Standing only five foot tall in a line of thirty other young men, Kennith Ritchie waited for what everyone knew what was to come – they were going to Viet Nam. Drafted in Oklahoma when he was nineteen, Ken had been a jockey and a hairdresser. Now he was to be a soldier. A Marine officer walked in to see the new draftees. He counted the first five and said, “Congratulations, gentlemen. You are now United States Marines.” Ken was sixth in the line that day. Thinking he had dodged a rough assignment, he had no idea what was to come.

During boot camp, he took a lot of ribbing for his size but was tough enough to stand his ground. Being raised in the country on farm and ranch land, he had a slight advantage over the “city boys” who were unfamiliar with getting dirty. The country boy adapted to the tough conditions well. All the rocks chunked at trees, fences, and birds prepared him for grenade training. Being a little guy, he wasn’t expected to be able to throw far. But when holding a live grenade and asked, “How hard can you throw Ritchie?” his reply was, “I don’t know, but hard enough to get rid of this grenade!”

Thinking back to that time and the sergeant who had been so rough on the boys he has mixed emotions. The man might deserve a punch in the nose, but Ken would probably give him a hug. The training he received in boot camp likely saved his life more than once in the jungles of Viet Nam.

Transport of troops in 1965 was aboard a World War ship. Ken learned right away he wasn’t meant to be a sailor. Feeling somewhat trapped on board caused him to be even more anxious. The trip was to take twenty-eight days. Approximately 3000 soldiers were aboard and the sleeping quarters existed of bunks stacked six deep. And, of course, the shortest guy in the outfit, Ken, got the top bunk. One of the men was seasick every day. He spent much of his time at the rail, vomiting over the side. Walking around with saltine crackers, the least sound or smell would activate his nausea.

On one occasion, the miserable man was sick in private, vomiting out the anchor opening. Some of the guys trussed Ken up and dropped him over the side of the ship with a Polaroid camera. He said it was a long way down to the water and was very happy to crawl back onto the deck. He couldn’t swim. Looking back, he thinks about the crazy things they did; but remembers they were only nineteen-year-old kids faced with a grave future.

Ken had a buddy who convinced him to volunteer for KP duty. He was hesitant, but the friend insisted. From that day forward Ken enjoyed ice cream and hot showers in fresh water. All he had to do was keep the salt and pepper shakers full. It was a pretty good deal, and he was glad he got KP duty.

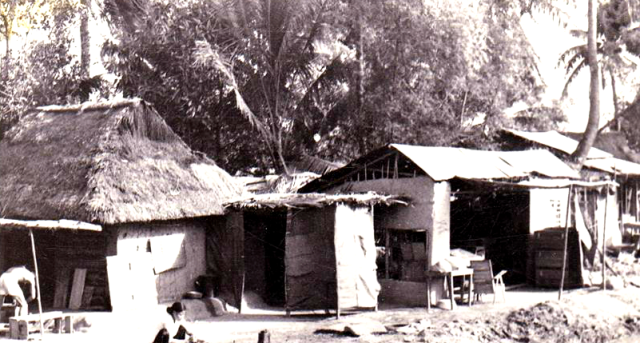

When at last they arrived at their destination, the men were loaded with gear and lowered into landing craft. Down inside that metal box, men were crowded together, and darkness covered their eyes, as they bounced through the choppy surf to the beach. Then suddenly, the ramp let down, daylight flooded the craft, and they were there. Viet Nam.

At first assigned to a transport group, Ken drove a Jeep for a Captain and delivered “beans, bullets, and band-aids.” He was spotted by a former trainer and found himself with the label: Tunnel Rat. His small stature, tough nature, and not being claustrophobic fit the situation well. He said it seemed the whole country had tunnels. He would go in with a pistol and a knife – though the knife was the weapon of choice should he encounter the enemy. Firing a gun in the tunnel was like, “Stickin’ your head in a 55-gallon barrel and firing a .44 magnum.

The red clay of the area made good tunnels, but during monsoon season, things got a little sticky. Not only might the enemy be lurking around a bend, but Ken encountered masses of big, brown spiders sheltering from the rain. He said it seemed like millions of spiders were ahead of him. But, having a mission and duty, he put his head down and forged ahead, allowing the masses of spiders to crawl across his body. Even fifty years later, Ken gets the heebie-jeebies thinking about it. But kids like to hear that story. Not surprisingly, Ken didn’t care for close spaces after his time as a Tunnel Rat.

Soldiers were dropped into certain areas by helicopter. The guys always gave each other a hard time, teasing and insulting each other good-naturedly. Ken told one chopper pilot he was pretty sorry for dropping them off in the jungle and leaving them there. The pilot quipped back, “Yeah, but you love me when I come back and get ya!”

