In just 70 hours, over 60 men with the US Army’s 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment pulled off one of the most brazen military heists in recent history. Dubbed Operation Mount Hope III, the top-secret clandestine mission went off without a hitch, despite sand storms and the looming threat of Libyan forces. Without a single shot fired, they managed to steal one of the Soviet Union’s most prized possessions: a Mil Mi-25 Hind D attack helicopter.

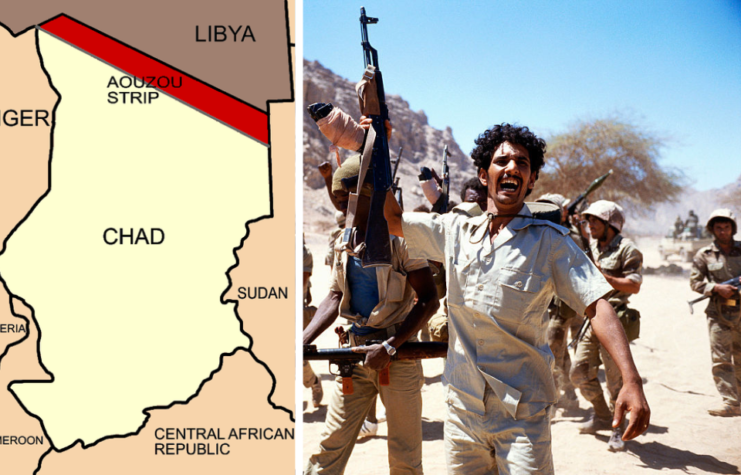

Chadian-Libyan War

Operation Mount Hope III took place directly following the end of the Chadian-Libyan War, which raged across Chad between 1978 and 1987.

Tensions between both had began a decade prior with the rise of Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi. As part of his siege of power, Gaddafi claimed a piece of land along the Chad-Libya border known as the Aouzou Strip, a 44,000-square-mile piece of land consisting almost entirely of the Sahara Desert. With support from Eastern Bloc countries, he trained and armed a Chadian group of insurgents known as the Front de libération nationale du Tchad (FROLINAT).

On August 27, 1971, Chad accused Egypt and Libya of supporting a coup d’etat against President François Tombalbaye. When it failed, Tombalbaye cut all diplomatic ties with Libya and Egypt, and invited Libyan opposition groups to relocate themselves to the country. In response, Gaddafi chose to officially recognize the FROLINAT as the true Chadian government.

The countries resumed diplomatic relations in 1972, when Chad agreed to cede the Aouzou Strip to Libya in exchange for £40 million. Chad and Libya signed a Treaty of Friendship in December 1972 to make the deal official.

By 1978, the newly-peaceful relationship between Chad and Libya had all but dissolved. The former became a war zone, with Chadian groups backed by France and the FROLINAT supported by Libya. The French intervened in the conflict with no luck, and it continued well into the 1980s.

At the start of 1987, Libyan forces still bolstered impressive numbers: 8,000 troops and 300 tanks. However, they’d lost the support of their Chadian allies, who’d previously provided assault infantry and reconnaissance forces. Without this help, Libya was left high and dry in the desert.

Meanwhile, the Chadian National Armed Forces (FANT) had increased their military force to 10,000 troops who were equipped for the desert war with fast and sand-proof Toyota pickup trucks armed with Missile d’Infanterie Léger Antichar (MILAN) anti-tank guided missiles. The vehicles gave this part of the conflict the nickname, “Toyota War.”

Mil Mi-25 Hind D

The Toyota War ended in September 1987, after the Chadians outnumbered the Libyans and regained control of the Aouzou Strip, only for it to fall to Libya once more during a second battle. The Libyans lost thousands of troops and $1.5 billion worth of tanks, weapons and equipment that were destroyed or abandoned during their retreat. Twenty aircraft were also left behind at the air base at Ouadi Doum – one, in particular, caught the attention of the US military.

The Mil Mi-25 Hind D was among the most advanced Soviet helicopters of the time, and the US had nothing like it. Dubbed the “devil’s chariot” by forces in Afghanistan, it’s both adaptable and unbeatable, serving as an attack and transport chopper. It has six suspension weapon units on its wingtips, is equipped with a four-barreled YakB-12.7 machine gun and can accommodate up to 12 anti-tank missiles.

The Mi-25 Hind D is also heavily-armed, with a sophisticated high-explosive fragmentation warhead capable of penetrating thick armor. The 18,000-pound beast is fast and adept at combat, as well as troop transport, making it the ultimate chopper – and also incredibly difficult to steal from right under Libya’s nose.

Operation Mount Hope III

After negotiations between American, French and Chadian forces, the US military was granted permission to recover two Mi-25s, one of which was at Ouadi Doum. The mission was assigned to the US Army’s 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment, also known as the “Night Stalkers.”

Their task posed several unique challenges. Not only did they have to fly to the area in the middle of the night, they then had to slung-load the massive helicopter and fly off without losing it or tipping off nearby Libyan guards. In April 1988, the troops began training with Boeing MH-47 Chinook helicopters around the deserts of New Mexico. One carried an external load of six 1,900-liter water containers to mimic the weight of the Mi-25 Hind D.

On June 10, over 60 personnel boarded a Lockheed C-5 Galaxy with two MH-47s loaded in the cargo hold. Departing from Fort Campbell, Kentucky, the team flew to N’Djamena International Airport, in Chad, and disembarked the C-5, loading up the two helicopters before departing for their 550-mile trip to Ouadi Doum at midnight.

Keeping the mission a secret was the only way it would succeed; Libyan forces remained in the target area and could easily be tipped off. There were also fears the Mi-25 Hind D would be bombed as part of the Soviet Union’s plan to prevent clandestine recovery efforts like that of Operation Mount Hope III.

At Ouadi Doum, a team was already on the ground preparing the helicopter for transport. Flying it was deemed too risky, as it had a bullet hole in one of its engines, so the rotors were removed in preparation for transport. The MH-47s then arrived on the scene. Their additional fuel tanks were removed to ensure they could lift the Soviet chopper, which was slung-loaded underneath one of the American helicopters, before taking off toward safety with the second in tow.

The additional fuel tanks and rotor blades were flown out on a Lockheed C-130 Hercules.

Just as they were approaching N’Djamena International Airport, the team was engulfed by a sand storm, which virtually clouded out any visibility. Both MH-47s flew slowly and within sight of one another to prevent a collision as they braved the onslaught of desert dust. Remarkably, they safely landed with the Mi-25 Hind D – not a single bullet fired or man left behind.

What happened to the Mil Mi-25 Hind D?

After the storm had settled, the Mi-25 Hind D was loaded onto a C-5, while the two MH-47s were put into a second.

The Soviet helicopter arrived at Fort Rucker, Alabama on June 16, 1988, where it was brought up to flying status and thoroughly evaluated to inform and train personnel on enemy capabilities. It was even flown during training exercises, acting as an opposing force for US helicopters and soldiers on the ground.

More from us: Battle of Norfolk: The Largest Tank Battle of the First Gulf War

Want War History Online‘s content sent directly to your inbox? Sign up for our newsletter here!

In 2012, the Mi-25 Hind D was saved from the scrapyard and put on display at the Southern Museum of Flight in Birmingham, Alabama, where it remains today.