The War in the Pacific was perhaps the last time that history has given us all-out open warfare between two mighty naval fleets on a global scale. Yes, there have been Naval engagements since, ships lost, and men sent to the bottom.

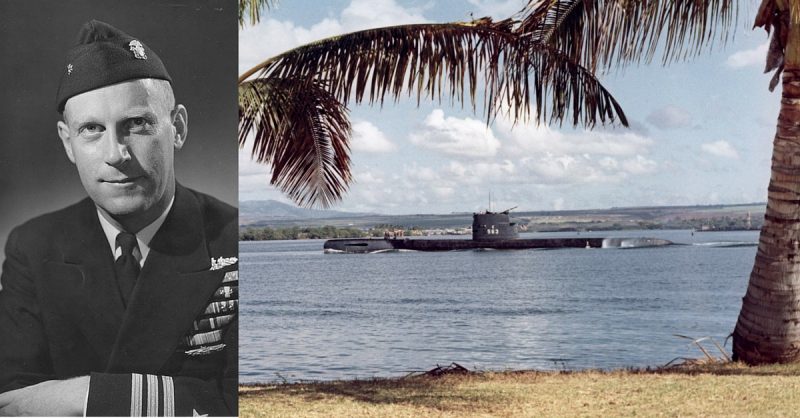

But with the Japanese and American navies using every ship that could float to try to kill one another throughout the Pacific is something hard to conceptualize today. And for the America fleet, few men did it better than Commander Richard O’ Kane.

Credited with taking out over 30 Japanese ships before his own submarine was sunk in late 1944, this future Medal of Honor recipient brilliantly and boldly took the fight to the Japanese in waters they claimed superiority. For until the day he was captured and made a POW, if O’Kane and his USS Tang were in the water, some Japanese would soon be swimming.

Born for Life at Sea

Richard O’Kane was born in 1911 Dover, New Hampshire. Recognizing his calling to serve at sea, he attended the US Naval Academy in Annapolis and graduated in 1934. He initially served aboard the heavy cruiser Chester and the destroyer Pruitt. However, his future would be with those who dwell beneath the surface and after submarine instruction in 1938, he was assigned the USS Argonaut. This would be his new home until 1942 when the Argonaut, a sub commissioned in 1928 was put in to be overhauled.

With the war in the Pacific now in full swing, Lieutenant Commander O’Kane joined the new submarine Wahoo as her Executive Officer. He would serve under Commander Dudley “Mush” Morton, who was just four years ahead of him at the Naval Academy but commanded his own submarine.

Together, they would perfect the art of the submarine attack. The Wahoo would become one of the most celebrated ships World War 2 as it racked up 19 Japanese ships sunk.

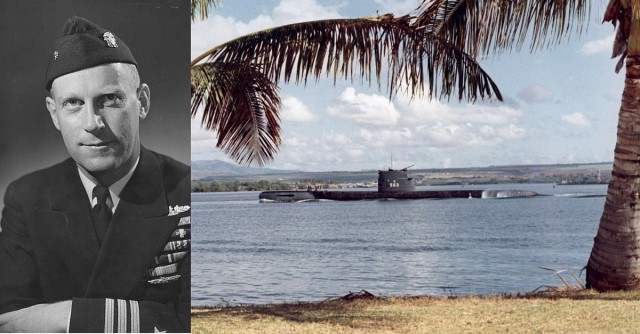

Fortunately for O’Kane, he was given command of his own sub in 1943 when he took the helm of the USS Tang. Meanwhile, the Wahoo would go on to disappear at sea never to be heard from again and presumably lost in combat.

But the USS Tang still had a great deal of fighting ahead of them and together, O’Kane and the USS Tang would make history together.

Mastering the Art of the Submarine Warfare

For a submarine commander, he had a responsibility to take the fight to the enemy often in very contested waters. O’Kane and the USS Tang would make five war patrols into enemy territory attacking Japanese ships and performing “Lifeguard Duty” where a submarine would be placed off the coast of an enemy island under air attack in order to rescue any down pilots that might have to ditch their planes.

During one such lifeguard session off the island of Truk, the USS Tang would rescue 22 airmen in one mission earning them a Presidential Unit Citation.

However, it would be sinking ships not rescuing men that would become his claim to fame. The records of how many ships sunk have regularly been in question as post-war Japanese records were examined to confirm or add to American accounts.

Officially during their 5 war patrols, the USS Tang led by O’Kane was credited with 24 Japanese ships sunk would make the Tang the second highest total for an American Submarine and Lieutenant Commander Richard O’ Kane, the highest for a single commanding officer. Other reports using Japanese records could put the total as high as 31.

O’Kane would make dashing in and out of enemy convoys seem easy as they constantly scored wins navigating the submarine through the burning heaps of floating metal that they created.

Unfortunately, O’Kane’s remarkable run would come to an end in late October of 1944 when it is believed that one of their own torpedoes malfunctioned and made a circular run striking the USS Tang and killing all be 8 of its 87 man crew.

O’Kane was one of the fortunate that made it out alive, but the only people conducting “lifeguard duty” in these waters were the Japanese as O’Kane and the surviving crew were “rescued” by an agitated Japanese crew none too happy about what O’Kane had just been doing to them.

Time as a POW

For Richard O’Kane and the surviving crew, they would have to sit out the rest of the war a Japanese prison camp near Tokyo where they would endure beatings and starvation for the next 10 months before the war would end.

Upon his release, Richard O’Kane was awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions aboard the USS Tang before it sunk. And there are few better ways to recount such a fascinating tale than to take it directly from the Medal of Honor citation. It reads:

For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty as commanding officer of the U.S.S. Tang operating against 2 enemy Japanese convoys on 23 October and 24 October 1944, during her fifth and last war patrol.

Boldly maneuvering on the surface into the midst of a heavily escorted convoy, CMDR O’Kane stood in the fusillade of bullets and shells from all directions to launch smashing hits on 3 tankers, coolly swung his ship to fire at a freighter and, in a split-second decision, shot out of the path of an onrushing transport, missing it by inches. Boxed in by blazing tankers, a freighter, transport, and several destroyers, he blasted 2 of the targets with his remaining torpedoes and, with pyrotechnics bursting on all sides, cleared the area.

Twenty-four hours later, he again made contact with a heavily escorted convoy steaming to support the Leyte campaign with reinforcements and supplies and with crated planes piled high on each unit. In defiance of the enemy’s relentless fire, he closed the concentration of ship and in quick succession sent 2 torpedoes each into the first and second transports and an adjacent tanker, finding his mark with each torpedo in a series of violent explosions at less than 1,000-yard range.

With ships bearing down from all sides, he charged the enemy at high speed, exploding the tanker in a burst of flame, smashing the transport dead in the water, and blasting the destroyer with a mighty roar which rocked the Tang from stem to stern.

Expending his last two torpedoes into the remnants of a once powerful convoy before his own ship went down, Comdr. O’Kane, aided by his gallant command, achieved an illustrious record of heroism in combat, enhancing the finest traditions of the U.S. Naval Service.

After the war, Richard O’Kane would remain in the Navy rising to the rank of Rear Admiral. He passed away in 1994 and is buried at Arlington National Cemetery. A Medal of Honor recipient and not to mention the 3 Navy Crosses, he is one of the most highly decorated sub-commanders of the Pacific.

It is unclear when or if history will allow us to see such a mighty Naval engagement take place again, but any participants would do well to hope that men like Richard O’Kane were aboard to lead the way.