There’s not many things technology can’t help us do these days.

We can communicate live across continents in a matter of seconds. We’re able to carry around computers with Internet access in our pockets. Not to mention that anyone can order a pizza in under five minutes, without even having to speak to anyone beforehand.

Looks like the future has arrived, folks.

But aside from all of these obvious perks, there are more and more tools becoming available to us that are helping to reconfigure what was once thought to be lost from the past. Digital technology can seemingly recreate and redesign almost anything we want to rebuild.

And Huw Thomas, an associate professor of industrial design at the University of Kansas, didn’t take this opportunity for granted. He decided to mix his passions and create something amazingly unique – a 3D replica of an engine needed to reconstruct an essential piece of a WWI plane. Yeah, sounds crazy, right? Again, apparently anything is possible if the right people and the right technology come together.

When volunteers at the Topeka Combat Air Museum were in need of some spare parts to recreate an authentic replica of a WWI aircraft, the idea seemed nearly impossible, even laughable at best. Sure, perhaps someone could do their best with some lightweight plastic pieces and some super glue, but it in no way would it appear like an original piece of a once-majestic fighter plane.

In earlier years, Gene Howerter, one of the volunteers in question, would simply throw together pieces of rope, metal, wood, spray paint – and yes, Elmer’s glue – to replicate any of the plane’s missing engine parts that would otherwise go unfinished. The museum needed to acquire something suitable for the masses, that wouldn’t make visitors groan at the lackluster attempt to recreate the original plane.

Howerter had certainly done his best for many years. He had constructed some engine replicas that seemed so life-like, he’d overheard murmurs about how authentic it looked. The plane he worked on had been hung from the rafters of the museum, and he felt pride in hearing positive remarks regarding its realistic appearance.

But about a year ago, the museum had collected a replica that was only 80% completed. The aircraft, a De Havilland 2 WWI fighter plane, had a rear-mounted engine missing. So naturally, the museum looked to Howerter’s fine craftsmanship for help in recreating it. Though Howerter would otherwise be interested, his age had begun creeping up on him. At 75-years-old, he felt the project would be too strenuous to complete by himself.

But before the project could be shut down, in walked Thomas, ready to come to the rescue for the museum. And he had some more modern technology under his belt to help him rebuild along the way, as well.

The Wales native decided that instead of trying to reconstruct the engine for the De Havilland with assorted, repurposed parts, he would try out an entirely new method that the museum had never seen: using 3-D printers. With three printers in total hard at work, he figured he would complete the Gnome rotary engine to near-perfect accuracy for the vintage plane.

And so Thomas set out to do just that. Re-creating dozens of both large and small parts, the finished product would be a work of art in itself, formed by layer upon layer of fine materials and arranged by technology’s best new toy.

The 3-D printers were able to fashion together spare parts out of material with a likeness to Lego pieces, that would then be bonded by an adhesive similar to super glue. The finished replica rotary engine measured out to about three feet across and 14 inches wide, and thankfully only weighed a little more than a few pounds. Once it was ready to position, the engine was adorned with a resin propeller and was finally attached to the back of the de Havilland 2 aircraft. The plane was finally completed, looking like a 100% authentic WWI aircraft.

Now in its proper form, the plane was suspended from the rafters with the other replica planes in the museum’s main hangar at the Topeka Regional Airport, where visitors can catch a glimpse of what would appear to be authentic, original machinery.

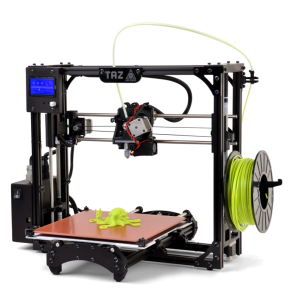

Thomas, for all of his hard work and brilliant imagination, actually completed the project free of charge, though the museum agreed to pay for all of the required materials he needed at his disposal. The two 3-D machines he used for the project were LulzBot TAZ 5 printers that were available at KU. However, once Thomas realized the extent of the time and effort the printing would require, he actually purchased one for himself and worked from home to finish the replica engine.

Thomas stated that it took about 400 hours of printing time to get all of the pieces he needed for the engine, as each of the nine cylinders was made as two halves, coming in at around 14 hours of printing per cylinder. He claimed it took 60 hours to simply design the computer model, a fact that makes Thomas’s decision to not receive payment for his trouble meant all the work was even more noble.

Locating an old copy of the engine’s 1915 service manual also proved difficult, but Thomas managed to find one to help design the newest replica with the same 80% scale of the rest of the plane. He has now also signed on to make a 3-D replica of the Lewis machine gun, to attach on the front of the De Havilland where it would’ve been used by the pilot in the air, fired from the cockpit.

Starting the project in November 2015, Thomas managed to have the replica rotary engine completed by mid-April 2016. He made it just in time to be displayed for visitors coming from all over America to view the detailed design work and craftsmanship of the authentic WWI fighter planes, as well as its newly-acquired spare parts.

Suspended from the rafters in all its glory, it seems unlikely that any of the museum’s inquisitive viewers will be able to separate the original De Havilland 2 parts from its digital counterparts – a factor that’s both a nod to 3-D technology’s outstanding results and Thomas’s own creative vision.