While Cinco de Mayo today is known to many in the U.S. as a day for drinking, the history of the holiday goes back to 19th century Mexico and the aftermath of the U.S. Civil War.

According to David E. Hayes-Bautista, Director of the Center for the Study of Latino Health and Culture and the School of Medicine at UCLA, the holiday is not the “Mexican 4th of July” many Americans take it for. “Cinco de Mayo is part of the Latino experience of the American Civil War,” he says. “It’s not about the Mexican experience.”

Mexico was under enormous debt to France in the early 1860s. As a result, Napoleon sent troops to conquer Mexico City and form a country that would be friendly to the Confederate states. “The French army was about four days from Mexico City when they had to go through the town of Puebla, and as it happened, they didn’t make it,” Hayes-Bautista says. The smaller Mexican army was able to hold off the better-equipped French army in the Battle of Puebla on May 5, 1862. The next year the French came back and won, but that doesn’t diminish the accomplishment of the Mexicans in this battle.

The Latinos living in California didn’t hear of the victory until May 27. The news was well-received by that group for a couple reasons. First, they were happy to hear of the Mexican victory and second, since California was a free state, they were glad to receive news that French had failed to assist the Confederacy. Hispanics were especially opposed to the South.

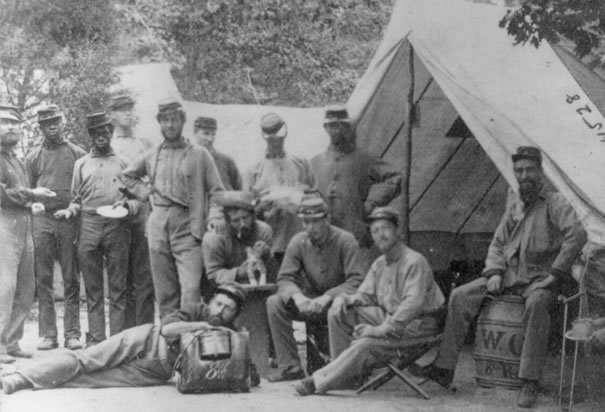

As an example, Hayes-Bautista tells the story of Major Jose Ramon Pico. He organized Spanish-speaking cavalries to fight with the Union army in the Civil War. “His grandmother was listed as mulatto in the 1790 census,” he says. “He came from an African-Mexican family, so he organized troops to fight for freedom and [linked] the Civil War to the French intervention in Mexico.”

“By the time [Latinos in California] heard about the news of the battle, they began to raise money for the Mexican troops and they formed a really important network of patriotic organizations,” says Jose Alamillo, a professor of Chicano studies at California State University Channel Islands. “They had to kind of make the case for fighting for freedom and democracy and they were able to link the struggle of Mexico to the struggle of the Civil War, so there were simultaneous fights for democracy.”

The party atmosphere of the holiday didn’t come until much later. “The 1970s and ’80s really is when the U.S. beer companies began to kind of look for ways to target the Spanish-speaking population,” Alamillo says. It’s the unique nature of the way the holiday is celebrated that maintains its origins. Alamillo was born in Zacatecas, Mexico but didn’t hear about the holiday until he moved to the U.S. when he was 8 years old. He says, “I thought, ‘Why would I hear about it in a classroom in the U.S., but my parents and uncles never heard about it in their schooling in Mexico?’ It’s not a Mexican holiday, not an American holiday, but an American-Mexican holiday.”