The history of war is comprised of many occupational specialties necessary for military victory. Within the culture of Military Service, one would often find rivalries associated with these roles. For the Marine Corps, which is an organization centered around the infantry, this is most certainly the case.

Modern Marines will refer to infantry as Grunts and non-infantry types as POGs, or Persons other than Grunts. The POGs are reported not to be very fond of that term while Grunts are reported as caring very little about what the others think. Past eras – such as Vietnam – would demonstrate this rivalry as well where infantry were still known as Grunts, but those not on the front lines.

Those who had no front line experience were lovingly referred to as REMFs. RE stands for Rear Echelon – I’ll leave the rest of that acronym to the reader’s imagination. It may not quite be publishable, but it’s no less part of the nuance of military history for that.

For one Infantry Marine in Korea, a combat wound would place him in the rear with the equipment as a property Sergeant. Within a week, he was begging to be sent back to his unit fighting in the hills of Korea where he would eventually fall in combat and be awarded the Medal of Honor.

Corporal Joseph Vittori

Born in the small Massachusetts town of Beverly in 1929, Joseph Vittori would grow up as a teenager watching the Marines battle the Japanese in the Pacific. Upon graduating High School in 1946, he enlisted in the Marine Corps and was sent to the Marine Corps Recruit Depot on Parris Island to begin what would be a legendary career in the Marines. However, this legendary career would get off to a somewhat mundane start.

When a new Marine joins the fleet in modern times, they are often referred to as a “boot,” in reference to their having just left boot camp. Life can be hard as a boot, but it must have been spectacularly difficult for a new Marine in 1946 when the Corps was comprised of battle-hardened veterans who had fought their way from Guadalcanal to Iwo Jima.

Upon becoming a Marine, Vittori would serve in a variety of roles from 1946 to 1948 including time at the Norfolk Naval Shipyard, sea duty aboard the USS Portsmouth, and the Philidelphia Navy Yard before he was eventually transferred to the 2nd Marine Division at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina.

In 1949, Vittori was discharged after three years of service, and in these non-combat years, he returned home to Beverly where he would work as a plasterer and bricklayer. Then war broke out in Korea in June of 1950. He enlisted in the Marine Corps Reserve in September of 1950 for what he knew would mean a combat deployment to Korea.

The Marine, who had been too young for World War 2, no doubt spent his active duty time listening to the stories of that war from combat veterans. Well, he was about to get his chance to jump into the fray. After a period of training, he landed in Korea to join Company F, 2nd Battalion First Marines.

Fighting for Hill 749

Once in Korea, he would quickly find himself immersed in the back and forth struggle between the two Koreas. The South was bolstered by American and UN forces while the North would be aided by hundreds of thousands of Chinese troops. Vittori was wounded in June of 1951 near Yanggu and spent time in a field hospital where he was promoted to Corporal.

Once he recovered, he was assigned to be a property sergeant, which was a hard role for this Grunt to accept. Within a week, he was pleading to be sent back to his unit fighting it out in the hills of Korea so that he could serve alongside his friends.

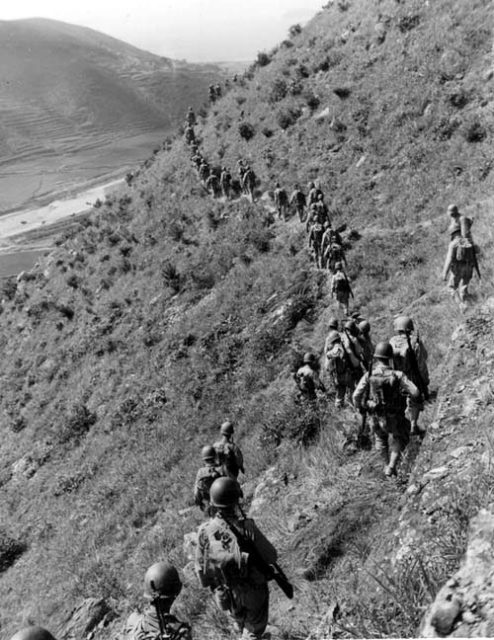

His request was granted, and while it would prove a fatal decision for him, the Marines he likely saved with his heroic actions would have much reason to be thankful. In September of 1951, during the Battle of the Punchbowl, Company F was given the task of assaulting up Hill 749.

Coming head-on towards the fortified positions, the Marines assaulted and made great progress until they were hit by a counter-attack that pushed them back. During the chaotic attempt to consolidate their positions, Corporal Joseph Vittori gathered up two other volunteers and charged the counterattacking North Koreans. In what would become a fierce hand-to-hand struggle, Vittori overwhelmed the enemy giving his company time to prepare for more attacks.

The next phase of his Medal of Honor action that day would see him volunteering to defend a machine gun position on the northern point of the line that was almost entirely isolated from the rest of the unit. When a 100-yard breach was made in the American lines due to dead or wounded, Vittori would find himself running from flank to flank firing upon the enemy from this position during the North Korean night attack.

In the pitch black, Vittori held off the enemy and manned the machinegun alone after the gunner was killed. The enemy had approached within 15 feet of Vittori’s position, but he held until mortally wounded by machine gun and small arms fire.

The Morning After

Vittori’s gallant one man stand allowed the Americans to hold the lines and deny the enemy physical occupation of the ground. His Medal of Honor citation would go on to say that he prevented the entire battalion position from collapsing.

When Vittori was found the next morning, there were over 200 dead enemy bodies strewn out in front of his position. And while he can’t be credited with all 200 himself, it is a safe bet that a high percentage of those dead North Koreans wished Corporal Joseph Vittori would have stayed a POG, REMF, or whatever they might have called those who spend the war in the rear with the gear.

All positions are of value in warfare and any who wear the uniform serve with honor and respect. However, it would seem that for some men the infantry is a calling and despite the high probability of death in a fierce struggle, they truly belong on the front lines rather than inventorying property in the rear.

Joseph Vittori’s Medal of Honor was presented to his parents in 1952 by President Harry Truman as a grateful nation, Marine Corps, and the men of Company F 2nd Battalion 1st Marines were truly thankful for his sacrifice.