During the afternoon of the Battle of Antietam, Federal forces mounted a final assault. First they formed into a massive, mile-wide battle line on the west side of Antietam Creek. From there, the men were tasked with climbing a three-quarter mile hillside to a plateau where the town of Sharpsburg sat.

Gain that ground, and it might be possible to cut off the Rebel route back across the Potomac to the safety of Virginia. Thus far, the battle had been inconclusive, but it was still possible to destroy Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia in time for dinner.

The 9th New York would be among a handful of Union regiments that made it all the way to the outskirts of Sharpsburg. But they would pay a terrible price.

The 9th was a quirky collection of soldiers that included singers, writers, dancers, producers, set painters, and others drawn from various creative fields in New York City. The regiment’s very first injury of the war occurred when a man juggling a cup, plate, knife, fork, and spoon cut himself with the knife.

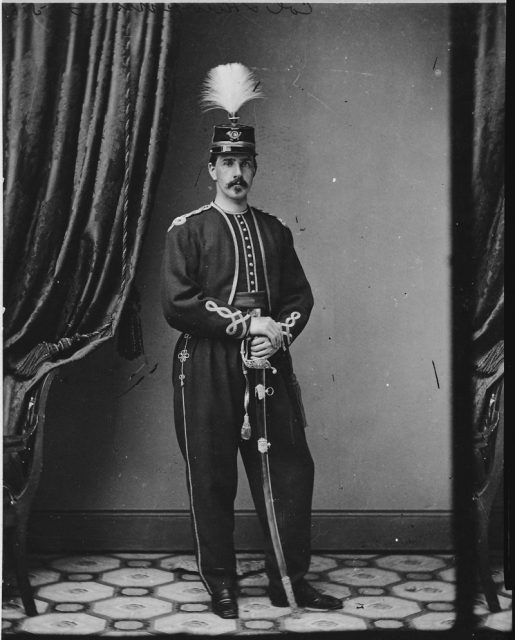

As befit their theatrical style, the soldiers of the 9th fashioned themselves as Zouaves. The Zouaves were a legendary Algerian force that outfought the French army. They wore loose fitting uniforms, ideal for hot desert warfare, and favored bright colors and enough gold braid and tassel to hobble a camel.

Sartorially speaking, the 9th New York managed to outdo even their Algerian antecedents. Without question, this was the splashiest regiment on the field this day. Its 373 members wore loose-fitting trousers, blue jackets with magenta trim, and on their heads, red fezzes with tassels. This last touch had inspired their nickname: the Red Caps.

The men had paid $21.50 each for these trappings, eschewing the standard Federal uniforms. Unfortunately, the Red Caps were among the regiments that had forded Antietam Creek to get into position for the final assault. As a consequence, their trousers didn’t billow with trademark dash; were instead sopping wet and clingy as the men stood in the midday heat.

The Red Caps began their fight with a long, nervous wait. They hunkered down behind a ridge, providing suitable protection as a seemingly endless duel played out between Union cannons, positioned on the hillside above of them, and Rebel guns stationed on the heights near Sharpsburg.

Frequently, the enemy overshot, and the shells would hurtle over them. “I noticed one of them coming like an india-rubber ball through the air,” private Charles Johnson would recall, describing a solid shot. “It struck the top of the hill, boring up a mass of earth, and then bounded high in the air, passing over our heads with a noise I can liken to nothing but the savage yell of some inhuman monster.”

