During WWII, Sub-Lieutenant Saburō Sakai served as a naval aviator with the Imperial Japanese Navy. He claimed 64 victories, one of which was made after he had been blinded in an eye and had half of his body paralyzed.

Born in 1916, Sakai was a direct descendant of samurais. He was the third of four sons, which is exactly what Saburō means – third son. In 1933, he joined the Japanese Navy and began quickly climbing his way up the ranks.

In 1937, however, he decided to become a pilot. He did so well that he graduated first in his class, for which he received a silver watch from Emperor Hirohito. By 1938, he became a Petty Officer Second Class where he saw aerial combat during the Second Sino-Japanese war. Though wounded, he achieved his first kill in October 1939 when he shot down an Ilyushin DB-3 bomber.

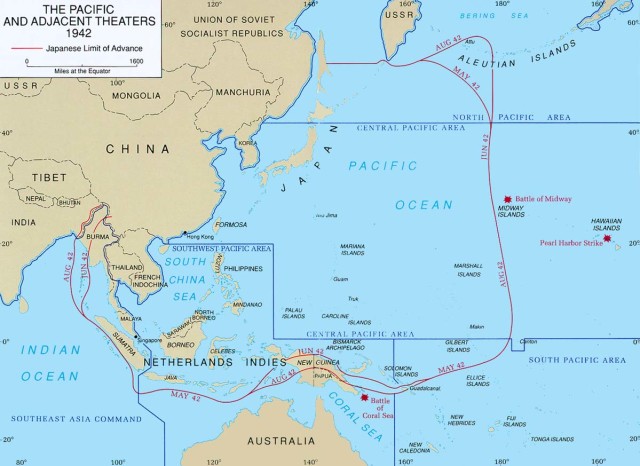

Sakai participated in the invasion of the Philippines in December 1941 where he downed three US warplanes over Clark Air Base. He also shot down the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress piloted by Captain Colin P. Kelly, though he never received official credit for it.

In 1942, he saw action in the Dutch East Indies where he began to develop an independent streak. Japanese pilots were ordered to shoot down any planes that weren’t Japanese, regardless of whether they were military or civilian craft.

Sakai saw a Dutch Douglas DC-3 carrying civilian passengers, so he got ready to fire. Looking out at him through one of the windows, however, was a blond woman and a child which triggered a flashback. The woman looked like an American teacher who had been kind to him back in Japan, so he couldn’t shoot.

He instead flew forward and signaled the pilot to keep going. The pilot and passengers saluted him in gratitude and did just that. Returning to base, Sakai didn’t report the incident and only included it in his later memoirs.

Sakai was part of the Tainan Kōkūtai, an air group formed in Tainan City, Taiwan (formerly Japanese territory) on 1 October 1941. Part of the 23rd Air Flotilla, it produced more flying aces than any other unit in the Japanese military, making them national heroes in Japan. The Tainan flew in Mitsubishi A6M2 Zero fighter planes which had greater speed and maneuverability than those used by the Allies, so Sakai decided to show off.

On the evening of 16 May 1942, Sakai was on the island of Lae listening to an Australian radio program broadcasting Camille Saint-Saëns’ “Danse Macabre,” when he got an idea. The next day, he participated in an attack on Port Moresby, but after the rest had flown off, Sakai and two others flew loops in close formation to the tune of Danse Macabre to demonstrate their aerobatic skills.

The next day, an Allied bomber flew over the Lae airfield and dropped a note. It thanked the Japanese for their aerial demonstration, invited them for a return performance, and promised them a warm reception when they did. Sakai and his friends got in serious trouble for that incident, but they didn’t’ regret it.

The Allies, however, didn’t wait for a repeat performance. In August that year, they launched Operation Watchtower, the first major offensive against the Japanese. Its aim was to secure America’s access to Australia and New Zealand, and to isolate the Japanese bases at Rabaul and New Britain.

The Japanese were eventually defeated in that battle, so the Americans took the island of Guadalcanal and its Japanese base, renaming it Henderson Field. The Japanese maintained their hold over the islands of Rabaul and New Britain, but they wanted Henderson Field back.

This resulted in almost daily air and sea battles collectively known as the Guadalcanal Campaign – one which Sakai almost didn’t survive.

On August 7, during Operation Watchtower the Americans attacked the islands of Tulagi and Florida, taking the Japanese by surprise. Sakai and three others from the Tainan Kōkūtai shot down an F4F Wildcat while Sakai alone destroyed an SBD Dauntless dive bomber flown by Lt. Dudley Adams – but not before Adams fired a shot into Sakai’s canopy.

Sakai wasn’t hurt and Adams managed to parachute out of his plane before he crashed. The next day, Sakai’s luck changed.

Flying over the island of Tulagi, the Tainan tried to ambush eight SBDs. Sakai dove under and aimed for the one flown by Ensign Robert C. Shaw, mistaking it for a Wildcat fighter. But Shaw’s VB-6 Dauntless was a dive bomber with a rear-mounted twin 7.62 mm machine gun.

Sakai had avoided Adam’s shot into his canopy, but not Shaw’s. The bullets blew off his canopy, one took out his right eye and paralyzed the left side of his body. His Zero plummeted to the sea below.

With his good eye blinded from all the blood, Sakai pulled out of the dive and looked for an Allied ship to crash on. But the rush of cold air cleared his head a bit and when he could finally see, he realized he had enough fuel to return to base.

It took him almost five hours to reach Rabaul, nearly crashing into a group of parked Zeros. He had to circle four times, nearly running out of fuel before he finally managed to line up on the runway properly.

Men helped him get off and were about to rush him to the field hospital, but he refused. Sakai wanted to make his report first. He did so then passed out. They sent him back to Japan on August 12 for surgery which was done without anesthesia because Japan was running low on supplies, but they couldn’t restore sight to his blind eye.

They finally discharged Sakai in January 1943 and ordered him to spend the rest of the year training pilots. He obeyed, but his samurai blood found it humiliating. With Japan clearly losing the air war, he prevailed upon his superiors to let him fly in combat again. In November 1943, Sakai was promoted to the rank of Flying Warrant Officer. In April 1944, he was transferred to Yokosuka Air Wing, which was deployed to Iwo Jima.

Sakai made his final kill on 24 June 1944 when he downed an F6F Hellcat. Later he was transferred back to Japan where he took part in the Japanese air force’s last mission of the war. He attacked two reconnaissance B-32 Dominators on 18 August, which were conducting photo-reconnaissance and testing Japanese compliance with the cease-fire. He initially misidentified the planes as B-29 Superfortresses but both aircraft returned to their base at Yontan Airfield, Okinawa.

After the war, Sakai retired from the Navy. He became a Buddhist acolyte and vowed he would never again kill any living thing, not even a mosquito. He died in Tokyo on September 22nd 2000.

Source: Wikipedia, New York Times