To my children and grandchildren

We’re aboard the U.S.S. Oklahoma City CLG-5. The CLG stands for Cruiser Light Guided Missile. It’s the last ship in the Navy to have teak wood decks, and it’s also the Admiral’s Flag Ship for the Commander of the U.S. Seventh Fleet. It’s November 1968 and we are on our way to Vietnam.

USS Oklahoma City CLG-5

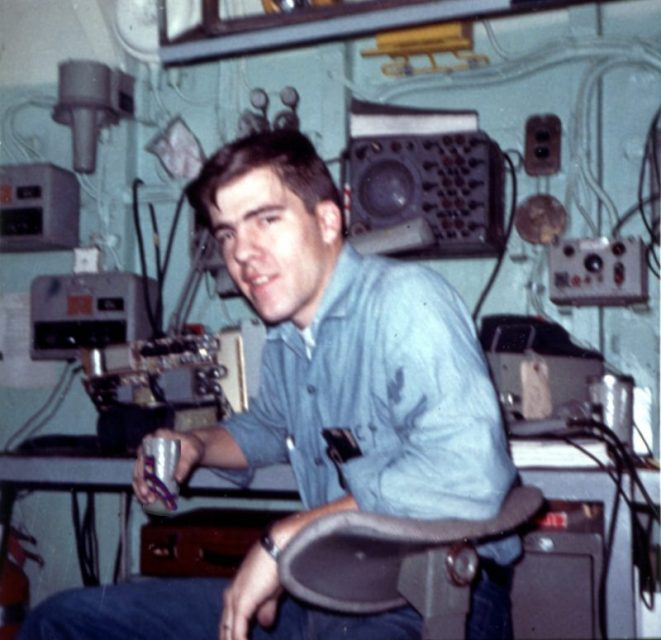

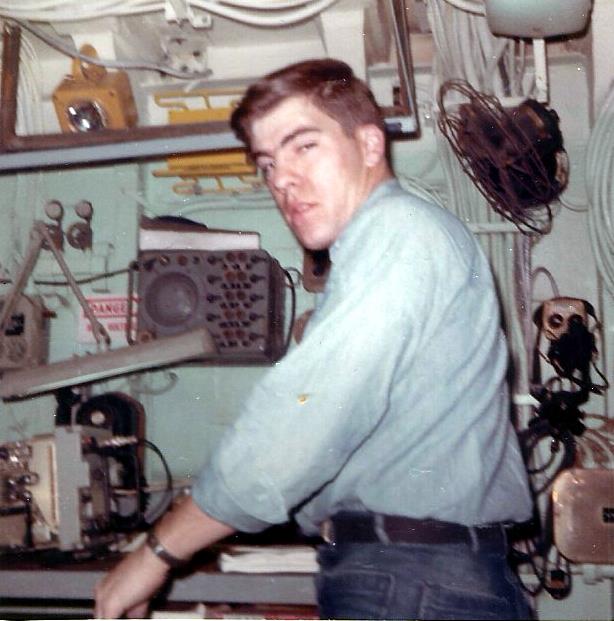

After scheduled stops at naval bases in Hawaii, the Philippines, and Japan, the anxiety levels were running high as we got underway for the Vietnam combat zone. As Second Class Electronics Technician, my duties were to maintain and repair the communications equipment used by the Ship’s Combat Information Center, located on the bridge of the ship where the Captain and the Admiral hung out.

I had decided to stay aboard ship over Christmas and not to be part of that drunken sailor stereotype for which Yokosuka, Japan, was so well known and where so many sailors had gotten into so much trouble. The problem was such that they even gave us a lecture on it before we went ashore. Little was I to know, this decision to stay on board would get me into more trouble than I could possibly have expected.

Not knowing what to anticipate in a combat situation, I was constantly thinking about how I could improve my own little corner of the world. There were two areas in particular that bothered me to no end: the amount of time it took to get the equipment out of it’s holding racks and the incredibly meticulous tuning procedures. Overall, it would take hours to get a piece of gear back on line.

