By the close of the second century B.C., the Roman Republic was unarguably the supreme military and political power in the Mediterranean world. Its influence stretched from the straits of Gibraltar in the west, to Suez in the east. Despite this dominance and the subjugation of former powers like Athens, Macedon, Carthage, and Egypt, the period was not without its threats and exceptional military leaders were still called for. The two greatest of these were Gaius Marius and Lucius Cornelius Sulla.

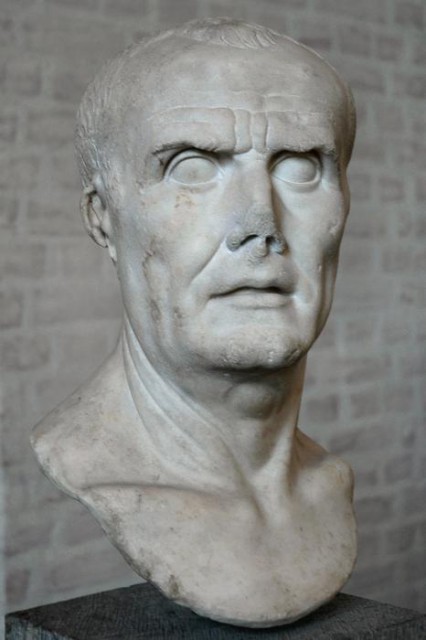

Marius, an Italian by birth rather than a pure Roman, was a relative newcomer to the Roman elite, and he was considered an outsider by the Senate fathers. It was not until he was in his very late forties and almost past the age of command that he took sole charge of a major war, in this case subduing the renegade king of Numidia, Jugurtha. Even this relatively undistinguished placement was only attained in the face of the sternest opposition of senators representing the old patrician families of Rome.

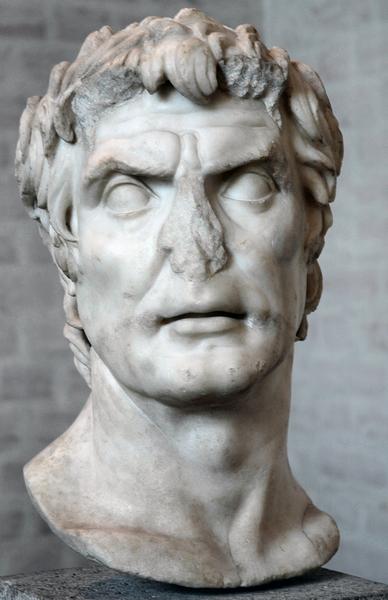

Sulla, then aged about 30 and a late starter himself, was brought into Marius’s inner circle by his marriage to the younger daughter of Gaius Julius Caesar, grandfather of the much better known Julius the Dictator. Marius had married Caesar’s elder daughter, making him and Sulla brothers in Roman law. These marriages had served them well; Marius gained an entrance into the highest noble circles and Sulla gained a return to patrician status following the squandering of his inheritance by his alcoholic father. Both men clearly had a lot to prove in the coming wars.

The campaign against Jugurtha proved difficult, as the Numidian had served Rome as an auxiliary in his younger years and was familiar with their tactics, but it was ultimately successful. Sulla personally captured the desert chieftain in a daring raid and brought him back to Marius’s camp in chains.

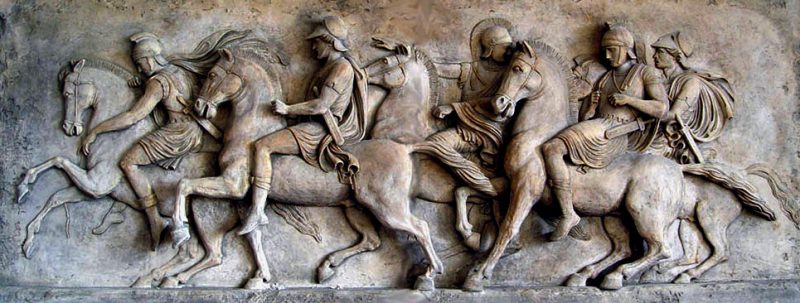

Following his triumph, Marius, with Sulla again as his military tribune, marched north to confront the much more serious threat of the German tribes, several of whom were making ominous movements in the north and had already devastated Roman armies sent to force them back; the casualties from the Battle of Arausio were said to eclipse even those that Hannibal had inflicted at Cannae and the senate and people of Rome were desperately in need of an able commander. In Marius and Sulla, they gained two.

The war with the Germans was concluded with two tremendous battles at Aqua Sextiae (102 B.C.) and Vercallae (101 B.C.). The Romans captured and enslaved over 80,000 people following these two encounters, giving some historically viable idea of the scope and size of the wars themselves. By this time, Marius had introduced so many changes to the Roman legions that they were almost unrecognizable to the armies that had vanquished Carthage less than fifty years before. In his early campaigns, he had modified both the Roman pila throwing spear and the common infantryman’s shield, squaring it so that the legionaries could march comfortably with it on their backs. Next he introduced a law that was tantamount to sacrilege in the eyes of the noble senators.

