For much of the last 70 years, someone who fought for both America and Russia might bring to mind some Cold War espionage, a double agent or a defecting citizen. But in World War II, for the only American to have fought in both the U.S. Army and that of the U.S.S.R., the story is one of diligence, endurance, luck, and a journey home.

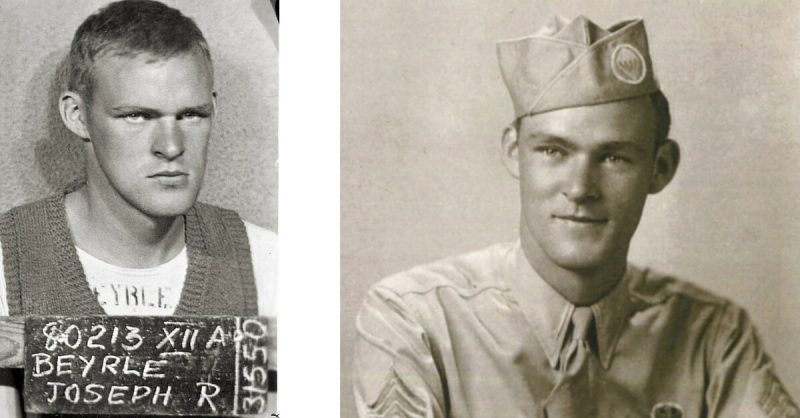

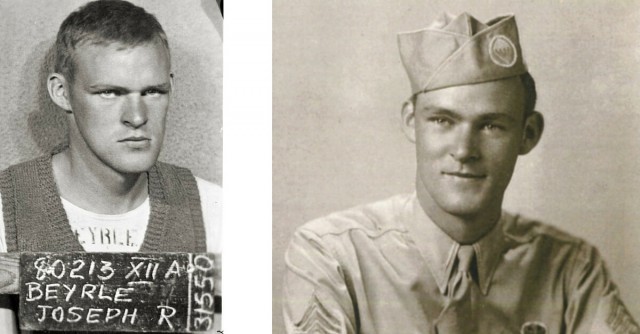

Joseph Beyrle was a paratrooper from Muskegon, Michigan. He was born in 1923, graduated high school in 1942, and turned down a baseball scholarship to the University of Notre Dame and instead joined the army to serve in the parachute infantry.

Beyrle served in the 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 101st Division, also called the Screaming Eagles. He specialized in radio communications and demolition.

Stationed in Ramsbury, England before the D-Day landings in 1944, Beyrle ran missions behind enemy lines. Twice, he was flown into German-occupied France and parachuted down with gold for the French Resistance.

Then came D-Day and Operation Overlord. Before more than 5,000 ships landed the Allied troops on the beaches of Normandy in the morning hours of June 6, 1944, some 1,200 planes flew over that land to drop thousands of paratroopers over the Germans. The casualties in this first wave were heartbreakingly high.

Remarkably, Beyrle survived the drop. He was flying in a Douglas C-47 Skytrain in the night lit up by German searchlights and anti-aircraft fire when the plane was hit. Beyrle jumped out at the altitude of 120 meters for a hard landing on a church roof in St. Come-du-Mont.

He never met up with the rest of his scattered troop, but managed to complete several sabotage operations, including blowing up a power station, before stumbling into a German machine gun nest several days after his landing.

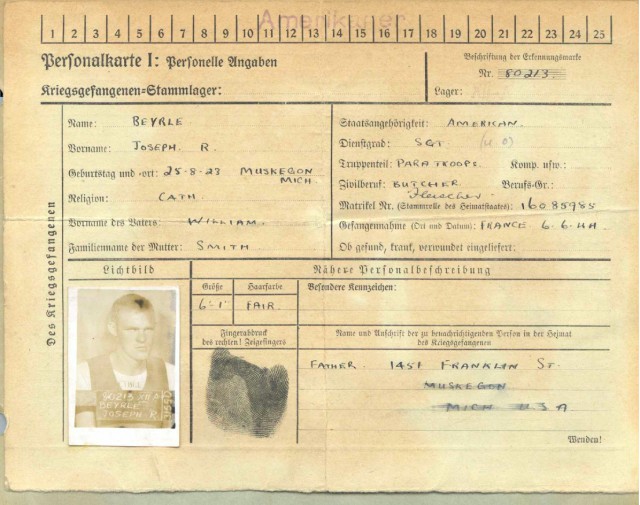

The German soldiers captured Beyrle, who spent the next seven months as a POW. He was moved through seven different camps and escaped twice, unsuccessfully. On the second of these attempts, Beyrle, and his fellow soldiers boarded a train that they thought was headed for Poland, so they could meet up with the Red Army, hoping that mutual interest with the Americans would lead to cooperation and then, with any luck, to freedom.