While the ship was tied up in Japan for the holidays and since we weren’t in a combat situation, I decided to take on these two issues. The problem with getting the gear out of the racks to work on was that it was fastened with fine threaded bolts every inch around the outside perimeter of the equipment, about 60 bolts. As this was in the days before the advent of powered screwdrivers, it would take close to half an hour just to remove and then replace a piece of gear before it could be used and that was the shortest part of the procedure. The process of tuning up the equipment after it was removed from the rack required literally forming (bending) 40 or 50 little tabs while watching an oscilloscope for optimal changes. Between these two operations, easily 90 minutes would be expended. There had to be a better way.

So it seemed to me that removing 8 bolts would be much quicker than 60 and given the weight of the gear, 8 bolts would hold up against any wave or jolt. I simply replaced 60 bolts with 8 and used epoxy to glue the remaining cut off heads onto the equipment frame. Nobody would ever notice the difference, but it would make a big difference if time was of the essence and that would soon be the case.

The next time-consuming process was tuning up the equipment. Forming those little tabs while watching the oscilloscope was a brainless operation and took forever. However, after doing so many of them I began to notice a pattern that no one had documented. Certain tabs would have a greater effect on the output than would others, and it was always the same tabs. So what would happen if, in a pinch, I only paid attention to those tabs with little or no attention to those remaining. Bingo! It not only worked but the output was greater than it had ever been before. Unfortunately, this is where I got into big trouble.

In the process of testing the new procedure, without even being connected to the final power amplifier and antenna, I was watching the scope and modulating, talking into the microphone, thinking nobody could pick up my signal. Had we not been docked with 6 or 7 other ships I would have never been caught and had I not used the codeword for the “Admiral’s Flagship” they would never have known from where the transmission was coming. BUSTED.

The offense was such that I was summarily called before the captain the very next day. After hearing what I had done, and why, the punishment was restriction to ship for the remaining time in port. But this, as it turns out, was just the first domino to fall in an incredible series of events.

We fast forward now three weeks to January 18, 1968. We are a little south of Danang providing gunfire in support of the 26th Marine Regiment on shore. We received information that the Marines were under extreme enemy gunfire at which point we came about 180 degrees and promptly ran hard aground. General Quarters (GQ) was immediately sounded and the Admiral was flown off in the helicopter.

Ship’s propellers churning up mud

My duty station was the highest battle station aboard ship so I had about as good a view as they had on the bridge, but with the help of the ‘Big Eyes’, the huge pedestal mounted binoculars right outside my duty station, I was looking the enemy right in the eye, and I could see they were preparing to blow us out of the water. I put on my battle gear and closed the compartment’s watertight hatch. No sooner had I done that than there was a banging from outside on the hatch. It took a minute to undo all the watertight hatches. Upon opening, there stood the captain and a lieutenant with his 45 drawn – I think that is Standard Operation Procedures.

The captain refreshed my memory as to our last meeting at Captain’s Mast and that I told him of the new quick way to tune up a transmitter. He said that there were Air Force jets 100 miles out and heading in the opposite direction, but that they were on a different frequency than any of our gear. Could I tune up a transmitter from scratch before they got out of range? Domino two had just fallen, the very reason I came up with the new method.

The captain and the lieutenant were not even back to the bridge before I had a transmitter on the bench and being tuned. I don’t know what the record time was for this type of feat, but I am sure I made it. I secured the newly tuned up transmitter into its rack with 4 bolts and notified the Combat Information Center that it was ready to go. Total elapsed time, I’d guess, was 10 to 15 minutes. While I couldn’t hear what they were saying, I could tell by the output meter that it was working. What a feeling of accomplishment.

I then went back out to the Big Eyes and could see that a complete artillery battery had been set up on the beach. I heard the Air Force jets coming from behind and heard them squawk over the radio, “Looking Good Okie City,” as they flew directly over and promptly blew up the artillery on the beach. The final domino had fallen.

Later that day the ship was extracted with the assistance of USS RECLAIMER (ARS-42), the commercial tug COMMANCHE, and Yard Tug Boat YTB 779. Divers went overboard and inspected the damage which was determined to be light and we went back to providing gun support for the Marines. All in a days work.