By Jeremy P. Amick

A mother’s love for a child can be an abstract and unwavering force that yields to no person or object. Few would argue that such fondness often transitions to a protective instinct, which then encourages the parent to defend their child from all threat or harm.

So when a child leaves a mother’s warm embrace to join the military under the threat of war—or, in some cases, death—it must certainly be the height of stress or worry for the doting elder left behind.

Yet during World War II, one local mother experienced the unfortunate reality of sending her son off to war, not realizing that she would spend the next several years struggling to cope with the unexpected loss.

Born in Lohman, Mo., on February 15, 1913, Chester Everett Strobel was the only child of Louis and Emma Strobel and grew up watching his parents engaged in mercantile endeavors. However, the couple’s young son would soon step up to fill in for his departed father.

“When Chester was 16 years old his father died and he became the mainstay of his mother,” Strobel’s obituary explained. “With loving devotion he was attached to his mother who in turn bestowed upon her son the fullness of her motherly love and affection.”

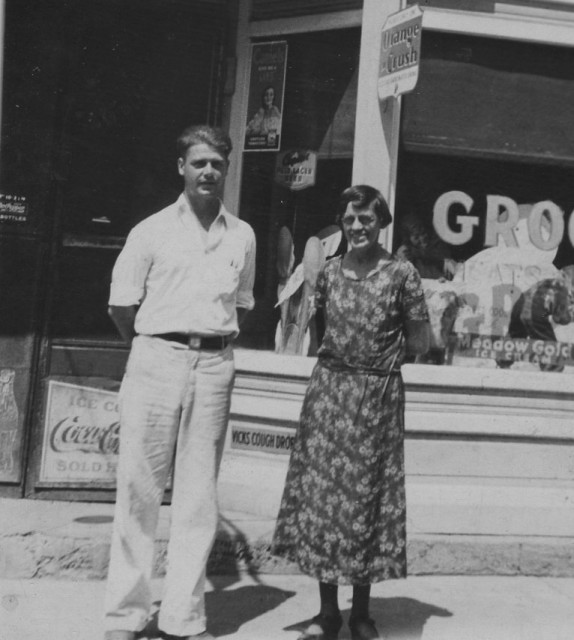

For many years, “Chetty”—as Lohman resident Gert Strobel notes was Chester’s nickname—helped his mother operate their store that was located in what is now the front section of the MFA Exchange building in Lohman.

“They had everything (in the store)—candy, flour, oatmeal, beer,” said Gert Strobel. “It was all in bulk; there was nothing in packages.”

As is often the case with young men, Chester developed affections for a young woman, Florence Meister of Jefferson City, and the two were married on September 26, 1942—twelve days following “Chetty’s” enlistment in the U.S. Navy.

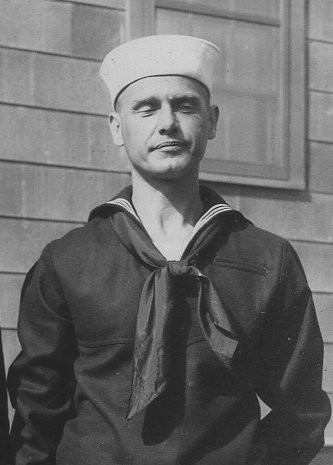

The young sailor soon said his goodbyes to the two women who meant the world to him and departed for naval training at Great Lakes, Ill. Several months later, he began his first active duty assignment performing operations in the Atlantic aboard the USS Augusta.

Strobel continued his Atlantic-based service while later serving aboard the USS. Ludlow, but in April 1943, he was introduced to operations in the Pacific Theatre when transferred to the U.S.S. Isherwood—a recently commissioned destroyer.

“During the next two years of its operations (USS Isherwood), it traveled more than 115,000 miles” and took part in combat operations in locations including the Kurile Islands and the Philippines, as Strobel’s obituary described.

But, as noted on the website for The National Association of Destroyer Veterans (NADV), an unfortunate event on April 22, 1945 robbed a community of one of its native sons.

With little warning, the Isherwood came under attack by three Japanese planes while operating near the Ryukur Islands off the coast of Okinawa. All hands reported to their battle stations, but not in time to prevent the deadly consequences that soon followed.

An article on the NADV website explains that one of the planes was on a kamikaze (suicide) run and “hit squarely on the No. 3 five-inch gun mount, killing or wounding most of the men on duty within the mount and its ammunition handling room.”

What followed was certainly pure bedlam when a depth charge exploded 25 minutes later, killing many more crewmembers. It is believed that the 32-year-old Strobel was killed instantly when the kamikaze plane struck the Isherwood.

A Western Union telegram received near the end of April 1945 notified Strobel’s wife that her “husband Chester Everett Strobel … was killed in action while in service of his country.”

Fellow church and community members celebrated Strobel’s life during a memorial service held on July 8, 1945 at St. Paul’s Lutheran Church in Lohman, where the young sailor had been a member. The veteran’s remains were interred in the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Honolulu.

Though Chetty’s wife later remarried and moved to Barnett, Mo., where she lived until her death in 1990, his mother (who passed away in 1966) never lost hope that her only child might somehow have survived the deadly encounter described in a brief telegram.

Many in the Lohman community continue to share the story of Strobel’s mother leaving her porch light on at night, clinging to the belief her son might return home; yet a tribute published in the April 20, 1947 edition of The Sunday News and Tribune provides a glimmer of what appears to be her acceptance of the loss of her son.

“His smiling way and pleasant face are a pleasure to recall; he had a kindly word for each and died beloved by all,” wrote his mother, adding, “Some day we hope to meet him, some day we know not when, to clasp his hand in the better land, never to part again …”

Jeremy P. Ämick writes on behalf of the Silver Star Families of America.

Jeremy P. Ämick

Public Affairs Officer

Silver Star Families of America

www.silverstarfamilies.org http://www.silverstarfamilies.org Cell: (573) 230-7456