max von Gallwitz ordered a withdrawal and the American 313th Infantry Regiment, part of the 79th, entered the town.

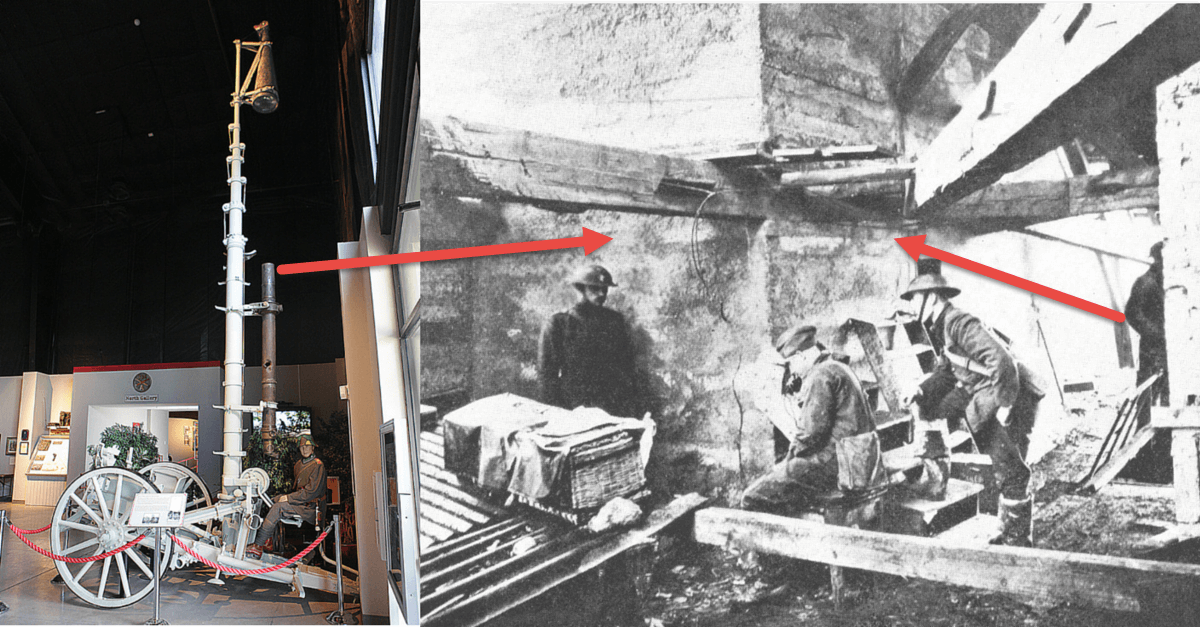

As the men of the 313th consolidated their position they discovered many observation posts and defensive positions dug into the sides of the hill—eventually more than a hundred, some constructed from old wine cellars and the basements of ancient ruins. One of the observation posts was exceptional: Inside a large, three-story building on the west slope stood a tower with thick, reinforced-concrete walls extending from the basement to the roof. On the first floor was a carriage-mounted periscope whose telescoping pole was extended to the roof, a height of 35 feet (the full height of the pole was 85 feet). Under the roof was a chart room with a map of the surrounding countryside and a scale marked off in mils of deflection so that the periscope could quickly be aimed at any desired point. Observers could view a target from the ground floor through eyepieces or from other floors using a system of mirrors and prisms. The equipment was in working order except that, in the words of the historian of the 79th Division, “Before it could be brought to bear on the enemy lines, some thoughtless souvenir hunter stole the eyepieces, rendering it useless.”

The first phase of the offensive was still under way so the 79th quickly advanced beyond the town, chasing the retreating Germans. But it left behind a squad from the Headquarters Company to operate the observation post. For three days a sergeant and two privates manned the position – although not the periscope—under heavy fire; for this they were later awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.