The Republic was so starved of men from its endless wars and battles (the defeat at Arausio was said by Livy to have cost the lives of 100,000 Romans and Italian allies) that land owning citizens of the correct age were becoming hard to come by. Many of the men already in the legions found that their enlistments were being arbitrarily extended into longer and longer terms of service as the manpower pool back in Italy dried up. To counter this, Marius had begun enlisting men from what was known as the “head count”, the common men without property or the means to equip themselves with weapons. The senate vigorously resisted this at first, but finding itself pressed by the demands of their foreign commitments, they eventually found it expedient.

One of the unforeseen circumstances of the change was that the legions were now paid rather than volunteers – a professional army. The soldiers signed up for a period of 16, later extended to 20, years and when their time came to an end they were given a bonus and a plot of land to work in retirement. Their generals, whom they now served for long periods of time could also reward them with bonuses as spoils of war. The end result was that the first loyalty of the legionaries was no longer the Roman state, but to the generals that they served under.

Marius effectively retired from active service following the German wars, but Sulla remained very much at the forefront of national and military affairs, and when a new enemy arose in the east, Mithridates of Pontus, his fellow nobles and other admirers in the senate gave him the command of an army to lead against the menace. Sulla was enticed not only from the prospect of the riches of the region, but also as a result of Mithridates’s slaughter of tens of thousands of Roman and Italian merchants in the republic’s province of “Asia”, now western Turkey.

Marius had also campaigned for the appointment, and he took advantage of some political infighting in Rome to have the command transferred to him whilst Sulla was out of the city. Indeed, Sulla was in the south of the country preparing to embark for Greece when he received news of his demotion. He refused to accept the senate’s decision and marched north to Rome. The bonds between the two former fast friends were irreversibly severed.

The impact of Sulla’s first march on Rome at the head of a Roman army is hard to adequately quantify. Never before in the city’s seven centuries of existence had one of its own armies attacked it. Contemporary sources say that only one of Sulla’s officers agreed to march with him. Ironically, Sulla was only able to mount such an attack as a direct result of Marius’s own reforms of the Roman Army. The six legions he led were steadfastly loyal to him alone after serving with him during the recent Social War, an uprising of Italian cities against the high handed hegemony of Rome. Marius could not match these forces with the few street thugs and armed gladiators he could call on in Rome, and he and some of his supporters retreated from the city before Sulla arrived.

Once he took control of the capital, Sulla declared Marius and his political supporters outlaws against the state, stamping his authority on the senate and government and ensuring, at least to his satisfaction, that the situation was now under control. With Rome under his command, he moved south again and then embarked to fight the war in the east, first in Greece and then in Asia.

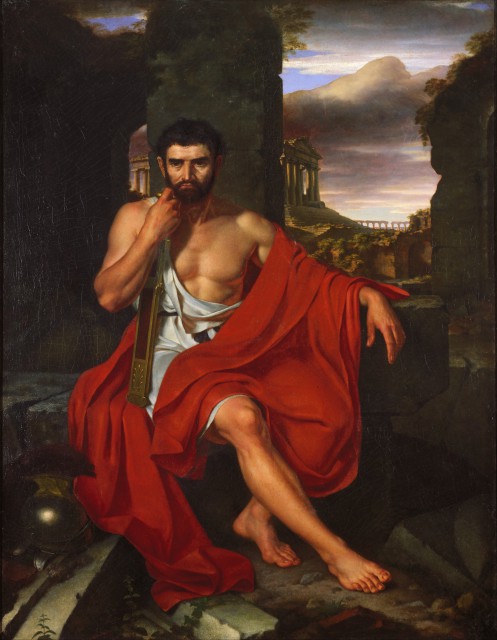

While Sulla was busy avenging the attacks on the republic, Marius re-emerged in Africa, where he raised a token force and then sailed for Rome, overpowering the forces that Sulla had left in place. Along with his ally, Lucius Cornelius Cinna, Marius attacked and killed Sullan supporters without trial. Now seventy and rumored to be completely mad, he then made himself consul, with Cinna as his counterpart, thus holding the office for a record seventh time. He had just enough time to declare Sulla an outlaw in turn before he died, raving, just a fortnight later. On hearing of the debacle back in Rome, Sulla patched up a peace with Mithridates and marched on the city once more, but he arrived too late to deal personally with the man who once been his closest ally. This time, however, Sulla was indiscriminate with the executions of Marian supporters and Cinna, Marius’s last ally, was killed in a degrading brawl with his own soldiers.

The rivalry between Sulla and Marius had begun as a competition to see who could win the greater glory, or dignitas in the Roman lexicon – prestige or fortune in the eyes of their fellow citizens. Unfortunately, the timing and the personalities of the two men meant that not only were their own lives forever altered by their vendetta, but the precedent had been set for other Romans to follow their example. The Republic that had been built on the twin foundations of discipline and unwavering tradition was never the same again.