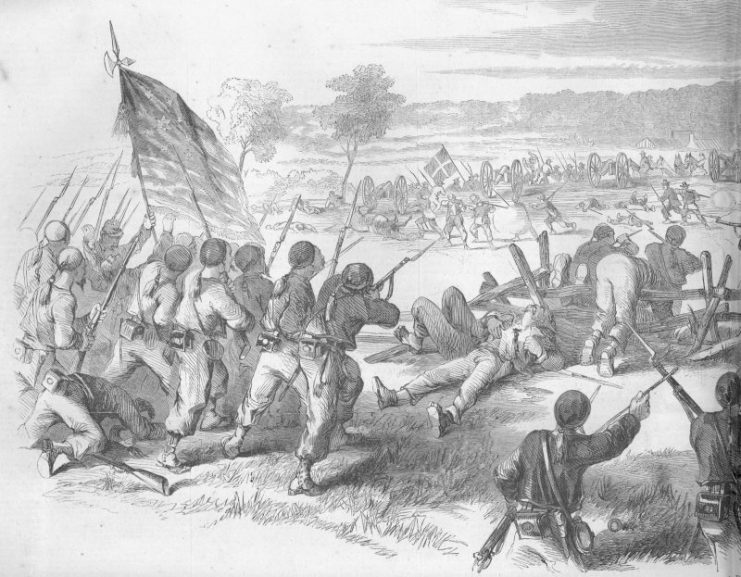

At last, the Red Caps began their advance. The portion of the ground they had to cover was rife with topographical peculiarities, a striking series of dips and rises. As the Zouaves climbed the hillside, they slipped in and out of view, fire raining down on them whenever they were in the open.

A bullet clipped a Red Cap near his ear and the man dropped his musket and launched into an oath-filled conniption. Another wasn’t so lucky as a single canister ball grooved across the top of his head, like a fatal hair parting. “[W]e lost men at almost every step,” is how Lieutenant Matthew Graham described the advance.

For the besieged Red Caps, the goal was always the next hollow. They would dash down into it, and make for the far side and the protection it offered against artillery fire. At each stop, the battle line grew shorter for loss of men. Each stop also provided an opportunity to reorganize the line. But they had to remain low.

The men of the 9th filled the gaps by crawling towards one another on their hands of knees. Then they’d climb up out of safety, and face the Rebel wrath anew. For someone standing at the bottom of the incline, the Zouave battle line would have appeared then disappeared several times, going up over ridges and down into hollows, growing progressively shorter. This would not have been an optical illusion.

The Red Caps kept going. The further up the hill they pressed, though, the more they fell into the range of enemy muskets, and they began to draw heavy fire from a pair of Confederate brigades, 600 men, including Virginians, Georgians, and South Carolinians.

Even as these Rebels unleashed a musket storm, however, the cannonade didn’t abate. All that changed was the type of ammo being used. For the Confederate artillerymen, it proved difficult to find the proper firing angle, with the 9th New York pushing ever closer, yet on a downhill trajectory.

Increasingly, the Rebels relied on canister, showering the Zouaves with iron balls. Some gunners even introduced a devious twist. They packed double loads of canister, then tilted their gun barrels toward the ground. To fire at such a severe angle caused the 54 iron balls to stay low, fanning out across the ground, then skittering down toward the Zouaves like a herd of evil marbles.

The Red Caps dove into the safety of a broad furrow. They redressed their line yet again. At least they were nearing the top of the hill.

The two Rebel brigades fell back behind the safety of a long stone wall.

Everyone waited.

On the command to charge, the Zouaves surged up and out of the furrow, howling their distinctive war cry: “Zoo! Zoo! Zoo!” Sharpsburg was in sight now; its streets could be reached in a single concerted dash. A Rebel solid shot, fired from mere yards away, slammed into the line, and the iron ball stared blackly into a soldier’s widening eyes for the briefest instant before it tore his head from his body. This proved so unnerving that the men nearly wavered. But they kept going.

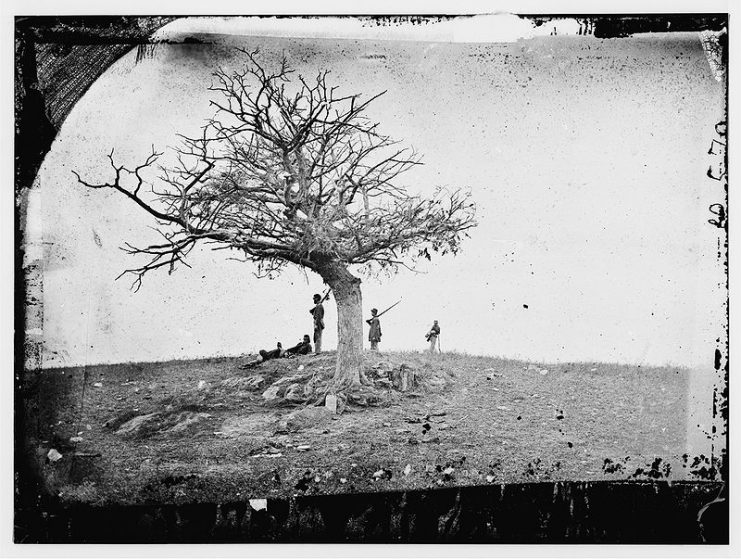

As they charged, a few of the men chanced to look back over their shoulders. All down the hill they could see their fallen comrades, strewn like red-clad rag dolls. One gravely wounded Zouave, in particular, left a haunting impression, recounted in the regimental history: “The lower portion of his jaw had been carried away, and the torn fragments that remained, together with his tongue, clotted with gore, hung down upon his breast.”

