In 2002, the BBC launched a nationwide poll asking Britons who they thought the Greatest Briton was. Among those nominated were William Shakespeare and Princess Diana, but the public ended up choosing someone else entirely.

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill was born to the Lord Randolph Churchill, the third son of John Spencer-Churchill, 7th Duke of Marlborough, but his mother was Jennie Jerome of Brooklyn, New York. In fact, he was the first person to receive an honorary US citizenship.

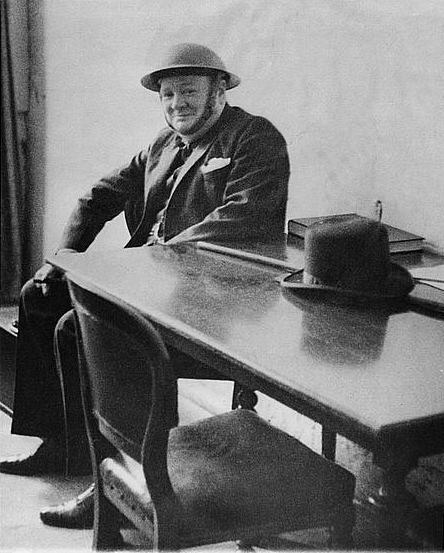

Most associate Churchill with WWII when he was Britain’s Prime Minister. They also remember his books, inspiring speeches, and witticisms – even though he had a slight stutter and a lisp. His grasp of military tactics was equally remarkable given that he twice failed the entrance exams to the Royal Military College at Sandhurst.

Born on 30 November 1874, Churchill graduated from Sandhurst at 20 to become a second lieutenant in the 4th regiment of the Queen’s Royal Hussar’s (a cavalry regiment). In 1895, he traveled to Cuba during their war of independence, which is where he developed a taste for Havana cigars and wrote his first article for a British paper, sealing his reputation as a war correspondent.

It was during a visit to New York that he met Bourke Cockran – the politician who had a major influence on his political views and oratorical style. The following year, Churchill saw action in India at the Siege of Malakand, which he wrote about in a book.

Churchill went to Egypt in 1898 and again saw action at the Battle of Omdurman the following year. He later resigned his position to campaign for a parliamentary seat, but that didn’t pan out, so he became a full-time correspondent for the Morning Post and wrote another book when he was taken prisoner by the Dutch.

It happened in South Africa. He was supposed to cover the Second Boer War, but couldn’t resist mounting a scouting expedition into Dutch-occupied territory. He escaped his captors and made it to the Portuguese territory of Lourenço Marques (now Maputo in Mozambique). For this and similar exploits, they declared him a national hero in Britain.

This inspired him to rejoin the military, though he kept his writing job. His last order of business was to help end the 118-day Boer Siege of Ladysmith (1899-1900), after which he returned to Britain where he again dabbled in politics.

In 1910, he became involved in the Tonypandy Riots when police shot at Welsh coal miners, hurting his reputation. He made up for this the following year by helping to draft the Insurance Act of 1911 which introduced minimum wage to Britain.

That same year, he became First Lord of the Admiralty and worked to modernize the military by replacing its use of coal with oil. He also began Britain’s involvement in the Persian Gulf to secure oil supplies, which is how he nearly destroyed himself.

When WWI broke out, he suggested an invasion of the Ottoman Dardanelles, which ended disastrously for the British and again hurt his career. He also vacillated on the idea of a separate Jewish state which led to consequences that are still being felt today.

Churchill again alienated himself from the public and the government in 1934. Convinced that Germany was rearming, once more, he urged the government to act. Having just gone through WWI, however, few in Europe believed him or wanted to.

As the Nazis grew stronger, the British government under Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain sought a policy of appeasement. The result? A more belligerent Germany.

Things came to a head in 1939 when Germany occupied Poland. Churchill wanted to invade Narvik, Norway, and Kiruna, Sweden to mitigate the German advance, but Chamberlain again refused. So in April 1940, Germany took Norway. Although the Allies sent help, it was too late.

It became clear that Chamberlain wasn’t up to the task, so he was forced to resign. Churchill became the prime minister on May 10, 1940 and flew to France to assess the situation. Sadly, he realized the country would fall, leaving Britain alone to fight the war.

As one country after another fell, many in Britain thought it best to sign an armistice with Germany, but Churchill refused. His brilliant speeches changed public opinion and Britain settled down for yet another war.

To make sure they did, he did something unusual for a British noble. In a society divided along class lines, he made frequent public appearances and engaged the people, making him a very modern politician.

Since he had a more intimate understanding of war than most of his colleagues, Churchill knew that Britain couldn’t rely on conventional warfare alone. In an era when most believed in “gentlemanly warfare,” Churchill set up the Special Operations Executive – a covert group who worked in enemy territory to (in Churchill’s words) “Set Europe ablaze.”

He also worked hard to draw a fanatically neutral America into the war. It was thanks to him that Britain and the US share the current “special relationship” they do. And being Churchill, he had to threaten that, as well.

After WWII, America, Britain, and the USSR bathed in the warm afterglow of victory. Churchill visited the US and on March 5, 1946 gave a speech meant to make that “special relationship” even more so.

Then he spoke of the Soviet threat and warned of the coming “Iron Curtain.” Since Americans and Britons still thought of the Russians as allies, they weren’t exactly happy with his message. Today, historians mark the official start of the Cold War with that speech.

Churchill was a man of many contradictions. He was a war hero, politician, writer, artist, and largely responsible for Britain’s refusal to submit to Nazi Germany.

He also opposed Indian and Irish independence, did nothing as millions died during the Bengal Famine of 1943, proposed using poison gas to quell rebellion, and thought that Africans and Amerindians were meant to give way to Europeans. And that’s just the tip of the iceberg.

Yet Churchill was a product of his time. More importantly, he became the one whom Britain and the rest of non-Germanic Europe needed most during WWII. He was, therefore, the greatest Briton, and like all great men, he made great mistakes.