On September 30 the exhausted 79th was relieved and the veteran 3rd Division, the Rock of the Marne, moved in. They found the periscope in place, dismounted it—it took four-and-a half days—and sent it to III Corps on October 30. They reported that it was “in excellent condition except that some of the hoisting cables were broken, the telescopic eye-pieces smashed [hadn’t they been stolen?], and one section of the elevating pole dented by shrapnel.” In February 1919 the periscope was shipped from the French port of St. Nazaire directly to the United States Military Academy at West Point.

The periscope and the building in which it had stood quickly became known as the “Crown Prince’s Observatory” from which he was said to have directed the Battle of Verdun in 1916. Who among the Americans first made this attribution is not known. It is unlikely that the Crown Prince “directed” the battle from that position, or that the periscope was intended for such a purpose, as it was more than 20 kilometers west of the main action and the building in which it was housed was on the far slope of Montfaucon and below the crest. The observatory’s purpose was clearly to survey the south and southwest to guard against a French attack from those directions. It is certain that German Crown Prince Wilhelm, who commanded that portion of the German line from 1914 to the end of the war, used it for that purpose. As he wrote in his memoirs, “On December 29th [1915, before the attack on Verdun] I was inspecting the front of the 6th Reserve Corps from the observatory of Montfaucon, and from this magnificent view-point my eyes first sought out, not the Argonne forest at my feet, as they had been wont to do hitherto, but the eastern bank of the Meuse, where, behind the hills of Horgne, Morimont and Komagne [sic], such fateful matters were in preparation [emphasis added].”

Soon after its arrival at West Point the periscope became the subject of a minor controversy. In his transmittal letter Major General Robert Howze, commander of the 3rd Division, requested that it be labeled, “Captured by the units of the Third Division.” Brigadier General Douglas MacArthur, then superintendent of the Academy, sensed trouble and forwarded Howze’s letter to Major General Joseph Kuhn, former commander of the 79th, requesting that he work out the matter with Howze so that a properly worded plaque could be affixed to the object. In the meantime, other former officers of the 79th got wind of the proposed attribution, which they regarded as “clearly an injustice to our dead who helped take the town.” The upshot was that the plaque was worded to read, “Montfaucon captured by 313th Regiment, 79th Division, September 27, 1918. Periscope dismounted by 3rd Division and presented by it to the Military Academy.”

The periscope quickly became a prominent and celebrated trophy at West Point. Graduates and their families were photographed in front of it. Newspapers and magazines printed its image. But with the advent of World War II, the previous war and its memorabilia fell into the shadows; the periscope was relegated to the West Point Museum and in 1967 it was transferred to the National Armed Forces Museum Advisory Board. But NAFMAB disbanded soon thereafter without cataloging all of its acquisitions, so the location of the periscope became a mystery.

Inquiries to the Army Historical Foundation, the Center of Military History, and the Smithsonian Institution yielded the suggestion that it might be in the U.S. Army Field Artillery Museum at Fort Sill, Oklahoma. In 1999 the museum’s director wrote that the item had been in the collection for many years “and yours is the first inquiry I have received about it.” It was not clear, however, that the Museum staff understood the history of the piece; it was identified only as a German fire-control periscope. But in a recent exchange the current curator of the Artillery Museum, Gordon Blaker, confirmed that the item is now exhibited in the main gallery and, after reading the documentation, acknowledged that it is the periscope captured on Montfaucon.

One hopes that the object will be properly identified on its label, so that visitors may appreciate what was once the very embodiment of the American achievement in World War I.

By Gene Fax for War History Online

Gene Fax is an engineering graduate of MIT and co-founder and chairman of The Cadmus Group, Inc., a consultancy in environment and energy policy studies. Early in his career he conducted research and tactical studies in anti-submarine warfare for the U.S. Navy. He is writing a book on the 79th Division at Montfaucon.

Images credits:

1&2: Frank J. Barber, History of the 304th Engineers, 79th Division, USA, in the World War 1917-1919, Steinman & Foltz, 1920

3: U.S. Army Artillery Museum