“I believe that the nation as such should be annihilated, or, if this is not possible by tactical measures, expelled from the country. The Herero people will have to leave the country. If the people refuse I will force them with cannons to do so. Within the German boundaries, every Herero, with or without firearms, with or without cattle, will be shot. I won’t accommodate women and children anymore. I shall drive them back to their people or I shall give the order to shoot at them.” This was the instruction given by General Lothar von Trotha in 1904 which began the genocide against the Herero people.

The Herero people, a peaceful, nomadic, cattle-herding tribe living in what was then South-West Africa, and now known as Namibia, were an extremely wealthy tribe and their cattle foraged over a third of the country. They had been successful in keeping the German colonialist expansion at bay but they, along with the Nama people, had been pushed into open rebellion and von Trotha had been sent to quell the rebellion.

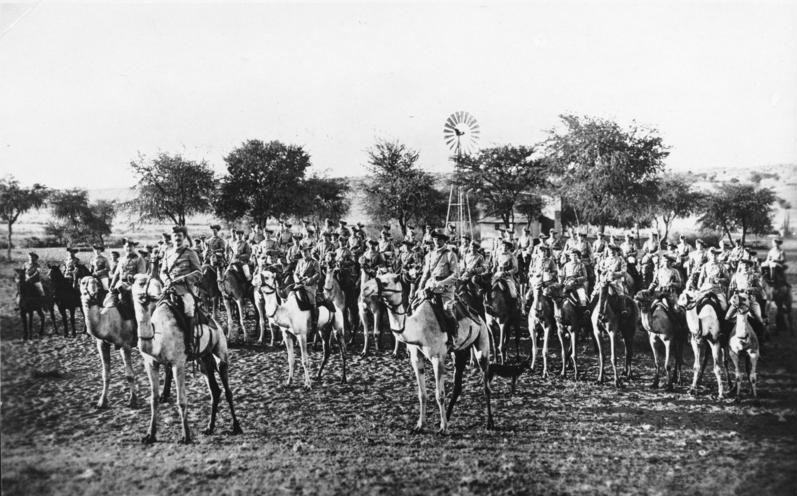

The Herero, as with most tribes in Southern Africa, were armed with very few firearms along with bows and arrows and spears. The Germans with their superior firepower slaughtered thousands, and those that were not killed were driven into the desert, whilst the German troops formed a blockade to stop them returning to their ancestral lands. Their wells were poisoned, and those that tried to break through the blockade were bayoneted.

In an eerie premonition of another genocide that was to occur some forty years later those Herero that managed to survive the crippling thirst were pushed into concentration camps and were impelled to dig up Herero graves to collect the interred skulls. The women were forced to clean the skulls by boiling so that the Germans could conduct experiments to prove Aryan superiority over the African race. It is estimated that 110,000 Herero and Nama people were slaughtered.

Today the Herero make up some 10% of Namibia’s population, living in desolate conditions and struggling with many social ills including unemployment and alcohol and drug abuse.

Twelve years ago in 2004, Heidemarie Wieczorek-Zeul, Germany’s Development Minister, visited Namibia and publically acknowledged the fact that the massacre perpetrated in 1904 did constitute genocide, but it would take another ten years for this to form a formal part of German-Namibian relations. At the same time, the skulls stolen in 1904 were returned. Naturally, the Herero were very pleased to have the remains of their ancestors returned to their homeland, but there were naturally still furiously angry over the fact that the genocide was still unacknowledged.

Now in a milestone event, German Chancellor Angela Markel, said, in a statement, that her country would formally recognize and apologize for the systematic murder of Namibia’s Herero people more than a century ago. A spokeswoman for the German Foreign Ministry, Sawsan Chebli, said on 13th July 2014, “The federal government has been pursuing a dialogue with Namibia on this very painful history of the colonial era since 2012. We seek a common policy statement on the following elements: a common language on the historical events and a German apology and its acceptance by Namibia.” Germany was adamant, however, that there would be no compensation paid; instead, Germany would contribute to development aid for Namibia.