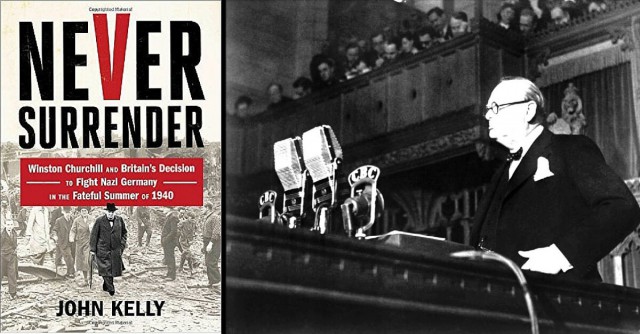

On 13th May 1940 Winston Churchill rose to speak in the House of Commons. “You ask, what is our aim? I can answer in one word. It is victory, victory at all costs, victory in spite of all terror, victory, however long and hard the road may be; for without victory, there is no survival.” There was a time when the post-war generation were uniformly steeped in this stuff of The Few and finest hours, but times have changed and Churchill’s age of defiance is slipping into history muffled by new priorities his victory quite correctly allows people to pursue instead of the demanding conformity and militarism of his enemies.

Churchill dominates this book by John Kelly allowing him to stand out against a gaggle of apparently spineless intriguers and journeymen who might have sold out the British Empire to the Nazis. Neville Chamberlain’s reputation, post appeasement; has never recovered and although he was far from alone in his particular quest for peace for his time all his sincerity of purpose and his many other attributes have been blown away by the events that followed Munich. It has always suited the definitive text that Churchill fought his way out of the wilderness to save his country in a ‘cometh the hour, cometh the man’ scenario bolstered by the collapse of a befuddled France, the Miracle of Dunkirk and the Battle of Britain.

Before his star began to wane later in the war Churchill could claim to have galvanised his country in pursuit of victory. The period of the ‘dark days’ may be high-octane drama, but it is a confusing sequence of events and it is important to cut through the propaganda of speeches and imagery to get a handle on what was happening.

This book approaches the subject from the position of a neutral. Mr Kelly is an outsider looking in without the distraction of any affinity to Britain or the British/English and none, apparently, for the hapless French. I found this refreshing especially as the Churchill of 1940 retains something of a cult status in American visions of wartime ‘England’ enhanced by his oratory and fierce antagonism to communism.

It is important to look at him and his convictions but this has to be set against the people he engaged with, whether they were pro or anti his stance on the Nazi menace. During the era of appeasement the Great War and the spectre of the empire’s million deaths haunted British politicians. Those ghosts will be roaming again during this year of the centenary of the Battle of the Somme and just as much lachrymosity will be spent agonising over interpretations of futility and sacrifice. But the distinction is those men of the 1930s knew the sacrifice had been necessary however painful it was for the country but it did not stop them seeking to avoid another almost at any cost. This creates something of a mirror image of Churchill on the day of his speech in May when the British Expeditionary Force was staring at its complete destruction.

Mr Kelly looks at the agony of France and the inextricable link with the British road to Dunkirk. If British politics seemed divided a look across the Channel makes it all look like child’s play. French politics was a basket case of factions, rivalries and instability ripe for the imposition of Vichy after defeat. The massive French army looked fantastic on Bastille Day or in the tunnels of the Maginot Line but it was a hollow shell of the great army that beat the Kaiser.

French incredulity that Britain could not mobilise a larger army in 1940 swerved the reality of the very fiscal paucity and demographics that hobbled their own army and in attempting to blame the British for their defeat all that was achieved was a short term boost for the right wing of French politics under Pierre Laval and his acolytes. Perfidious Albion remains a strong image, especially after Admiral Somerville opened fire on the French fleet at Mers-el-Kabir. Britain’s determination to fight on alone impressed neutrals and underlined to the Nazis and their puppets that the road ahead was, indeed, a long one.

For the British reader this book offers a seemingly objective look at the defiant months of 1940 when Churchill exhorted his country to “never surrender”. Despite all this Mr Kelly appears to have something of an attraction to the man who provided the roar for the British lion even though he identifies the points in his political career that offend some Britons to this day. It is much easier to find little sympathy for appeasers and procrastinators who filled important positions or the perennially ambitious like David Lloyd George. Befitting his real life role, Clement Attlee comes across as an example of quiet stoicism. He had seen the Great War up close, too, but he had no doubts about the need to defeat the Nazis and what this might cost.

The story cannot be told in full without reference to Britain’s relationship with the United States a while before it gained the millstone ‘special’ beloved by a string of British prime ministers after 1945. I have never had difficulty sympathising with the isolationists hoping to keep America out of the war. Whether they were ‘wrong’ can be debated until the cows come home because history caught up with and smothered their motivations. Part of the reason I like this book and the Yanks and Limeys we saw last year is because it does not lose sight of the truth that Franklin Roosevelt held his first duty to be to his own country but that saving the free world could and would have its advantages. America is both peripheral and essential to this story because one great alliance had to be mortally wounded before another could arise.

It is apparent that this book is primarily aimed at the American reader for whom the period probably defines their vision of Britain even in this age of Downton Abbey. Mr Kelly seeks clarity on the myths of Churchill and Chamberlain to place them in proper perspective of their time, not ours. There was a tendency for the Britain of those times to be blurred by the likes of Mrs Miniver even though Ed Morrow and Ernie Pyle reported on the reality.

Regardless of all this a lot of Americans came and saw wartime Britain and hated the stiffness and archaic nature of institutions. Many others came to like and even love the place but, really, they all just wanted to leave it all behind and go home when the job was done. Absolutely right! Mr Kelly creates a cartoon of Britain, in the fine art sense, rather than in the micro-detail of a finished Constable or Canaletto. There are some details and geography that I found a little difficult but these are distractions from a well-paced, atmospheric and broadly empathetic text.

As a Francophile I have an enduring sympathy for the agony of France, but I was raised on the defiance and valour of Britain during those climactic years. In the summer of 1940 my father was a 21-year-old Army reservist guarding a vast expanse of Norfolk coastline seemingly all by himself. I still had the wellington boots the army equipped him with as late as 2001. Pride in the collective history defined by David Low with ‘very well, alone’ and a multitude of other references is something I could never let go.

I can walk you through the wartime London of my parents and perpetuate the myths allied to treasured truths of the Blitz and all the spirit of defiance a fading empire could muster just when it mattered most. It is a vision that will never be surrendered. The twists and turns on Churchill’s long and hard road before the destruction of the Axis Powers are imprinted on my family history and those of my friends. Britain then, as now, is not a perfect place; but the decision to fight was the right one however distant that now seems.

This isn’t the first and won’t be the last book on those times, but Mr Kelly has recreated the gathering storm with skill and a degree of warmth and there is enough here even for the casual reader looking into the precipice of 1940 when the future of the world was in the balance.

Reviewed by Mark Barnes for War History Online.

NEVER SURRENDER

Winston Churchill and Britain’s Decision to Fight Nazi Germany in the Fateful Summer of 1940.

By John Kelly

Scribner

ISBN: 978 1 4767 2797 4