Medal of Honor recipient Master Sgt. Roy Benavidez was the definition of a true American hero. Surviving “six hours of hell” in the jungle along the Vietnam-Cambodia border during the Vietnam War, he put his life on the line to rescue his comrades from a situation that would have otherwise proved deadly. While undeniably a selfless act a bravery deserving of the Medal of Honor, it took Benavidez over a decade to receive the decoration.

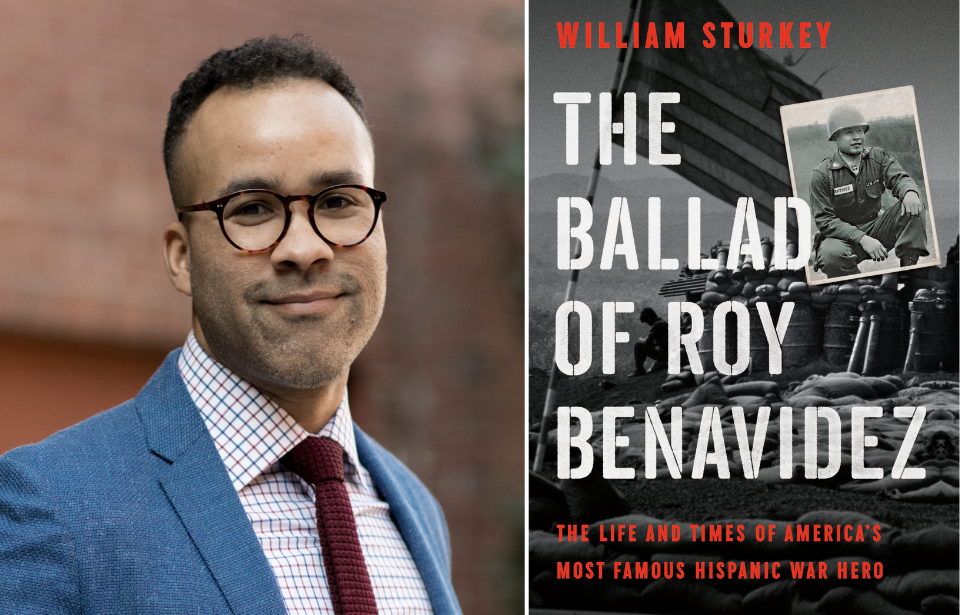

In his new book, The Ballad of Roy Benavidez: The Life and Times of America’s Most Famous Hispanic War Hero, author and historian William Sturkey examines the MACV-SOG operator’s life, from his early beginnings in Texas, to his service in the US Army and his efforts to be recognized for his bravery.

War History Online was recently lucky enough to chat with Sturkey about the book and Benavidez’s military service, along with how the anti-war climate within the United States at the time impacted those serving in Vietnam.

Before we get started, can you give us a background on yourself; how did you get interested in history and Roy Benavidez’s story?

William Sturkey: My interest in history was really rooted in my own experiences with race growing up in a rural place with a lot of racial issues. I got to college and started learning about the Civil Rights Movement, and it taught me so much about our society and race. I was just unleashed from that moment on and it really became empowering for me to learn the history of race in this country – that’s what I really gravitated to [with] history

I was pulled to this story in about 2005-06. One thing that’s important to know about me is I’m of the War on Terror generation. I graduated high school in 2000, and I come from a place where a lot of young men – especially young men and women – join the military. The military was recruiting at my high school all the time, and I have a lot of friends who served.

Being in the class of 2000, nobody knew what was going to come 15 months after our graduation. A lot of young men, working-class guys from high school, join the military to go to college. Then, of course, the war began and I was having a lot of questions about America, my role in it, what my friends were doing, and war and service.

In about 2005-06, I first heard the story about Roy Benavidez and it really resonated [with] me because I knew so many working-class kids who were fighting at that exact moment. His story about how he was recognized as a hero, but then all [of] the limitations to that just really clicked with me, based on all the things that I was experiencing and thinking about [regarding] our country and my generation.

It just never left me. I wrote a couple [of] other books, and I just always came back to this because I think those, to me, are really some of the defining questions of my generation of Americans.

How would you describe the process of writing the book?

WS: It was a bit different for me. I have a lot of experience writing about race in the South, but writing about war was a lot different and very intimidating for me because I know so many people who served, but I obviously didn’t myself.

