The British army at the outbreak of World War 1 was made up of men who wanted a life in the military and they marched off to fight when asked by their Government. However, towards the end of 1915, things were not going well for the British forces, with a near deadlock situation on the Western Front and the Gallipoli campaign an unmitigated failure. The only means of rapidly gaining more men to fight was to introduce conscription, which the Government did by promulgating the Military Service Act, which came into being on the 2nd March 1916.

All able-bodied men were expected to report for service but the Government had little idea how to deal with those men who chose, by virtue of their belief systems, not to fight; the conscientious objectors or, as they were colloquially known, ‘conchies’.

If you did not want to fight you could appeal against military service and your case would be heard by a tribunal made up of local, prominent, middle-class persons who would decide if your case constituted ‘conscience or cowardice’. The objector was required to provide proof of his objection, often a nearly impossible task as one’s belief systems rarely have inviolate proof to offer a court of law. The evidence rules within the tribunal were very lax as compared to a court of law and hearsay and personal opinions were permitted. The reasons put forward for not wanting to fight most often were based upon religious grounds or political beliefs. In addition, the depth of the objections also varied enormously; some were prepared to act in a non-combative role such as a medic or stretcher bearer whilst others objected to any form of conscription. The tribunals were extremely unsympathetic to these men and from March 1916 to the end of the war only 16,000 men were registered as legitimate conscientious objectors out of some 750,000 cases brought before the tribunals.

Opposition to the war was a very unpopular view and the conscientious objector made up 0.5 per cent of the able-bodied male population but campaigns were run to heap shame on those who chose not to fight. White feathers were presented to conscientious objectors. Anyone who was not in uniform and was seen to be ‘not doing his bit’ for the country.

Of the men applying to the tribunals, there were 1,350 who were determined to gain absolute exemption from military service and of these 985 refused to recognise the tribunals or the military orders dispatched to them as non-combatants. These men were subject to courts martial and imprisonment with hard labour. Many allegations of inhuman treatment against these men were documented – hard labour involved physical as well a mental hardship.

A group of conscientious objectors, known as the Richmond Sixteen, were made up of Quakers, Methodists, Jehovah’s Witnesses and members of the Churches of Christ. They had been granted conscientious objector status and had been designated as non-combatants but they ignored notices to report for non-combat duties and refused to have anything to do with the war effort. This resulted in their arrest by the police and they appeared at the local magistrate’s court. They were handed over to the military police and taken to Richmond Castle. They all refused to undertake any duties nor would they wear a uniform so they were incarcerated in eight small cells pending courts martial.

A decision was taken by the War Office to have four groups of conscientious objectors sent to the Western Front where they could be court-martialled for refusing to obey orders and executed. The Richmond Sixteen, along with another 26 men from Harwich, Kinmel Park, and Seaford were loaded onto trains destined for the Western Front. Whilst on the train, the Richmond Sixteen wrote a letter addressed to Arnold Rowntree, the MP for York, describing what was happening to them and threw it out of a window, hoping it would reach Rowntree. The letter was received by Rowntree who took it to Asquith, the British Prime Minister.

When the Richmond Sixteen arrived in France they were transferred from one place to another until they eventually arrived at Boulogne. At Boulogne, they were told that they were now in the presence of the enemy and failure to obey orders would mean they could be shot as deserters. They were pressed to take on a non-combatant role as not doing so amounted to suicide. They refused to be pressured into accepting orders in the non-combatant environment and were given twenty-four hours to decided whether to accept the army’s orders or not. Of the sixteen, only one buckled under the pressure and agreed to accept orders. The others maintained their conviction that it was morally corrupt to fight and they were all sentenced to be shot on the 14th June but this sentence was commuted to 10 years hard labour instead.

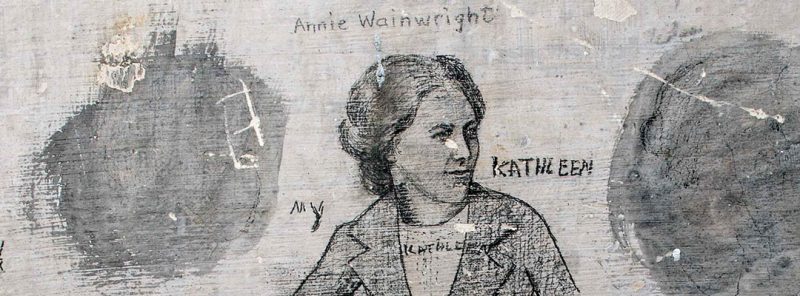

Whilst incarcerated at Richmond Castle these sixteen men used pencils to draw graffiti on the walls of their cells. There are hundreds of drawings, political slogans, poems, hymns and portraits of their families inscribed on the walls. English Heritage is to make every effort to preserve this piece of English history and as part of a £365,400 project these 19th Century cells with their precious graffiti will be preserved.

Rain had seeped through the roof and had threatened to crumble the plaster on the walls to dust thus destroying these precious works of art. The Heritage Lottery Fund will provide the money to repair the cracks and dry out the cells, preserving the artwork. Chief Executive of English heritage, Kate Mavor, said: “These graffiti are an important record of the voices of dissent during the First World War. It is remarkable that these delicate drawings and writings have survived for 100 years. Now we can ensure that they survive for the next century and that the stories they tell are not lost.”

Marjorie Gaudie , the daughter-in-law of Norman Gaudie, one of the Richmond Sixteen, told an interview with The Express, “He acted from the deepest conviction that all life is sacred. He knew it was wrong to take a life and so he refused to fight. He was prepared to die for his belief.”

The importance of the stand taken by these men cannot be underestimated. They paved the way for conscientious objection to be accepted as a legitimate defence against conscription into the military. Ms. Gaudie said, “He and the others paved the way for conscientious objection to be able to come into force, for it to be legal. Although even in the Second World War men had problems and were put into prison, it was more acceptable because of the stand he took. He must have been amazingly courageous to take that stand.”

The cells will be opened to the public when the restoration work is complete.