The United States is home to one of the most controversial military bases in the world – and it’s probable you’ve never heard of it. Tonopah Test Range, nicknamed “Area 52” by veterans and conspiracy theorists, continues to be shrouded in secrecy, with little known about what, exactly, goes on there, in the Nevada desert.

During the Cold War, TTR, as it’ll be referred to from this moment on, witnessed four “dirty bomb” and over 800 underground detonations that subsequently contaminated the surrounding area, from the soil to nearby waterways.

While they didn’t know it at the time, the service members stationed there were regularly exposed to ionizing radiation as a result of these tests, with many suffering negative health effects later in life. While retired veterans are guaranteed medical care through the Department of Veterans’ Affairs (VA), the majority who served at TTR have been denied treatment.

Why? The classified nature of the work, which resulted in their records being sealed.

This lack of treatment, along with the US Department of Defense‘s refusal to release their medical records and the government’s failure to acknowledge the nature of their service, has led several TTR veterans to spearhead a campaign to force change. At the helm is Mark Ely, who himself is sick as a result of inspecting captured Soviet MiGs at the base while serving as a tactical aircraft technician (also known as a crew chief).

For many, Ely was the one to inform them of the possible connection between their health issues and service at Areas 51 and 52, and he’s determined to get them to treatment they deserve, no matter the cost.

Tonopah Test Range, today

Before we can go into the impacts serving at TTR has had on the veterans stationed there, we first need to understand just what, exactly, went (and goes) on there.

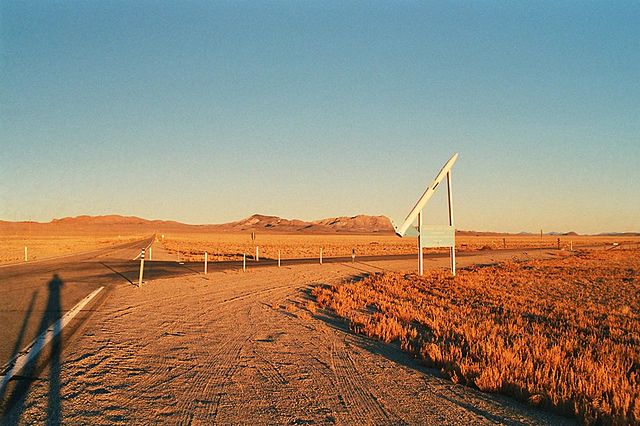

Owned by the Department of Energy and managed by Sandia National Laboratories, TTR is operated by the US Air Force. Located 60 miles northwest of Area 51, in the middle of the Nevada desert, its purpose is threefold:

- The research and development of military fusing and firing systems.

- Reliability testing of the nation’s nuclear weapons stockpile.

- Testing of nuclear weapon delivery systems.

However, its history is much more diverse and controversial.

History of Tonopah Test Range

Opened in 1940 by US President Franklin D. Roosevelt for the US Army Air Corps (USAAC), the TTR took over from Salton Seas as the site for weapons research in the mid-1950s. As aforementioned, several hundred nuclear tests and detonations took place there over the course of the Cold War – 288 detonations at Area 3 and 71 at Area 10 – with notable ones being Operations Jangle, Upshot-Knothole and Plumbbob.

What made the nuclear detonations conducted at TTR different from those seen during the likes of Operation Crossroads or even the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II is they involved “dirty bombs” – weapons containing a mixture of radioactive material (plutonium) and conventional explosives. Their sole purpose is to contaminate the surrounding area with radiation.

Speaking with War History Online, Ely explains why these weapons were developed and the science behind them. “The purpose of a dirty bomb is to spread the contamination – the plutonium – into the atmosphere and into the soil, and contaminate the soil,” he says. “The dirty bomb spreads the plutonium into the soil to contaminate it, therefore leaving the infrastructure in place.

“After killing off the biological life (humans) through radiation exposure, the military would send in a decontamination team.”

Contamination of Tonopah Test Range

As Ely explains, the purpose of “dirty bombs” is to contaminate the soil – and it did just that. In 1975, the federal government performed an assessment of TTR and found radioactive material had dispersed throughout the base and the surrounding area.

While the Department of Defense was aware of the ill-effects exposure at the site posed to the airmen stationed there, it refused to stop the testing taking place, claiming such a move would go “against the national interest.”