I’m a method researcher – probably too much of a method researcher. I flew to Vietnam. I went to Cambodia. I had a private guy take me out to near where where the battle took place and all of that, but I could never recreate coming into a firefight on a helicopter or being shot at.

So I just tried to do my best with respect to those who served and those who lost their lives on all sides. I just tried to get out of the way and talk about the combat as it really happened and the simple movements with the narration.

One of the things I did find interesting was, I was not necessarily trained in Hispanic-American history – I was trained largely in African-American history – and I was just shocked at some of the differences.

Writing about Roy Benavidez, who grew up in 1930s-era, 1940s-era Texas, there was racial segregation, but it was so different than what I had written about with Black people in Mississippi. There was just so much more to it and there were all these different loopholes. It was kind of harder to parse out, really.

I had also never written about a Catholic subject before. That was so incredibly enlightening and helpful to me. To deal with the records of the Catholic Church in Texas and Mexico [was] just so great for recreating his life. A lot of poor people like him don’t have the same sort of documentary record that a lot of other people have, and that was just so helpful.

It was entering a couple of different new worlds in history for me. I really learned a lot and it was pretty challenging, but I just tried to do my best with the final product.

How did Roy Benavidez’s experience in the US Army differ from that of his White comrades? Were there any instances you found where his race impacted his service or, in general, how race played a role in Vietnam?

WS: Roy was in the military for a long time, and he was in [it] for about 13 years before his first tour. Especially during those early years, there were incidents of racism and discrimination that he faced, but he was also in the military at a time after Harry Truman had issued the Executive Order to desegregate. Hispanics had served alongside White soldiers in some units before, but then they got African Americans in there.

The military was, I think, a little bit ahead of the rest of society, largely because of [its] structure. If a captain commits against a Black cadet or whatever, then that captain could be punished through his work. Roy definitely experienced incidents of racism, micro-aggressions, things like that – just overt comments.

But when it came to Vietnam, one of the interesting things was that he was really in an isolated group of people. The MACV-SOG, they were set apart from the rest of the American troops. Roy was very unique in that he was non-White and he was one of these Special Forces guys, but there were so few of them that they really did form a brotherhood across races.

One of his best friends, who was killed on May 2, 1968, was an African-American man. He also served with White guys, and I think the guys in those units were just a little bit more insulated from some of the other racial incidents that are more famous from the Vietnam-era.

The other thing that I’ll say, too, is that Roy grew up during World War II, and Hispanic-American veterans were the big cheese in those neighborhoods. Those are the people who really experienced even worse overt racism, even after they came home. There were cases in Texas where Hispanic-American veterans couldn’t be buried with White soldiers, even though they had served their country and died for their country – like, really disgusting incidents like that – so it was actually better in Roy’s generation.

Then, during Vietnam, they had differences and they joked about it, but they were pretty close across the races in his particular unit, because I think there were so isolated and specialized.

During your research, did you find any instances of the anti-war sentiments in America impacting Roy Benavidez and/or his comrades at all?

WS: Roy talked a little bit about some of this; he didn’t really get into depth and he didn’t really talk about the context of it all, so I had to do some of my work as a historian, basically just trying to lay out what it meant to go back to fighting in Vietnam in the spring of 1968.

Roy went back in April of 1968. By that time, the tide had turned against the war in the United States. The Tet Offensive. Walter Cronkite [and] Martin Luther King, Jr. had come out against the war, Bobby Kennedy had come out against the war. Lyndon B. Johnson pulled out of the 1968 election just a couple of weeks before Roy’s deployment.

Roy just talked about how hard it was for his wife, but the fact of the matter is that, when he left from Fort Bragg, there was a huge anti-war sentiment sweeping across the country. Even the people who weren’t anti-war were starting to think, and had been convinced, like Walter Cronkite and The New York Times, that the United States could not win the war.

So he was going back to a war that some of the major figures in the media were saying, “Basically, this is a waste of time.” He was putting his life on the line for a war he feels his country didn’t really believe in anymore. So that particular timing in the spring of ’68, I think, made it all the more difficult.

Going back to Roy Benavidez’s involvement in MACV-SOG – can you explain what he and his comrades did while serving in Vietnam, for those who’ve never heard of the unit?

