The mystery of how the record breaking French submarine Surcouf sunk has been debated since the day it disappeared in the Pacific, near Tahiti.

Was her and the 130-strong crew blitzed out of existence by the enemy or was something more sinister at play? Perhaps the sinking of the undersea cruiser just a terrible, terrible accident?

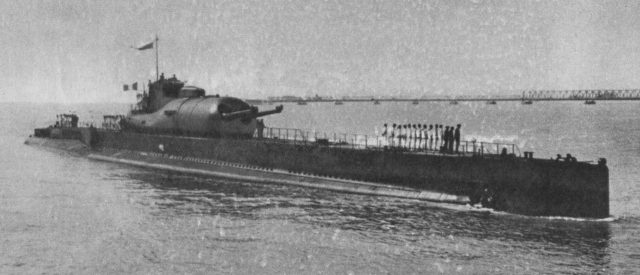

Whatever actually took place, it was a strangely fitting end to a ship that had been plagued with problems from the very start of her life until the end. Surcouf was built after the end of the First World War and was launched on the 18th of October, 1929.

It was the largest submarine ever built right up until the Japanese produced the I-400-class subs and she was named after Robert Surcouf, who made a fortune by sailing the Indian Ocean as a privateer and merchant.

The submarine was intended to be part of the trio of boats and was given the pennant number N N 3 – although the remaining two were never built and Surcouf served her time as an experimental cruiser submarine.

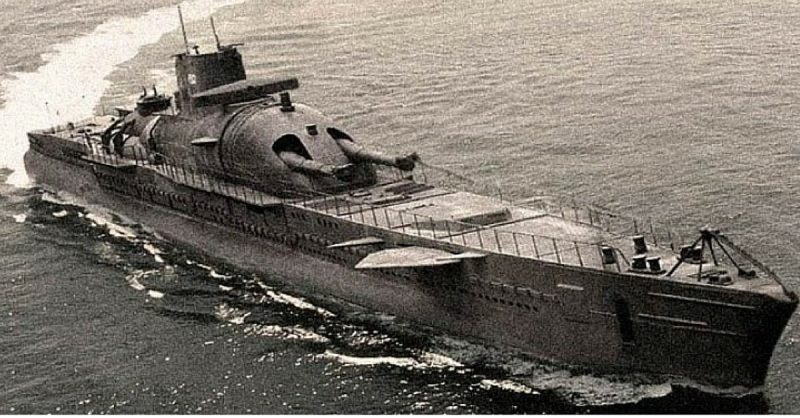

Surcouf was built to act as an underwater cruiser and was meant to seek and combat surface ships. In order to carry out reconnaissance, she was equipped with a Besson MB.411 floatplane in a hangar that was specially built near the conning tower.

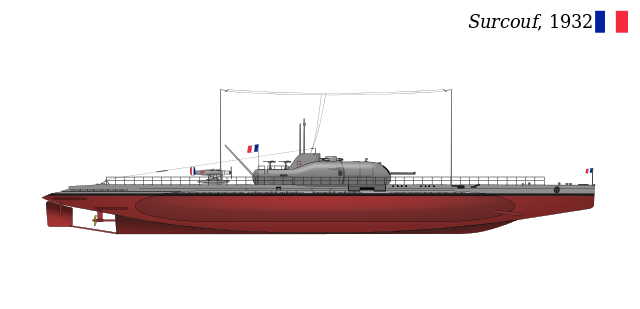

For combat purposes, she was equipped with 10 torpedo tubes. Six of them were 550mm (22 in) in diameter and four of them were 400mm (16 in). She also had two 203mm (8in) guns in a turret placed forward of the conning tower.

The 203mm was a medium naval gun that the French Navy employed and was characteristic of cruisers built because of the limitations of armaments imposed by the Washington Naval Treaty of 1922.

The 8in guns were controlled by a director who had a 5m (16ft) rangefinder that was mounted high enough to see an 11km (6.8mi) horizon. These guns were able to fire within three minutes of surfacing and if periscopes were deployed to direct fire the range to be increased to 16km (9.9mi).

As part of the original design a platform was supposed to lift a lookout 15m (49ft) into the air, but this was quickly abandoned because of the effect it would have on roll. Another way units manning the submarine could direct fire was through the Besson observation plan, which could identify targets up to the gun’s maximum range of 39km (24mi).

For defence, there were machine guns and anti-aircraft cannon mounted on the top of the hanger – and for self-preservation a 4.5m (14ft 9 in) motorboat. Included with the equipment was a cargo compartment that could also hold 40 prisoners.

The fuel tanks of the craft were also large and could contain enough fuel for a 19,000km (12,000mi) trip and had enough supplies to last the crew of 118 for 90 days.

But despite all these impressive numbers, the Surcouf run into a number of difficulties from very early on in the ship’s life. The trim was tricky to adjust during a dive and on the surface the submarine rolled badly in choppy water. She also took two minutes to dive down just 12m (39ft), which had the cruiser vulnerable to aircraft.

Along with the technical problems, the history of the ship is also murky. In 1940 the ship was based in Cherbourg, but was being refitted in Brest when the Germans invaded France.

Because the Allies didn’t want her taken, the crew was ordered to seek refuge across the channel in Plymouth. Surcouf ended up making the short journey across those dangerous seas with one engine inoperable.

On the 3rd of July came the first bloodshed the submarine would be involved in and it resulted in the needless and tragic death of three British men and one French sailor.

Because the Allies were concerned that French ships would be taken over by the German Navy, Operation Catapult was launched. This saw the Royal Navy blockade harbours that held French ships, who were given an ultimatum: rejoin the fight against the Axis powers, scuttle the ships or put themselves out of reach.

Back in Britain, the Surcouf was boarded to ensure that the ship would not fall into the wrong hands. The French took exception to his age-old foe forcing their way onto the jewel in the crown of the French Navy and a scuffle ensued.

After the dust had settled and the tempers calmed down, Cdr Denis Sprague, Lt Griffiths and LS Webb lay dead – while Yves Daniel was fatally wounded and would also pass away.

The British completed Surcouf’s refit by August 1940 and handed her over to the Free French Navy, who opposed the Vichy France regime. Tensions were still high at this point and both side accused the other of working for the Germans via the puppet regime in France. One extraordinary British claim was that the sub was attacking British ships.

After being handed over the French resistance forces, Surcouf ended up in Quebec City in December 1941. It has got there via Halifax, Nova Scotia and a three-month refit at Portsmouth New Hampshire after being damaged by a German plane while escorting trans-Atlantic convoys.

In January 1942 the Free French sent the submarine to the Pacific and re-supplied in Bermuda. This change of direction sparked rumours that Martinique was going to be taken from the Vichy for Free France.

Then all of a sudden, Surcouf was no more. After leaving on the 12th of February for the Panama Canal, communications suddenly ceased.

One theory is that she was sunk on the 18th of February 1942 after being ridden over by the American ship Thompson Lykes, which reported hitting and running down a partially submerged object.

Rear Admiral Auphan wrote in his book The French Navy In World War II that “for reasons which appear to have been primarily political, she was rammed at night in the Caribbean by an American freighter.”

Another conspiracy suggests that she was swallowed by the Bermuda Triangle or that she was caught in the act of refuelling a German U-Boat and was sunk by American forces.

Finally, the records of the 6th Heavy Bomber Group shows the sinking of a big submarine on the 19th of February. There was no German activity reported lost around that date. The clincher? The 6th was based out of Panama.