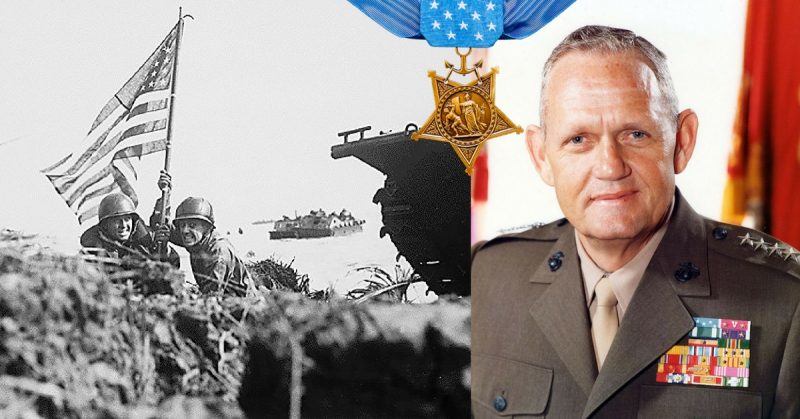

There have been a few Commandants who had been recipients of the Medal of Honor, but Louis H. Wilson was the last. And given that the entire ranks of the modern Marine Corps are currently devoid of any officers with the nation’s highest military honor it could be quite some time before the world would ever see it again. His tenure as the nation’s top Marine from 1975 to 1979 would be one of remarkable transition.

The World War II generation had all but faded out, and the Commandant who followed him would, in fact, be the last World War II veteran to serve in that position. The nation had wound down from the war in Vietnam, and the Marine Corps was subsequently struggling to reorganize and refit for a new generation.

Who better to lead them through this task than the man who received the Medal of Honor for reorganizing and refitting Marines under heavy Japanese fire on the island of Guam 30 years prior.

Just in Time for War

Lewis Wilson was born in Brandon, Mississippi in 1920 and attended college at Millsaps in Jackson, Mississippi. He graduated in 1941 and was shortly thereafter given a commission as a second lieutenant in the United States Marine Corps just in time to lead men in the war that would forever define the Corps. By 1943, Wilson would find himself serving in the Pacific with 9th Marines as they worked their way towards Japan one island at a time.

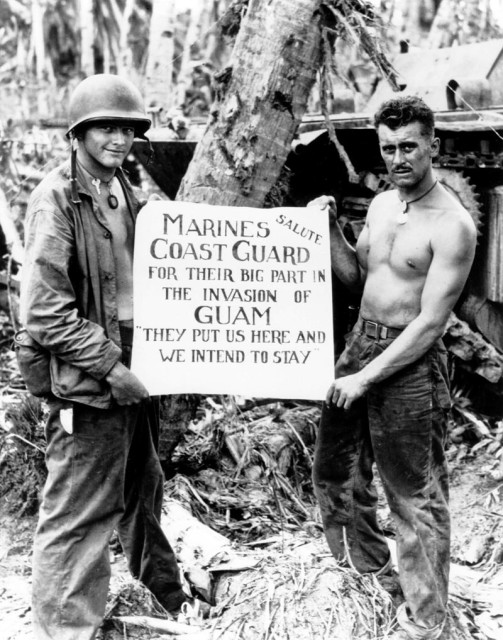

However, his hallowed place in Marine Corps history would be earned fighting for the beaches and hills of Guam. The largest of the Marianas, Guam was still only 32 miles long and 10 miles wide. The island had been in the possession of the United States since they captured it from Spain in 1898 and it was one of the earliest chunks of real estate was taken by the Japanese in December of 1941. And on July 21, 1944, it was time for the United States to take it back.

By July 25, Wilson was in command of Company F and was tasked with taking a heavily defended portion of an enemy occupied hill. The rocky terrain was wide open providing little cover for the advance forcing Wilson to lead his men over 300 yards through heavy machine gun and rifle fire.

Despite the resilient enemy, Wilson achieved his objective and began to organize for the defense.

Defending the Hill

Nearby units didn’t fare as well as the Marines struggled to organize themselves after the assault. Without hesitation, Wilson jumped in to assume command of those units and began to give directions. For the next five hours throughout heavy Japanese shelling and sniper attacks, Wilson would organize the ad hoc unit for a proper defense of their position.

They knew night would bring the Japanese counter-attack and the time to dig in was limited.

During his efforts to plan the defense under fire he was actually wounded three separate times, but refused medical attention until the task was done. It was only then that he retreated to the company command post to receive medical attention. However, as night fell the first of the anticipated Japanese assaults began and Wilson left the aid station to attend to his men.

Throughout the night in the face of heavy Japanese fire, Wilson could be seen racing from unit to unit to support the Marines in their defense. On one such occasion, he dashed out 50 yards in front of the lines to rescue a wounded Marine who was lying helpless. For the next 10 hours, they would see wave after wave of Japanese assault with the fighting often turning to hand-to-hand combat.

By morning, the last of the Japanese assaults were defeated, but this was no time to rest for Wilson. Their current position was dangerously threatened by an opposing slope prompting Wilson to organize a 17-man patrol that would once again head into the face of Japanese fire.

The mortars and machine-gun fire were so heavy, 13 of the 17-man patrol were struck down by enemy fire. And yet, Wilson and what remained succeeded in taking the strategic position from the enemy. His actions were directly credited with supporting the entire regimental mission in the annihilation of over 350 Japanese troops. For his actions that day, Louis Wilson was awarded the Medal of Honor and was about to embark on what would be a long and illustrious career in the Corps.

The Road to Commandant

Due to his wounds, Wilson was evacuated back to the United States where he would recover and continue to serve stateside throughout the rest of the war. Over the next ten years, he would attend various staff officer courses while serving in various commands building a reputation for his ability to organize and lead in peace time as well as he did under fire.

In 1965, Wilson deployed with the first Marine Division to Vietnam and served as the Assistant Chief of Staff for the Division. After returning in 1966, he put on his first star and began on the road to taking over the Marine Corps as its leader.

On July 1, 1975, he was promoted to full General and assumed his duties as Commandant of the Marine Corps. Emphasizing the need to transition during the post-Vietnam era, Wilson was a champion of developing fast-moving and highly responsive expeditionary units with a single integrated system of combined ground and air power.

These expeditionary units will become the backbone of the post-Vietnam Marine Corps and ensured a group of lethal Marines were nearby in the world wherever you should need them.

Retiring in 1979, Wilson would symbolize the ending of an era as the World War II Marines became few and far between in the active ranks. And while the Marines will always revere their commandants with respect and honor, the fact that your Commandant happens to hold the nation’s highest military honor only increases that reverence.

Wilson was undoubtedly proud of his tenure as Commandant, but it was the Marines in the hills of Guam with whom he bled that day in July 1944 who would always hold a special place with the General.