Malta is situated in the Mediterranean Sea, 93km south of Sicily. It is an archipeligo of many little islands – the largest of which is Malta itself, followed by Gozo and Comino. Malta was formally ceded to Britain in 1814 and became a crown colony. Although it is relatively small, having an area of only 316 sq km, and at the time had a population of approximately 250 000 persons, it became a vitally important, strategic area for the Allies during WWII.

Once the war opened up on the North African front – it became vital for Britain to have a suitable base from which to launch air and sea forces, ports for ships transporting vital supplies and reinforcements, as well as a base for launching attacks on enemy bases and shipping. Malta fulfilled all these requirements. Rommel, the commander of the North African Axis forces, was also very aware of its strategic importance and realised that control of Malta was necessary to maintain control of North Africa. This resulted in Malta becoming one of the most intensively bombed areas of WWII.

Since the conscription for military service of Maltese men from the ages of 16 years and upwards had left the workforce on the island depleted. Malta was predominantly Roman Catholic and for them, it was not seen as acceptable for women to go out to work, but the state and the church compromised, with the result that more than 10,000 women volunteered and were employed. These women – in spite of the dangers presented by the incessant bombing, the shortage of necessary supplies, the lack of proper food and the illnesses caused by that lack, together with the long and frightening hours spent in bomb shelters – persevered. These were ordinary, everyday women – the backbone of the nation, the unsung heroines – which kept Malta running while their men were at war.

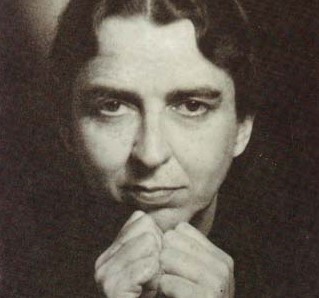

Simon Cusens, who has researched and written extensively on the role and liberation of women in Malta during the war, highlighted a few notable women who served the Maltese people during this difficult period in the country’s history. At the office of the Times of Malta, and most unusually for the time, there was a woman in charge. Mabel Strickland was bent on keeping the people of Malta properly informed and uplifted while ensuring that the newspaper would maintain their morale – vitally important to people undergoing such very difficult times. Mabel must have been a formidable lady, for to run not just one, but two newspapers (the sister publication was the Maltese Language Il Berqa ) successfully, required stamina, perseverance, good judgement and very hard work. Mabel managed to keep both newspapers going throughout the siege – and was in her offices at all hours – regardless of the time. At considerable risk to herself, she often ignored the air raid sirens, in order to get her papers out on time. Mabel was awarded the OBE for the work she undertook in order to keep these two most important information systems going – in spite of the shortages of supplies and food and in spite of the dangers of the constant bombing.

Dr. Irene Condach, one of a very few female doctors, managed – in spite of the danger and with no means of transportation– to both examine and inoculate more than 20,000 schoolchildren. During the time of the Siege of Malta she managed to hitch or walk to the various government schools and is credited with eradicating scabies from them, as well as being instrumental in starting a school medical service – and that in spite of the lack of sufficient food for the children and the heavy and constant wave of bombing raids – a real unsung heroine.

‘Mary the Man’ –a name, by which Mary Ellul was known, was a woman with truly remarkable strength. She worked as an air-raid warden which, considering the massive waves of the almost non-stop bombing which took place during the siege, was no easy task. Cusens reports that a number of people recall being rescued from under rubble by a strong, white-haired lady in uniform.

The Maltese people ended the war with the distinction of being the only entire population to be awarded the George Cross, which is Britain’s highest civilian honour for bravery. It is a fitting thank-you to all the civilians – deserved by all – but probably even more so, by its women.