“We [were at] Tonopah Test Range because it was an unoccupied, as well as empty, space within the boundaries of the classified lands of the US government,” Ely explains. “The Department of Energy was detonating ‘dirty bombs,’ as well as below- and aboveground nuclear bombs, into the environment on purpose. That was their job. Simply put, a conventional atomic bomb destroys the target in the initial blast, whereas a ‘dirty bomb’ contaminates the target and kills the humans over a period of time.

“The ‘dirty bombs’ had 6,200 pounds of plutonium as [their] payload, which was spread into the environment. The plutonium went into the soil, [creating] more coarse, bigger molecules of plutonium. That fuses to become plutonium silicate, which is unstable, and unstable plutonium is sticky. Imagine taking a little fuzzy cotton ball, dipping it in glue and then throwing it on the ground. It’s going to stick and bind to the ground.

“That means when you have an unstable plutonium silicate, it binds to the environment, and it becomes permanently part of that environment,” he continues.

According to Ely, the compound’s ability to bind to the environment makes cleanup efforts incredibly difficult, not that any such actions were taken during his time at TTR.

“There was absolutely no cleanup done whatsoever while we were on the range, and I was there from 1985-89,” he says. “The very first cleanup that was actually done was done in 1992, and then there was a second [one] done in 1996 by the Department of Energy, [the] Water Resources Center of Nevada, [the] Desert Research Institute of Nevada, and [the] University and Community College System of Nevada.”

Subsequent investigations over the years have found continued contamination at TTR, and while government employees who were stationed there during the Cold War have received $25.7 billion in federal assistance, military veterans have yet to receive such compensation, due to the classified nature of their assignments.

Even those not involved in nuclear testing have been impacted

Along with the detonation of “dirty bombs,” TTR was also responsible for the testing of foreign surface-to-air missiles (SAM) systems, such as the Soviet S-300PS, and flying the Lockheed F-117 Nighthawk, the Air Force’s top-secret stealth attack aircraft.

As hinted at by Ely’s work as a crew chief, Soviet MiGs were examined and flown at the base. In fact, TTR was home to Constant Peg, the MiG air combat training program conducted by the 4477th Test & Evaluation Squadron “Red Eagles” from 1979-88. Developed by Silver Star recipient and Vietnam veteran Col. Gail Peck, it taught some 5,930 American airmen how to operate and fly against enemy aircraft.

At the time, the MiGs were being flown out of Area 51. The Department of Defense wanted another area from which they could be examined and commissioned Col. Peck to find a new location. He chose TTR, with Ely noting the storied pilot was unaware at the time that the site had been contaminated by the aforementioned detonations.

“We were able to use the Secretary of Defense’s military construction fund, and then money that had already been appropriated, so we had this conduct of money that was basically set up,” Col. Peck tells War History Online regarding how the airstrip at TTR came to be.

During the Cold War, technology was nowhere near as advanced as it is today, meaning there was a lack of monitoring equipment available to check how much radiation airmen stationed at TTR were being exposed to, either directly or indirectly, on a daily basis. That being said, the Department of Defense was aware of the extent of the contamination, but assured those stationed there that they had nothing to be concerned about.

As has become glaringly evident, this was far from the truth.

Among the pilots to fly with the Red Eagles was CJ “Heater” Heatley III, who, along with being a pilot, was the one to create the squadron’s insignia. Also a former TOPGUN instructor in the US Navy, he explains that he began to suffer from ill-health during his service, with him showing signs of lymphoma during the mid-1980s.

“I was anemic in 1984 and ’85, which was the first symptom of cancer. So I was grounded a few times and they couldn’t figure out what was causing it because lymphoma was so rare,” Heatley tells War History Online, adding he received the diagnosis of a rare form of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma from the Mayo Clinic.

“No one in my family has it. No one in my extended family has it. So I’m pretty sure I picked it up in Area 52,” he surmises, adding, “Nobody told us that the area was full of plutonium and lithium all over the place.”

Jim Bell, a retired crew chief who served with the Red Eagles and was back and forth between TTR and Area 51 for about 10 years, says he’s been diagnosed with lung disease, adding that the Department of Defense “never told us anything” regarding the risk of radiation exposure.

Putting two and two together

For many of the veterans who served at TTR, the knowledge that their health issues may be related to their military service didn’t come about until they heard from Ely; those interviewed for this piece learned of their radiation exposure during a call with him.

“Mark told me, and he showed me a thing on the internet [that said] ‘dirty bombs’ were tested up there. They never told us that,” Bell tells War History Online. “I used to drive through the plutonium fields just about daily, to get in and out, to go over to Area 51 and come back into our area.