This injured soldier had raised himself up on an elbow. With his other arm, he waved his red fez, urging on his fellow Zouaves. He gave off a jaunty air, like a man casually reclining at a picnic, but one need only linger on this sight for an instant and— my god!

Under withering fire, the Federal charge began to slow. The Confederates, hunkered behind that stone wall, had staked out an intimidating position. Rebs continually popped up, squeezed off a volley, and dropped to safety only to be replaced by fresh Rebs, like some infernal carnival game. In quick succession, they succeeded in picking off the 9th New York’s color guard. Others stepped forward to secure the regimental flag, only to be cut down. Eight Zouaves were shot trying to defend their colors.

But the Red Cap line held firm and continued to inch forward. The distance between the enemies kept shrinking; only a low stone wall separated the sides.

When the Zouaves drew to within wave-to-your-neighbor range, they broke into a run and vaulted the wall. A melee ensued: angry, ugly, and chaotic. The regimental history describes it as a “scene of the wildest confusion,” even raises the specter of bayonet use, coupled with the suggestion that only cowardly Rebs would resort to such a tactic. The men traded punches and curses.

Face to sweaty, powder-streaked face, the Red Caps must have sensed the desperation of their opponents. The Rebels, for their part, would have heeded the blind rage of the Zouaves, who had lost so many during that hillside slog. With no opportunity to reload, a musket becomes a club; soldiers must have swung them wildly, crashing the heavy stocks down on skulls. Perhaps soldiers—both sides—even resorted to those gruesome bayonets.

In this battlefield bar brawl, the Red Caps emerged victors. The Rebels began streaming back towards Sharpsburg. “Oh, how I ran!” Private John Dooley of the 1st Virginia wrote in his journal. The latest 9th New York standard bearer planted the tattered regimental flag in the ground. Union colors now waved atop that plateau. Soon, other Union regiments such as the 45th Pennsylvania crested the hilltop. The Union had reached the outskirts of Sharpsburg.

In growing disorder, the Rebels retreated into the town. Soldiers became separated from their regiments. Some did so willingly, as this seemed an opportune moment to desert. Stretcher-bearers were the gawkiest runners, forced to move in tandem, weighted down by their wounded charges, but run they did as fast as they could. Horses strained, pulling cannon behind. Long-range Federal artillery had succeeded in damaging many of the Rebel guns; cannon on boggety wheels clattered down the streets of Sharpsburg.

Lee was on the scene as Sharpsburg slid into chaos. He did his part to stem the crisis, heading off stragglers, steering men back to their regiments.

All at once, Lee spotted heavy columns of soldiers in the distance marching in his direction.

He asked a lieutenant: “What troops are those?”

The lieutenant removed a telescope from a case, and offered it. “Can’t use it,” said Lee, raising his hands, still bandaged from an injury suffered right after Second Bull Run. So the lieutenant peered through the scope. “They are flying the United States flag.”

No, not those soldiers, indicated Lee. The movement that had drawn his notice was further to the south; could the lieutenant maybe shift his gaze to that spot? “What troops are those?” repeated Lee Sure enough, these soldiers were flying Confederate flags.

Lee was elated. A.P. Hill’s men had arrived. Hill—one of Lee’s most trusted generals—had set off from Harpers Ferry at dawn. He’d driven his men relentlessly, goading them on with sword slaps, making only a few brief rest stops while covering 17 miles in the rising heat.

They had recently forded the Potomac and their trousers were soaking wet. But what exquisite timing: Just when Lee’s army had been pushed to the brink of annihilation, he had roughly 2,200 fresh soldiers to throw into the fight.