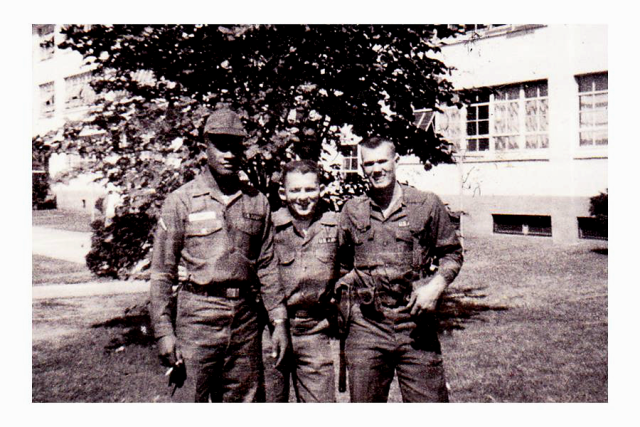

Camaraderie was common. Close friendships were not. Occasionally solid relationships would develop, but most often the men tried not to get to close to anyone. They never knew if it might be a dead buddy they have to zip up in a body bag.

Ken’s unit had a pet monkey for a time. They would tie his leash to a machine gun mount on a vehicle. Strangely, the little monkey did not care for the native Vietnamese people. He would scream and bare his teeth when anyone other than the American soldiers approached. The guys thought of him as a pretty good warning system, plus he was quite entertaining. Often the monkey would grab the steering wheel with all four paws and ride the turning wheel like a carousel.

On another occasion, a vehicle pulled up to camp with a large, dead tiger in the back. Soldiers were not allowed to hunt or kill native wildlife, so this was quite unusual. The situation made for a good story. Seems a guard on a bridge had to heed the call of nature and descended into the valley below the bridge to relieve himself. Suddenly, a huge tiger charged at him. Needless to say, he dropped what he was doing and emptied the clip of his automatic handgun into the creature.

While in Viet Nam, Ken was trained in Karate. The little guy got beat up for a while, but as his skills improved, he did a fair share of the beating. Before he left Viet Nam, Ken had attained the “brown belt” level of Karate and had a fair reputation in the sport.

Communication with home was sporadic. His folks apparently worried so much that they hadn’t heard from him, they contacted the Red Cross, who in turn contacted the chaplain of his unit. The chaplain threatened the young man with sessions of writing letters every day until he promised, and did, write weekly to his family. Incoming mail might bring several weeks’ worth of letters at a time. Ken would arrange them in post-mark order, to keep from getting the information contained in those letters in chronological order.

When a soldier was nearing the end of his tour, he was called a “Short Timer.” These men anticipated their extrication from the miserable jungle but didn’t know what to expect. Protests and anti-war sentiments back in the States made coming home a nervous proposition. However, when that jet aircraft took off and left Viet Nam behind, the entire plane load of soldiers going home shouted with joy. The roar was such that service people aboard were shocked. The boys were going home. The sensation became, even more, strange when they landed in San Francisco one hour before they had left the day before. Crossing the International Date Line caused them to gain back an entire day.

Each soldier was asked if he wished to see a staff psychiatrist. If he answered yes, a list of the questions which would be asked was provided along with the answers the man was to give. They were not to say what they really believed or what had actually happened. Though this seemed wrong, Ken played along not wishing to stay in the Army one second more than he had to. Within ten hours of landing in the US, the combat vets were turned out on the street.

Ken made his way back to Oklahoma and swore to never put on a green uniform again. But six months later he joined the National Guard. He realized of all the things he had done – hair dresser, jockey, farming, and ranching, he was best at being a soldier. He spent over thirteen years in the military and even tried to rejoin for Desert Storm. But the military would not accept Viet Nam vets into their ranks.

Despite all the mental trauma and physical problems as result of exposure to chemicals, Ken made a good life for himself. He hooked up with other vets and practiced PSTD therapy before anyone defined the disorder. Guys would sit around a table drinking coffee and talking. Ken tries not to dwell on the horrible things he experienced in war. However, several years ago, he recognized people needed to hear what he had to say. History books seemed to gloss over the Viet Nam War and not recognize the sacrifices made by soldiers and their families.

So he began speaking at schools, telling his stories and educating people on his view of Viet Nam. A principal at one high school came up to him at a Veteran’s Day program. He explained how one of Ken’s talks affected him deeply when he was in high school. That man saw what usually only military people understand: War wasn’t about only soldiers and sailors – it affected families even more.

In 2001, Ken and his wife formed a group of re-enactors who perform at the local historical museum. Made up of all disabled veterans or members of their family, the By Gone Days Gunfighters enjoy the camaraderie and fun of playing the good and bad guys. Over the years, Ken has battled a feeling of guilt for coming home in one piece when so many were injured or killed. He wondered for a long time why. At a family gathering including his faithful wife, their children, and grandchildren, he realized why he came home in one piece: for his family.