On April 5th, 1951, Judge Irving Kaufman sentenced Julius and Ethel Rosenberg to death. He called them traitors who put “into the hands of the Russians the A-bomb years before our best scientists predicted Russia would perfect the bomb.”

The jury had convicted them of conspiracy to commit espionage. In June of 1953, after nearly two years of appeals, the couple were electrocuted at Sing Sing Prison.

The Truman administration was certain that the Rosenbergs needed to die. The government stated that the Rosenbergs had passed secret information on the atomic bomb, and this allowed the Soviets to develop their own nuclear weapons.

The Soviets, newly empowered with the atomic bomb, had encouraged the North Korean invasion of South Korea in 1950. The U.S. and UN militaries stood in opposition to the invasion. The American government wanted to show that they would not tolerate any Soviet espionage, and the Rosenbergs were to be made an example of.

The American people believed their leaders and the charges against the Rosenbergs. Judge Kaufman used the administration’s charges to justify the death sentence.

In the courtroom, Judge Kaufman rationalized the sentence by arguing that espionage was “sordid, dirty work” which included “the betrayal of one’s country” and thus deserved the maximum sentence. The penalty for espionage was up to 30 years in prison or death if the crime occurred during wartime.

Since the conspiracy began during World War II, Judge Kauffman argued that the executions were justified. He intended the sentence to be a deterrent to anyone else considering betraying their country. Leniency towards the Rosenbergs would be interpreted as weakness by overseas enemies, in his opinion.

The judge admitted that though sentencing a young mother to death seemed harsh (the Rosenbergs had two young sons, Michael, and Robert), it was necessary in this case. While Julius “was the prime mover in this conspiracy,” Kaufman explained, “let no mistake be made about the role [of] his wife, Ethel Rosenberg. Instead of deterring him from pursuing his ignoble cause, she encouraged and assisted the cause.”

She was a mature woman, “almost three years older than her husband and” – despite much evidence to the contrary – “she was a full-fledged partner in this crime.”

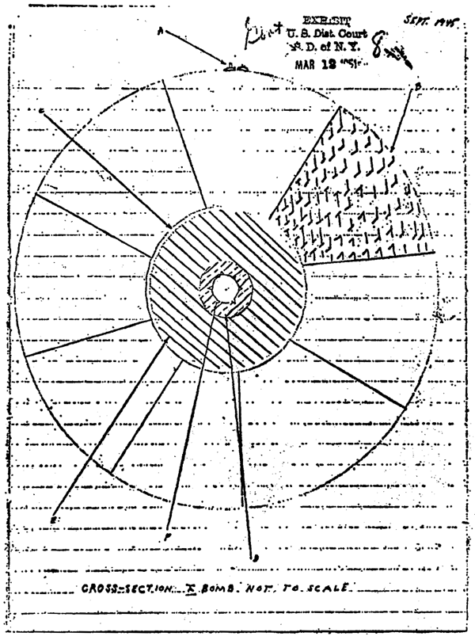

But the charges brought against the Rosenbergs have been proven false. The Rosenbergs did not give an atomic bomb to the Soviets. Julius received information from his brother-in-law, David Greenglass. Greenglass, who was an Army mechanic and did not have the training to understand the documents.

Scholars still debate the value of the documents that the Rosenbergs provided the Soviets. It is likely that there was little to no new information in the documents they provided.

Julius did run a large spy ring which sent U.S. military secrets to the Soviet Union from 1944– 1950. Judge Kaufman used this to justify the death sentences. Kaufman also conferred with the State Department, which hoped that the death penalty would scare the Rosenbergs into confessing and naming the other spies in the network.

The FBI was ready to listen until their final moments. The Rosenbergs called their bluff and took their secrets to the grave.

Historians disagree on why the North Koreans invaded South Korea, but they do agree that the Soviets had nothing to do with it. Stalin rejected North Korea’s invasion plan, even after the Soviet test of an atomic bomb, though he eventually relented after the communist victory in China.

The 1951 trial was a mess, plagued with irregularities and illegalities. Truman’s Justice Department prosecution team committed acts of misconduct, the judge violated the judicial code of ethics, the defense performed its duties with great incompetence, and the Supreme Court’s subsequent review of the case proved inadequate. After President Eisenhower twice denied them clemency, prison officials electrocuted the couple on June 19th, 1953.

The executions were harmful to the reputation of the U.S. around the world. They triggered protests in 84 cities in 48 countries around the world. Even its allies saw the executions as senseless violence caused by paranoia about the spread of Communism. Protesters accused the U.S. officials of allowing that fear to cloud their judgment.