“So I was constantly driving into it or walking into it, drinking the water, taking showers. It affected me, and I think it affected two of my children.”

Upon learning about the radiation exposure, Ely purchased a geiger counter (a device that measures radiation) off of eBay and traveled to Holloman Air Force Base, New Mexico, where one of the aircraft he worked on is on-display. He found it still shows signs of being contaminated with plutonium.

He then set to work gathering the stories of retired Air Force airmen who’d previously been stationed at TTR and informing them of the connection. He was the one to inform Col. Peck of the situation; the pilot had not only been exposed to radiation at Area 52, but also Agent Orange during his Vietnam-era service. This, paired with the high g-forces he experienced while a fighter-pilot, led to cirrhosis of the liver, which is only compounded by the impacts of his later service.

“I came down with prostate cancer,” Col. Peck explains. “Had to have my prostate removed at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas, which has been a significant change in my quality of life. […] That’s what I had to do to stay alive.

“Some of the other [problems] are just superficial,” he continues. “The Schambergs on my ankles, which came back and I’m still treating it. It’s still a bit of a problem for me.”

Ely adds that Col. Peck’s wife, Peg, died of cancer, which he believes is related to the pilot’s service at TTR. “He brought it home when he was out on the range,” Ely shares. “He was out on the range in the period and explosions were occurring right near him. […] The exposure that he was getting on his uniform, he was taking home to his family, and he didn’t know that.”

Impact on more than just veterans

As Ely and Bell bring up, the exposure suffered by the airmen stationed at TTR didn’t just impact them – it had an effect on their families, as well. The radiation they brought home on their uniforms resulted in cross-contamination when they were taken off and put in the wash.

Outside of the direct health impacts experienced by the loved ones of these veterans, it’s important to note the mental and emotional toll all this has had on those involved.

Emilio “Sandman” Sandoval, who worked supply with the Red Eagles, has been candid about how his diagnosis and health issues have impacted his family. In 2014, after developing several tumors, he was given 10 years to live, something that was difficult for him and his family to swallow.

“Nobody told us we were radiated from downwinders or that the water got contaminated,” he explains. “A lot of things that happened because [of] one, two gamma rays. […] You feel it when you feel that your body’s not working right at that moment.”

He’s since had time to come to terms with his terminal diagnosis, and as the 10 year mark approaches, he’s determined to keep on going. However, he’s had to prepare his family for the worst case scenario.

“I’m not afraid to die, whenever that happens” he tells War History Online. “I told my brother, my mom and my father, my kids […] when it’s my time, there’s a song [‘November Rain’ by Guns N’ Roses] I want [them] to play. I don’t want nobody to cry; it was my time.”

Poor treatment by the Department of Veterans’ Affairs

As aforementioned, the majority of veterans who served at TTR have received little-to-no treatment from the VA, despite it being their right as honorably discharged service members. Most have been given “come back in X months and we’ll see if it’s gotten worse”-type of treatment, with others being outright denied, as they’re unable to prove their conditions are a direct result of their military service, given their records are classified.

Rick Workman, a nuclear weapons technician and commander of the F-117A Nighthawk who spent about nine months at TTR before being deployed overseas for the final stages of Operation Desert Storm, was never made aware that he and the men he was in charge of were being exposed to radiation. Now, he’s in a fight to change how he and other veterans are treated by the VA.

“That secrecy has been a tool used by the VA and the Department of Defense for all these decades,” he explains, with Heatley echoing these sentiments, saying the VA has been no help in his case. He’s since been diagnosed with amyloidosis, which he believes piggybacked off his lymphoma.

“I was just so tired and fatigued. I couldn’t do anything,” he explains. “I was very athletic and active and did competitive sports, and it was like, overnight, I couldn’t do it anymore.”

Heatley was given a few years to live, unless he went on a specific medication that’s particularly pricey. When the VA failed to offer up any help, his friends set up GoFundMe campaigns to help pay his hundreds of thousands of dollars in medical costs.

“I gave up on the VA,” he shares. “It’s just too hard, too bureaucratic. They don’t seem to care. The doctors don’t seem to care. […] They don’t have the familiarity or expertise to help anyone. Instead of saying it, they just shuffle you around and treat symptoms. They don’t treat the disease.”

Bell’s been stuck battling this bureaucracy, too, saying that, despite him explicitly giving the VA permission to access his records, he’s been given the runaround.