WS: A lot of people are familiar with the famous 1970 invasion of Cambodia – Richard Nixon said it wasn’t an invasion – but a lot of people are familiar with the famous 1970 invasion of Cambodia. The United States had troops in Cambodia for four years before that, and it started off very small. It was always pretty small, but it started out really small, and it was growing throughout the late 1960s.

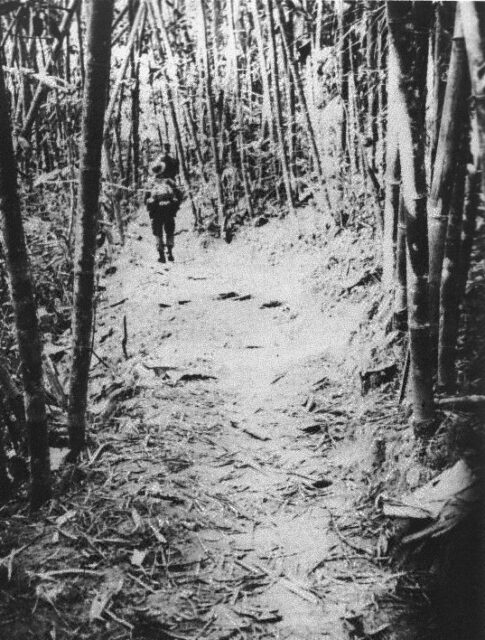

The reason that the United States sent troops into Cambodia was because so many troops and supplies were pouring down the trails, through Laos, through Cambodia, and equipping the Viet Cong in South Vietnam. It was a huge problem for the American war effort. They wanted to stop that, basically, but what they had to do was gather enough evidence to prove that their enemies were violating the treaties of the Geneva Accords and that Cambodia was not actually a neutral country.

In order to convince international governing bodies and their allies of that, they started dropping off teams – 12-man teams – of American Special Forces soldiers and these mercenaries from the highland border regions of Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam to basically study and observe (that’s what “SOG” stands for) for enemy troop movements, to then justify the future invasion of Cambodia.

When the United States did invade Cambodia, it was to stop the enemy usage of [it], but the United States had boots on the ground earlier – it just didn’t tell the American public that because it would [have] led to a huge domestic crisis, which, of course, it later did in 1970. The most famous incident from that was the Kent State shootings, these huge protests that emerged after it became public that America was in Cambodia.

But people like Roy were being sent into Cambodia for several years before the famous public invasion in 1970.

Can you provide some information about Roy Benavidez’s Medal of Honor actions while deployed?

WS: I would encourage people to read the book, of course. But what happened on that day was Roy was in this special unit, super elite, triple volunteers – that means they were volunteers for the Army; they were volunteers from the airborne and Special Forces, and a lot of these guys were older. There’s no draftees, and most of them are not young, fresh out of high school or anything like that. They’re all really smart, too.

Roy was working in this unit. He was not in the team that was sent in that day to observe enemy troop movements, but some of his good friends were. A team of 12, which was the largest number approved by the Pentagon to be dropped into Cambodia at that time. Twelve men – three Americans and nine native Indigenous guards – were dropped off very close to the Ho Chi Minh Trail about half a mile away, and they were dropped off to study and observe the enemy.

Ultimately, what happened was that they ran into the enemy twice pretty quickly. [On] the first occasion, they killed some wood cutters who were walking by, cutting a path to the jungle. One of the wood cutters got a shot off with an AK-47, and they thought that might have alerted anybody that was nearby.

They requested [an] extraction that was denied to them. Almost immediately, they ran into another group, and that’s when the firefight started.

They requested extraction. Four helicopters tried to come in. Three of them were turned away. One of them was essentially shot down and had to land a few-hundred yards away. But they couldn’t get these guys out because it turned out they were surrounded by hundreds of enemy soldiers. They had been dropped off very near to an enemy base camp.

Roy heard the gunfire on the radio that day. He was back at the base, and he jumped on one of the helicopters that came in after the first wave was pushed back. He jumped out of the helicopter, he helped establish a defensive perimeter. Long story short, he saved a bunch of lives [and] he called in airstrikes.

The helicopter that brought him in was supposed to take them out, but then [it] was shot down and [the] pilot was killed. So Roy had to re-establish the defensive perimeter [and] continue to call in airstrikes. He was medicating a lot of the men who were injured. A couple of the men he was with were shot and killed. Then, ultimately, after six hours in the field, more helicopters were called in and Roy was able to get out of there with some of those men alive.