The train, instead, delivered them to Berlin. There, they were reported and captured. Beyrle was beaten and tortured by the Gestapo, who insisted that he was an American spy that had parachuted into Berlin. “Luckily,” the German army intervened, enforcing their jurisdiction over POWs, which the Gestapo did not have.

Joseph Beyrle’s POW File

Beyrle was then placed in the POW camp Stalag-III C in Alt Drewitz, in Western Poland. Here, Beyrle made his third bid for freedom in January 1945. This time, he made it. As he snuck East, the Soviets advanced West and Beyrle ran into a Russian tank battalion in the 1st Guard Tank Army.

This is the part of an already incredible story where one might start to wonder if we’re taking this from WWII or some Hollywood fantasy! The captured American soldier, making a desperate bid to return home meets the female captain leading tanks for the Red Army to avenge her destroyed home where her husband and entire family were killed during the German invasion.

Beyrle waved a pack of Lucky Strike Cigarettes and called out the only Russian words he knew, “Amerikansky tovarishch!” (American comrade). Alexandra Samusenko (the same age as Beyrle, 22), the only female Russian tank commander, would soon be convinced by the American soldier she saved to let him fight by her side on their advance to Berlin—a common enemy for two young soldiers in anything but common positions.

Alexandra Samusenko in 1943

Samusenko was just a young teenager when she joined the Red Army as a private in the infantry. She went through the tank academy and became an officer. When her tank crew took out three German Tiger I tanks in the Battle of Kursk, she earned the Order of the Red Star. This battle was a major turning point for the Soviets in WWII and one where, combined, the two opposing armies sent in over 15,000 tanks.

Beyrle spent a month fighting alongside his new battalion. On what must have been an incomparably cathartic day, they liberated Stalag-III C, the last prison camp Beyrle was held in.

In early February, Beyrle was wounded in an attack from German bombers and transported to a hospital in Poland. There, Soviet Marshal Georgy Zhukov, interested in, obviously, the only American in the hospital, came to speak with him and learn his story. He soon gave Beyrle official papers to locate and rejoin U.S. troops.

From the hospital in Poland, Beyrle hopped into a convoy back to Moscow, to seek out the American embassy. Unfortunately, his story had already taken a dark turn that would make the rest of his journey home difficult.

Beyrle’s dog tags had been found in Normandy soon after D-Day, on what is now presumed to be a dead German soldier. His family, back in Muskegon, Michigan, had been informed of the death of their brave volunteer in September 1944.

Needless to say, the American embassy didn’t believe he was who he claimed to be. After persistence and insistence, Beyrle managed to get the embassy to take his fingerprints and his identity was indeed confirmed.

On April 21st, 1945, Beyrle returned home to Michigan. World War II and his long journey were coming to an end.

In 1994, to mark the 50th anniversary of D-Day, Beyrle was honored at the White House by both U.S. President Bill Clinton and Russian President Boris Yeltsin. For the next ten years, Beyrle received a lot of publicity in both the U.S. and Russia for his amazing journey and the symbol of cooperation he was for the post-Cold War countries. He died in 2004, at the age of 81.

It is interesting to wonder if he ever thought of his old comrade, Samusenko, the woman who saved his life. Sadly, she died some 70 km outside of Berlin, run over by friendly tank caterpillar tracks in the dark. Beyrle had said she was a symbol for Russian courage and fortitude. He, undoubtedly, a symbol of the same for the Americans.

By Colin Fraser for War History Online

Sources:

- Alexandra Samusenko-Wikipedia

- Joseph Beyrle-Arlington National Cemetary

- Joseph Beyrle-Wikipedia

- All photos from Wikipedia