“I’ve signed all kinds of papers for the VA to tell them they could take my records,” he says. “They have the right to go back into the Pentagon. They can pull our records, as long as we sign the paperwork saying that they can take our records, and they just keep sending me the same paperwork over and over and over.”

Things have gotten so bad that Bell has even enlisted the help of his congressman, only for him to be given the same treatment. “He’s getting the same runaround as I will get,” he reveals.

Sandoval, like Heatley, has also had to pay out of pocket for his treatment, which he admits “not anybody can do.” He himself had to borrow money from his parents, with him explaining that the VA will cover conditions related to his “wartime experience,” but not the radiation he needs to keep his tumors in check.

He’s continued to question why he and his fellow veterans have been treated so poorly, while employees with the Department of Energy have received compensation. He asks, “Is it one thing that happened to make the Department of Defense not take care of us? Why? What’s the difference? What is the difference, whether a contractor or DoD or super secret projects? What is it?”

Sound of Silence Project

Rick Workman, upon learning about the poor treatment these veterans continue to face, did his own research into conditions caused by radiation exposure, aware many of the men he’d served with over the years have since been diagnosed with various cancers and other diseases.

“I was basically sick and tired of hearing about so many nuclear weapons technicians [who] I had worked with, worked for in some cases, [who] just suddenly started getting sick,” he explains. “Everybody gets sick – well, not everybody – lots of people get sick as we age and that’s the excuse I heard from so many veterans, ‘Well, yeah, I don’t think it’s related to radiation because we all get sick and die eventually.’

“But it’s the ones that I had heard about, a lot of these guys were multiple diseases, multiple cancers, and either suffered for many, many years and never got better. […] I started researching what diseases can be caused by radiation; that’s my first assumption, radiation.

“What I learned is that we were being bombarded, and that kind of provided a potential explanation for so many different types of illnesses and so many sudden illnesses,” he continues.

This, paired with the stories he’s heard from veterans regarding their experiences with the VA, has led Workman to spearhead the Sound of Silence Project, which aims to force the VA to provide benefits to former nuclear weapons technicians who were exposed to toxic chemicals and radiation through their work during the Cold War.

“I started learning that so many veterans have been applying for benefits through the VA Business Administration, and they almost exclusively denied,” he explained.

Under Title 38 of the US Code of Veterans’ Benefits, nuclear weapons technicians didn’t perform “Radiation-Risk Activity,” meaning they aren’t considered “Radiation-Exposed Veterans.” This is largely due to the top-secret nature of their positions.

“The VA doesn’t recognize nuclear weapons technicians, who now we know were bombarded with nuclear weapons, with radiated weapons 24/7,” he said. “The VA obviously knows that, but they won’t recognize it because the law does not consider us as being radiation exposed veterans. Therefore, they will not recognize that we had any radiation exposure whatsoever.”

The aim of the Sound of Silence Project is to have the US Congress support the proposed draft bill “Cold War Veteran Nuclear Weapons Technician Ionizing Radiation and Toxic Exposure Act,” which would connect these veterans’ service with exposure to ionizing radiation and toxic chemicals, thus allowing them access the necessary benefits through the VA.

Call for action

Bell has a message for the Department of Defense, the VA and the federal government.

“Finally acknowledge that we were there. Take care of us. Take care of our families,” he says. “They’ve already taken care of the civilians that worked up there. They paid them off to shut their mouths. But us, they just won’t recognize that we were there.”

Workman echoes these sentiments on behalf of those he’s encountered through his work on the Sound of Silence Project.

“I just want formal recognition that they know who the hell we are, that’s what a lot of people have said, because they’re past the point where they believe anything is going to help,” he says. “They think they’re going to die or they know they’re going to die, and they just don’t want the help from the VA so much as they just want the acknowledgement of what they did, their sacrifices [and] their families’ sacrifices.”

Anyone interested in learning more about the Sound of Silence Project can do so here, with additional information and interviews from those who served at Tonopah Test Range (TTR) available via Mark Ely’s Vimeo profile.

If this story has moved you to do so, please contact your representative in Congress to push them to support the proposed “Cold War Veteran Nuclear Weapons Technician Ionizing Radiation and Toxic Exposure Act” and keep pressure on the government to change how they’re treating these veterans.

More from us: Battle of Palmdale: When a Runaway Drone Wreaked Havoc In the Skies Over California

Want War History Online‘s content sent directly to your inbox? Sign up for our newsletter here!

A special thank you to Mark Ely, Gail Peck, Jim Bell, CJ Heatley, Rick Workman and Emilio Sandoval for sitting down to speak about this issue.