Why do you think it took 10 years for Roy Benavidez to receive the Medal of Honor? Do you feel racial tensions in the United States were at play or was it due to government bureaucracy?

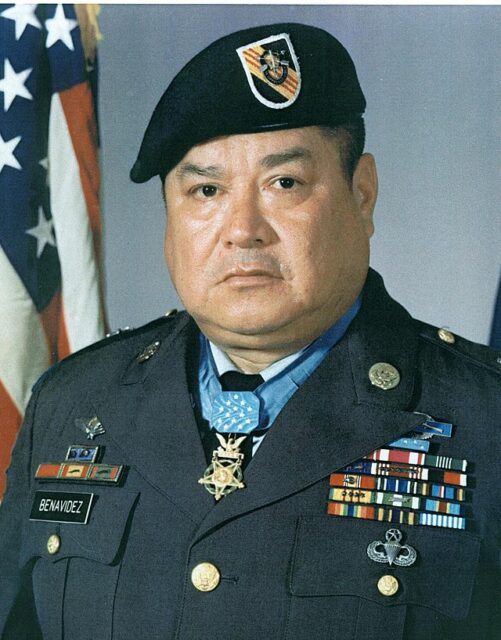

WS: When Roy started to pursue the Medal of Honor, he had suggested that race might have something to do with it. Hispanic and Black soldiers are notoriously under decorated in virtually every major conflict of the 20th century, and what the United States government has done in recent decades is go back and revisit some potential cases and award the Medal of Honor to people who they thought deserved [it] and had been overlooked.

But Roy’s unit was also notoriously under-decorated because it was so secretive. They couldn’t exactly go out advertising exactly what they were doing because it was illegal for the United States to be fighting in Cambodia like that. Also, because there were so few Americans involved, there were really only three people in the world who could have provided the eyewitness testimony required for Roy to receive the Medal of Honor, but two of those people were dead and Roy thought the third was dead, as well.

It turned out that the third man wasn’t dead. They were eventually able to find them. So part of it had to do with the nature of the combat. The United States did not want to exactly advertise that they were Cambodia in 1968 at any point in time. Even in the 1970s, they didn’t want to say that.

The Army didn’t really do him any favors, either. Roy fought and pushed to try and get the recognition he thought he deserved, and the Army just kept telling him over and over, “Sorry, we don’t have enough evidence. There’s nothing we can do.”

Ultimately, by 1980, the Army sort-of switched gears and eventually, behind closed doors and without him even knowing, helped him find the missing eyewitness who Roy had thought was dead. But it was a combination of the politics of the unit, the politics of international diplomacy.

Then, in the mid-1970s, when Roy really started pushing for it, a lot of politicians just wanted nothing to do with the Vietnam War because it was still ongoing, just the United States had pulled out and sort-of abandoned its allies, and a lot of Americans are just sick of talking about it and hearing about it.

What would you say is Roy Benavidez’s legacy?

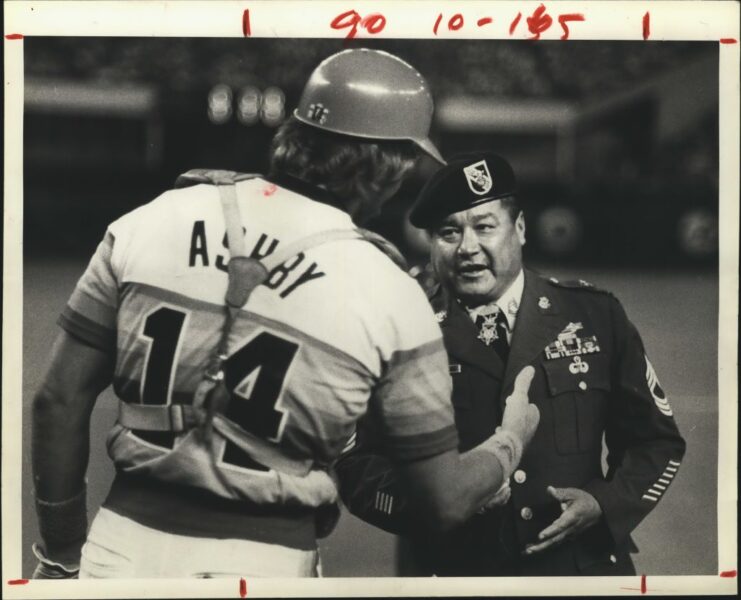

WS: Roy is unquestionably an icon and a role model for Latino soldiers in the United States military, and, of course, their percentages have only grown since the Vietnam conflict, but then also so many Hispanics all over the country.

