This being the bicentenary year of the Battle of Waterloo there is an increased interest in all things Napoleonic. There is a lot to read on the subject and I have dabbled over the years with accounts of the battle and I’ve also read the Letters of Private Wheeler, which I can recommend. I watched a lot of Sharpe on the telly but never read the books. The war in Russia remains something of a mystery to me, it was never on my radar and I suppose my only exposure to it would be the battle scene in War & Peace, another of those books everyone has heard of but not many get round to reading. I only know it through a BBC television adaptation from a lifetime ago. I use these examples of real history becoming cultural references because they help us identify with events, if only for the most slender of reasons, and I hope they illustrate that I don’t pretend to be more widely read than I actually am.

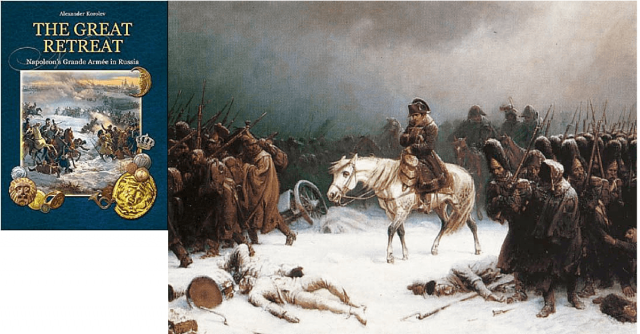

This book by Alexander Korolev reads like a catalogue or roll call of the Grand Armée. The author lists all the units that took part on the side of Napoleon and with this we get to see an array of artefacts found on the route of the disastrous retreat from Moscow across Russia, into modern day Belarus and the Baltic States before reaching nominal safety. Just under half a million men invaded Russia and only 80,000 came out alive. To describe it as a disaster would be an understatement.

Napoleon is always listed as a great tactician – a genius for warfare, but sometimes this does not stand up very well to scrutiny. His modus operandi was to have his armies live off the land, taking what they wanted how they wanted en route to his many victories; but he gave little or no thought to how that would work in reverse. The Retreat from Moscow subjected his army to the vengeful attention of all the places it had passed through en route and this added considerably to the horrors of retreat for men crippled by the weather and hunger on top of any combat injuries they may have endured.

There is a brief description at the start of the book where the author explains how many of the artefacts were found on the sites of camps during the retreat, or where parties of troops were ambushed by furious locals along the way. We learn a little about how the collapse of the Soviet Union allowed what appears to be a bout of metal detector led anarchy before the new Russian regime imposed order on the new archaeology. I suppose it draws an analogy with the frequent images showing the lost effects of that other deluded army that invaded Russia just seventy odd years ago. I’ve been at events where piles of rusty German helmets and bits of equipment have been on sale. I made a reference to Henry Ford and the often misquoted History is bunk in a previous review and feel bound to revisit it. If ever there was proof that Ford’s view is nonsense you only have to ask the ghosts of Hitler and his Nazis why they didn’t bother reading any.

Mr Korolev has brought together a genuinely amazing collection of images and information. He knows his stuff. The illustrations of buttons, bits of headdress and other accoutrements are really quite fascinating. Colour artwork of the uniforms of the Grand Armée adds to the effect and the book enjoys something of an encyclopaedic feel about it.

There is a marvellous photo of an ancient gentleman, Victor Louis Baillot, who died in 1898 and was the last survivor of a French infantry regiment that had marched to Moscow in 1812. The dignified old chap was awarded a Légiond’honneur late in life showing how that refreshingly correct manner of French gratitude towards war veterans that we saw with the last Great War survivors and now men from World War II was alive and well over a century ago. More importantly the photograph makes the men of 1812 much more real to me, and not just quirky lithographs.

What the book doesn’t do is show us anything of the Russians who took on a huge almost pan-European army and defeated it using flesh and blood, the weather and just about anything else useful to achieve success. But this is not the point of the book and I mention it as a way of encouragement to find other sources to achieve parity of knowledge.

I like this book because I love all the archaeological stuff – bits of brass, sword scabbards, buckles and buttons. They bring a one-dimensional war to life and I can easily make comparisons with the bits and pieces I have found on the Somme, in Flanders and at Gallipoli. Bringing this all together into what, as I said, feels like a catalogue of Napoleonic folly, is a genuine achievement for Mr Korolev. I am not a student of the Napoleonic Wars but I am glad to have seen his book for all the reasons I have given. Genuine enthusiasts will lap it up.

The translation by Paul Williams made from the Russian original published by Likki Rossi is well managed and the style and look of the thing is genuinely appealing. There is nothing I can find to say against this book. It really works for me.

Reviewed by Mark Barnes for War History Online.

THE GREAT RETREAT

Napoleon’s Grand Armée in Russia

By Alexander Korolev

Uniform Press

ISBN: 978-1-90650-941-5