Sometimes, things aren’t always so black and white. Take the Nazi officer who ran a concentration camp in Poland. Who would ever have thought that he’d be recognized as a hero among Jews?

That man was Wilhelm Adalbert Hosenfeld, born on May 2, 1895 in Mackenzell, Hesse-Nassau, Prussia – then a part of the German Empire. A devout Catholic, he was active in Catholic Action – lay Catholics who wanted a Germany that was more… well, Catholic.

He was also a patriot, which was why he served in WWI. They gave him an Iron Cross Second Class for that – given only to those who performed an impressive act of bravery, or who did something above and beyond the call of duty.

It was all well and good till he chose the wrong side in 1935. After its loss in WWI, Germany was both broke and fractured as different factions vied for control of the country. One of these was the National Socialist German Worker’s Party (NSDAP) – better known today as the Nazi Party.

Hosenfeld kept a meticulous diary of those years. Collated and recently published in German by Hermann Vinke (a radio journalist and author) as “I Always See the Human Before Me,” the English version isn’t yet available, but what it reveals is fascinating.

Hosenfeld had idolized Hitler and believed in the Thousand-Year Reich – a Golden Age for Germany and its people. Given how poor the country was and getting more so with the reparations they had to pay, it made perfect sense.

Under the new leadership, Germany was recovering from its economic slump and life was improving for ordinary Germans. But at a terrible price.

Hosenfeld’s diaries and letters to his wife showed his growing disillusionment with Hitler and with Nazism. He would see the full extent of it when he was drafted into the Wehrmacht (German military) in August 1939.

Stationed in Poland the following month, what he saw there disgusted him. In a letter to his wife, he claimed, “What cowards we are… For this, we will be punished and later our innocent children too. With the mass-murder of the Jews, we have lost this war… We have no right to mercy or compassion.”

Hosenfeld was transferred to Warsaw in July 1940 – part of the Guard Battalion 660 as a staff officer and battalion sports officer. Against regulations, he attended Catholic mass in local churches. His next step was to save those he could by giving them a job at the sports stadium he supervised, or release papers so they could get out of jail.

Among these was Leon Warm, a Jew who escaped from a train bound for the Treblinka concentration camp in 1942. Warm returned to Warsaw and survived because Hosenfeld gave him a false identity and work at his stadium.

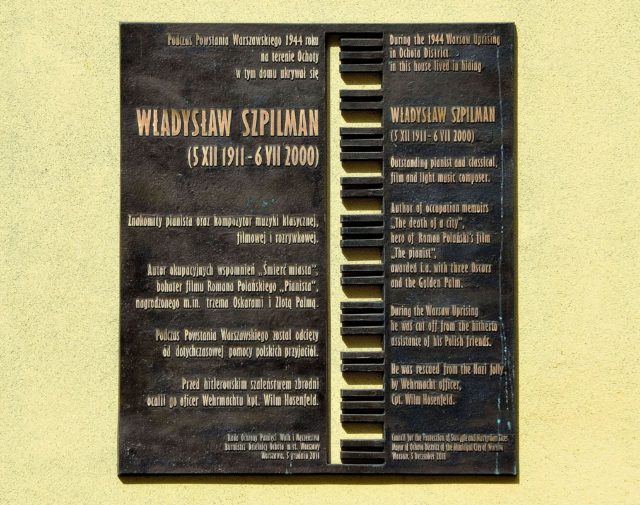

Based on Warm’s testimony and others, it’s believed that Hosenfeld may have saved over 60 Jews and some non-Jews from extermination. The most famous person he saved, however, was Władysław Szpilman (pronounced Vu-wa-dis-waf Shpeel-man) – a Polish celebrity pianist and composer.

On the morning of September 23, 1939 Szpilman was at the Polish Radio building in Warsaw playing Frederick Chopin’s “Nocturne in C-sharp minor.” The first German bomb reached the city before he was halfway through, blasting a hole through the station and ending his broadcast.

Szpilman survived, but his nightmare would begin for he was a Jew. His story was portrayed by Roman Polanski’s 2002 movie, “The Pianist,” starring Adrien Brody as Szpilman.

After his family were loaded onto the trains, the composer stayed on in the city as a worker. He later helped in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising (April 19 to May 16, 1943) when Jews fought back – the single biggest Jewish resistance in WWII.

It was doomed from the start, resulting in the destruction of the ghetto and the deportation of all its Jews. Szpilman survived with the help of non-Jewish friends, but couldn’t stay with them lest he put them at risk.

He therefore found shelter in ruined and abandoned buildings. Sometime in August 1944, he was at an empty manor house on Aleja Niepodległości 223 (Independence Avenue) when Hosenfeld found him – emaciated and barely alive.

The officer asked Szpilman to play something for him on the ground floor piano. The Jew complied by playing Chopin’s “Ballade in G minor.” Hosenfeld brought him regular supplies of food, after that, as well as a coat to survive the freezing winter with.

Other than that, there wasn’t much talk between them. In another letter to his wife, Hosenfeld expressed his shame at being both German and a member of its military. As such, Szpilman never knew the name of the man who helped him survive the final year of the war.

In gratitude, he told the German officer his name, vowing to do whatever he could for him if he ever had the chance. When Poland was liberated, Szpilman went back on Polish radio and finished the concerto the Germans interrupted.

Hosenfeld was caught by the Soviets at Błonie (bwon-ye), west of Warsaw, where he was arrested along with his men. He was charged with spying and sentenced to 25 years of hard labor. The following year, he was allowed to send a letter to his wife.

In it was a list of Jewish names he had saved – including Warm and Szpilman. What he didn’t know was that the pianist was also looking for him.

Since he didn’t know Hosenfeld’s name, Szpilman wrote “The Death of a City,” published in 1946. He described not only what he went through, but also how a German officer had been kind to him. This became the basis of the book, “The Pianist,” on which the movie was based.

Szpilman wouldn’t know the truth till 1950, but could do nothing for Hosenfeld in a Soviet Poland. So the latter died in a Soviet prison on August 13, 1952 – very likely from torture.

It was Szpilman’s son, Andrzej, who asked the Yad Vashem (Israel’s Holocaust memorial) to recognize Hosenfeld as one of the “Righteous Among the Nations.” They did so on November 25, 2008.

And that’s why Vinke titled his book as he did – to show that people are more than just labels or groups.