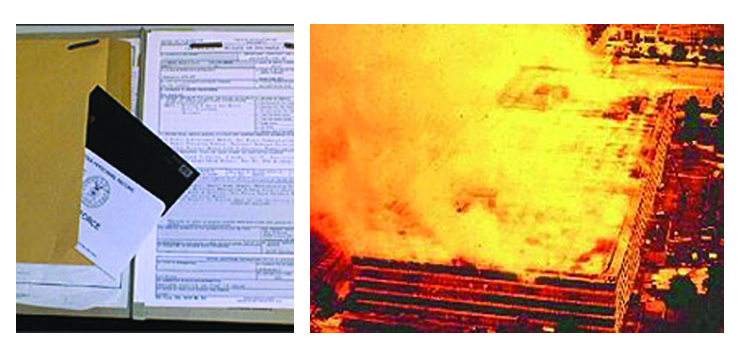

The National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) on the outskirts of St. Louis caught fire on July 12th, 1973. No one knows what began the blaze, but the lack of a sprinkler system and thousands of paper files contributed to a four-and-a-half day fire. It’s considered the worst archival disaster in U.S. history.

In the end, 16-18 million veterans lost their records. This includes an estimated 80% of Army personnel discharged between 1912 and 1960 and 75% of Air Force personnel whose service ended between 1947 and 1964. About 6.5 million documents were saved. Since the disaster, the NPRC has worked hard to help veterans and their families recreate the service records which were lost in the fire.

Charles Cohen didn’t realize that his records were among those destroyed until he tried to obtain a plot in the Beverly National Cemetery in New Jersey. Cohen wants to be buried next to his father, who served in the Army during World War I. That’s when Cohen learned he would need his service records in order to get the plot and that those records were destroyed in the 1973 fire.

Cohen filed a request with the NPRC and received a certificate of military service. But the certificate stated that he entered the Army and left it on the same day, April 24, 1946. It also states that he never rose above the rank of private. Cohen says that he left World War II as a First Sergeant and the Korean War as an Acting Company Commander. The certificate states that date of birth is “not available”.

“I think they just put that down because they didn’t want to go looking for anything else,” Cohen said. He didn’t understand how this could be his new military record, due to the inaccuracies.

Emil Limpert is a World War II veteran who earned a Purple Heart but who was denied benefits because his records were lost in that fire. Limpert is 90 and only applying for benefits at this time because he is “down to nothing”. After finding out that there is no record of his service, a GoFundMe fund was set up to support him financially while he continues to try to prove his military record.

The NPRC handles 5,000 requests each day from veterans or their next of kin who are seeking benefits, burial services, or answers to questions about the past. There are 25 people at the facility devoted to preserving the 6.5 million records that survived the fire and 40 people handling incoming requests.

In most cases, the NPRC is able to get information from other government agencies and veteran groups for proof of service. If they can pinpoint a date of entry or discharge, they can issue an official document like the one sent to Cohen. If they can’t find any information then it’s the end of the road for the veteran. It’s as if they never served.

Cohen can use the certificate he received for military benefits, including burial rights. Cohen feels insulted, though. He said, “I want credit for everything I did.”

Cohen says he was a member of the 609th Transportation Company, an all-black unit, in World War II. He watched friends get sick in Japan from radiation poisoning when they weren’t warned of the danger by the U.S. military. In the Korean War, he served as part of the US Army Corp of Engineers. He experienced racism while he served but doesn’t like to talk about it.