Soon, the newly arrived Rebels were streaming off the Sharpsburg plateau and down the hillside.

The Union collapse now rippled left to right, as Hill’s men drove like a wedge across the middle of the slope. The most advanced Federal regiments, like the 9th New York and 45th Pennsylvania that had fought to the outskirts of Sharpsburg, were forced to yield their ground. They had scamper back downhill, lest they be sandwiched by Rebels to their front and rear.

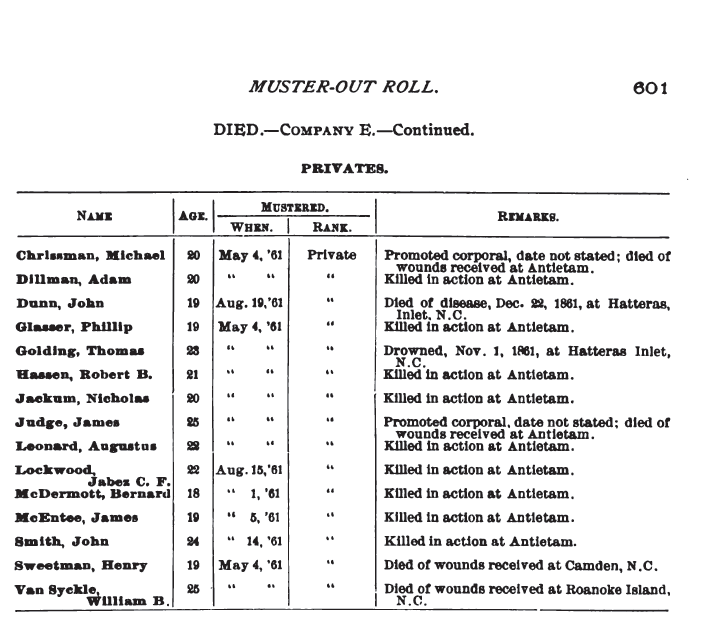

The Union had failed to cut off that vital Rebel exit across the Potomac. The battle would end at sunset, a tactical draw. And the 9th New York, which had started up that final hillside 373-strong, was devastated: 45 killed, 176 wounded, and 14 missing.

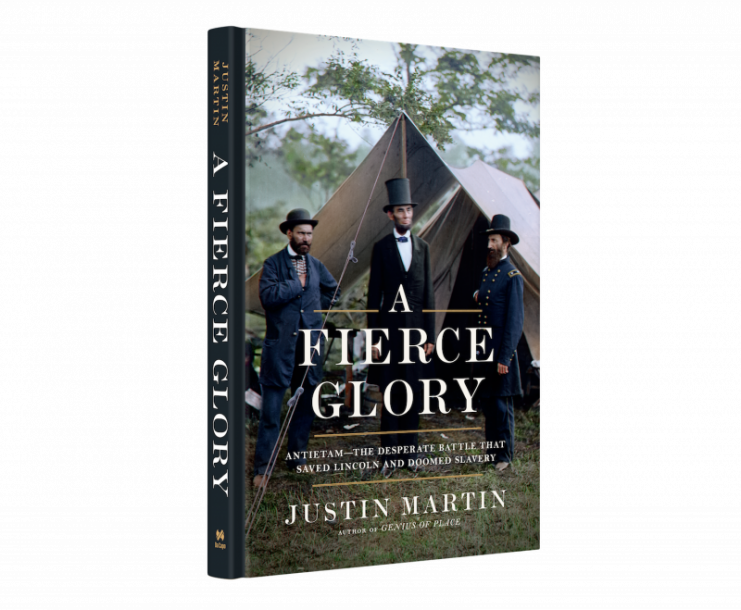

This is one in a series of posts, as guest blogger Justin Martin counts down to the September 17 anniversary of Antietam, still America’s bloodiest day. Martin’s posts will feature little-known episodes he learned about while researching his new book, A Fierce Glory: Antietam—The Desperate Battle That Saved Lincoln and Doomed Slavery (Da Capo Press).

You can order the book here and here is Justin Martin’s website.

Read another article from us – Youngest Combat Casualty in the Civil War Fell at Antietam

Justin Martin will continue to share some special and insightful stories about the Battle of Antietam throughout the week. Please stop by tomorrow to catch the next installment.