By Jeremy P. Amick

During the height of the Cold War in the 1960s, many men and women volunteered to serve the United States by donning a military uniform, never suspecting that the duties they were peforming would potentially earn them the desgination as a Soviet target.

But in later years, as information became declassified and the plans of special operational groups such as the Soviet Spetsnaz troops to target U.S. military sites was identified, many Cold War veterans have come to realize the dangers they actually lived through.

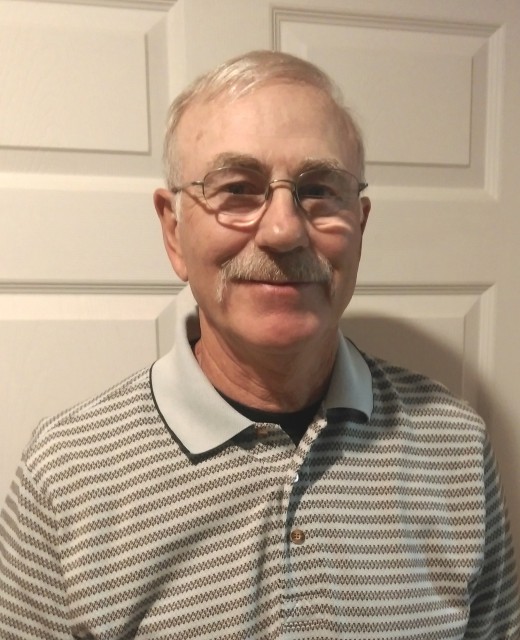

“I didn’t view myself as having done anything special … probably because I never knew that I was a target” said John Brady, 68, Jefferson City, Mo., when speaking of his time spent in the Air Force several decades ago.

A native of Iowa and the son of a civilian flight instructor, Brady was exposed to airplanes at an early age, which, he said, infuenced his decision to enlist in Air Force in the spring of 1965, less than a year after graduating from high school.

“I guess I had to have something to do because you can’t live with your parents forever,” he grinned.

Following his enlistment, he completed bootcamp at Lackland Air Force Base (AFB) in San Antonio, Texas, and transferred to Keesler AFB in May of 1965 for 44-weeks of advanced training as a digital data processing repairman.

“First off, we we were trained on binary arithmetic because computers speak in ones and zeros,” Brady explained. “Then, I learned basic electronics and was introduced to the equipment I would be working on,” including the computer systems used to process information received from radar equipment, he said.

While still in his technical training at Keesler, the young airman wedded Margie, his high school sweetheart, who then accompanied him to his first duty assignment at an Air Force radar site near Finland, Minn., in May of 1966.

Brady said, “They called it a semi-remote assignment and it was really a small base. The equipment that I was working with had vacuum tubes and would actually heat the block building that I worked in.”

As a radar site, Brady added, the base was positioned on a hilltop since radars operated through line of site. Throughout the United States, many of these sites had overlapping lines of radar coverage in an effort to identify a potential incursion of Russian aircraft.

Brady and his fellow airmen never experienced an actual Russian air attack, but they did encounter an unidentified flying object that remains shrouded in mystery.

“We received reports of a visual sighting of lights in the sky and our direction center picked up and processed a valid target on radar,” said Brady. “About the time I got off of my shift, I heard the jets scramble out of Duluth to go investigate the object.”

He continued: “When the jets got close, the pilots saw the object take off and there was a visible streak across the sky. Our radar made a 12-second revolution and reached about 200 nautical miles; so when the math was done, the object had to have been moving nearly 24,000 miles per hour.

“It wasn’t swamp gas,” he concluded, “… and we had both visual and radar contact with the object.”

In late 1967, the airman was reassigned to another radar site at Hutchinson, Kan., performing the same type of radar maintenance and repair that he had done while stationed in Minnesota.

The following year, the Air Force began scaling back the number of radar sites in the United States and Brady spent several months removing and shipping radar equimpent from the base.

After receiving his discharge in late 1968, the Cold War veteran remained in Hutchinson working for several local companies including the Cessna Corporation, working in the company’s fluid power division and applying many of the skills he acquired in the Air Force.

While living in Kansas, he and his wife became the parents of two daughters, Jill and Kelli. Several years later, he relocated to Waterloo, Iowa, and worked for the John Deere Corporation until he was laid off in the early 1980s.

“That’s when I started looking for a new job and ended up in Mid-Missouri working at the Callaway Nuclear Plant,” he said, adding, “from where I retired as a electrical supervisor in 2009.”

Although he now enjoys his retirement by playing golf and shooting antique rifles, Brady notes that much of what he has recently learned about his Cold War service sheds new light on distressing events that might have been narrowly averted.

“Looking back, I guess we were a little more on the front line than it appeared to us at the time,” Brady said. “When you lived off base, you just went home at night … which was not like being in a direct combat zone.

“But it turns out what we were doing was importatnt—or at least the Russians thought so,” he continued. “But we never knew they had made plans to target us and our radar and missile sites … and we were never told.”

He concluded: “I guess nobody thought we had a need to know.”

Jeremy P. Ämick writes on behalf of the Silver Star Families of America.

Jeremy P. Ämick

Public Affairs Officer

Silver Star Families of America

www.silverstarfamilies.org http://www.silverstarfamilies.org Cell: (573) 230-7456