To be perfectly honest, one can’t be sure how to write a headline for the Medal of Honor actions displayed by Command Sergeant Major Bennie Adkins.

There were his frequent trips outside the perimeter during an extensive North Vietnamese assault, his lone manning of the mortar tube to bolster the defense, carrying wounded to the medevac chopper under heavy sniper fire, the hand to hand combat, and then missing the final evacuation helicopter because he refused to leave the wounded just about sums it up.

Despite these actions taking place during one engagement over multiple days, Adkins is estimated to have killed over 170 of the enemy but remarkably would walk away from this battle with only the Distinguished Service Cross.

However, when a subsequent review of awards took place decades later it became a no-brainer that these actions were far and above the call of duty even for one fighting for his own survival.

From Typist to Special Ops

Bennie Adkins was born in 1934 in the small town of Waurika, Oklahoma. By his own admission, Adkins didn’t originally set out for a career in the military. He had tried his hand at college but with all the pretty girls around, as he described it, he wasn’t doing so well.

He dropped out of college in 1956 which virtually ensured his subsequent draft the same year. However, Adkins seemed to take quite naturally to the Army and felt as if he had found his calling.

Strangely enough, this elite warrior’s resume would start out with him as a clerk-typist assigned to a garrison unit in Germany. He was later transferred to the second infantry division where he volunteered for the special forces after receiving airborne training.

Adkins would go on to serve more than 13 years with various special forces groups and three nonconsecutive tours in Vietnam.

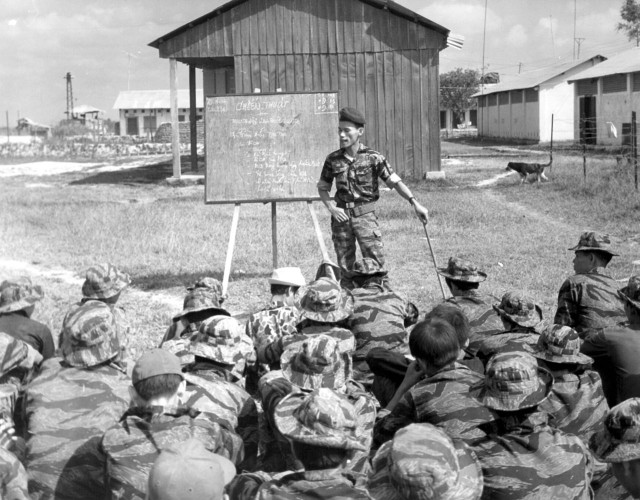

His first tour took place in 1963, is second 1966, and his final in 1971. And while he no doubt served honorably throughout all three, we are just going to focus on 1966 and specifically just about 72 hours of it. Adkins was serving with the 5th Special Forces group at Camp “A Shau” in the A Sau Valley.

The camp was in a strategic location close to the Ho Chi Minh Trail and used to train South Vietnamese members of the Civilian Irregular Defense Group. As a result, there were actually only approximately 15 or so American special forces defending the camp backed by a few hundred from the CIDG.

However, in the morning of March 9, 1966, a North Vietnamese force of over 2,000 attacked the camp in mass and it would be up to Adkins to even the odds a bit. Then a Sergeant 1st Class, Adkins ran through the heavy volume of enemy fire to man a mortar position ensuring effective fire would rain down upon the assaulting force.

Despite receiving wounds himself from well-placed enemy mortars, Adkins continued the gallant defense until there were no more mortars to fire.

Upon receiving word that some of his fellow soldiers were wounded in the center of the camp, he then braved heavy enemy small arms and sniper fire to retrieve the wounded soldiers and dragged them to cover.

The situation turned worse when South Vietnamese members of the CIDG defected during the fight began firing on the Americans. At this point, Adkins went outside of the camp during the assault and drew fire from the enemy in order to help cover the evacuation of a wounded comrade.

Then, when a critical resupply drop landed outside of the camp Adkins once again stepped outside of the wire to retrieve it. And this was just the first day.

Escape and Evade

The next morning of March 10, the primary assault was launched by the North Vietnamese with the intention of overrunning the camp.

ithin hours, he found himself alone man manning the mortar tube fighting off wave after wave of the enemy. As the situation grew grim, Adkins and several of the remaining soldiers withdrew to the communications bunker in order to make a final stand.

Running dangerously low on ammunition, they were finally given the order to evacuate the camp and Adkins helped dig through the back of the bunker in order to escape.

After destroying intelligence and medications gear, Adkins helped carry the wounded to the extraction point despite 18 separate wounds to his own body.

And while the South Vietnamese troops flooded the evacuation helicopters, Adkins and his group of fighters moved much slower as they insisted on carrying the wounded.

As the heavy fire continued to come in on the evacuation helicopters, Adkins was informed that the last bird had left.

Despite having just endured 36 hours of hard-fought battle, Sergeant First Class Adkins’ leadership would be required yet again.

For the next 48 hours, Adkins led his group of men through the jungles of Vietnam in an attempt to remain alive and evade capture.

Two days later, on March 12, Adkins and the men with him were finally evacuated by helicopter and at least for this week, the fighting was finally over. It is estimated that Adkins killed between 135 and 175 of the enemy during the battle to defend the camp and evade subsequent capture.

The commanding officer of Camp A Shau, Capt. John Blair, would go on record as saying “Sgt. 1st Class Adkin’s contribution to the defense of the camp and subsequent recovery of the survivors was far above and beyond that called for by duty.”

A Delayed Reward

For his actions that week, Sergeant First Class Adkins received the Distinguished Service Cross which ranks just behind the Medal of Honor in terms or priority. Some would argue that the secret nature of Adkins work and the controversies that often surrounded the CIDG prompted a lesser award to ensure less publicity.

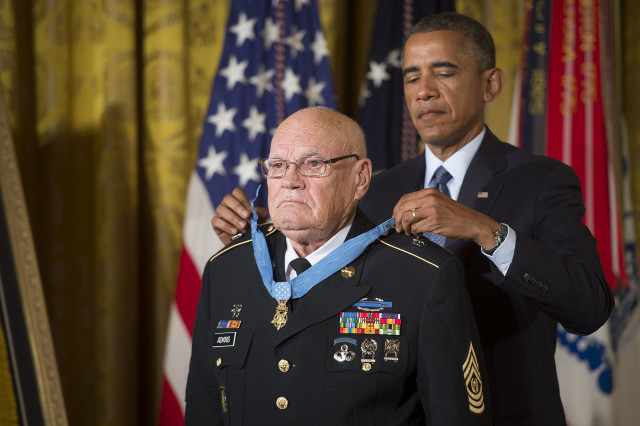

However, a 2002 investigation that examined recipients of the Distinguished Service Cross would identify two dozen whose gallantry would prompt an upgrade and high on that list was Benny Adkins.

In 2014, Benny Atkins received the nation’s highest military honor at the young age of 80. Fortunately for the student of history, the delayed awarding of the Medal of Honor gives us a renewed opportunity to look at one of the greatest examples of war fighting to have come out of the Vietnam War. It is hard to point to one specific act committed by Adkins during the several days of fighting that stand out above the other.

But if it were possible for a soldier to receive a medal of honor for each individual day of fighting in one battle, Command Sergeant Major Adkins might just be sporting a few of them.