Roy was an incredibly prolific speaker. He spoke at hundreds of venues all over the place, and he spoke at a lot of military events and a lot of patriotic events, but he spoke to probably more students than any other group.

There was there was one fall in Austin where he spoke to 7,000 students in like three days. So many of those students were impacted by seeing an Hispanic-American hero and not one [who] was a movie star or a singer, but just an everyday working-class guy who was really dedicated to his country.

They gave him letters and so much of what I understand and know about how he affected other people come [from] these letters he was sent. He would go and speak at like a fifth grade class or a high school, then the teachers might have, for the fifth grade class, “Can you send Roy Benavidez a card and tell him what he means to you.” So we have in writing what the students were saying about how he inspired them and what he meant to them.

It’s really this great range because there’s a lot of people [who] were in the service. It’s everyday people [who] were World War II veterans or even Korean veterans. They all talk to him about how much he inspired them to serve their country, to live a straight and narrow life.

Perhaps the most encouraging, I think, are from the high school students, especially at-risk high school students. He spoke in a lot of working-class schools, and he loved to speak in working-class Hispanic schools, where the students were just like he had been when he was growing up.

He would say, “Stay in school, get your degree,” all of that sort of thing and a lot of the students wrote back and said that what he said to them really mattered. To see somebody like him, who had an eighth-grade education, and to see somebody like him who had accomplished what he had in terms of becoming such a hero with only an eighth grade education. A lot of them told him that they were really inspired.

He became pen pals with all sorts of different people who he helped a lot. He wrote so many different letters and he got so much mail from people. There was a girl – he spoke at her high school – and she wrote that her mother had been killed by a drunk driver the year before and that he really inspired her to think about how to understand the risk of drugs and alcohol.

Then there were other people like a kid in Alabama, whose father had been deployed. This guy wrote to Roy, saying what a hard time he was having with his father being sent to Korea and Roy writing the kid back and telling him this is the service that your father is in, this is why it matters so much the country. We need you to be strong and support what your father’s doing.

He was doing all sorts of stuff like that, that nobody ever knew about, but it’s all in his archive. He paid his daughter to keep track of the records, so they were filed by what state they came from and when they came in. All that stuff is in his collection.

That’s one of the things that people really don’t appreciate or have any idea about Roy. There’s so many people on Facebook and stuff who talk about hearing him speak in ’97, or “I heard him speak in ’89,” but he wrote hundreds, if not thousands, of letters to people. He had all these relationships like that, where he really tried to help people with their problems.

It was one of the things that really captured me about Roy. When he was first decorated in the early 1980s, it was like, “Okay, here’s a war hero. Here’s what he did.” It was at this moment where Ronald Reagan held a huge ceremony at the Pentagon a month into his presidency. It was really the turning point for the way we remember veterans in this country.

Those are not my words. That’s what the media reported at the time. Colin Powell even talked about the Roy Benavidez ceremony in his memoir. It was a major event. But, then, later on in his life, it was like he transcended just being a war hero.

People would write to him for advice and tell him their problems. One guy asked him to speak at his wedding, do those sorts of stuff like that. They thought he carried some sort of wisdom because of what he had been through as a warrior, which didn’t always quite make sense to me. Somebody got shot seven times, why does that make them a good person to ask about your marriage? But that’s how people viewed him. That was really remarkable to me.

It’s really thinking about what place military heroes have in this country, especially in the 1980s, when the Vietnam veteran really became detached from the war itself. That’s when we got the whole resurgence of patriotic movies – Rambo, Rocky, Top Gun – all that stuff. That’s the moment when Roy was really famous.

More from us: INTERVIEW: Dr. Marshall Poe on the Mỹ Lai Massacre and Its Impact on Vietnam-Era America

So it was really interesting to me thinking about, what does it mean to be a war hero in that moment, and why do people write asking for this life advice from this man?