By Jeremy P. Ämick

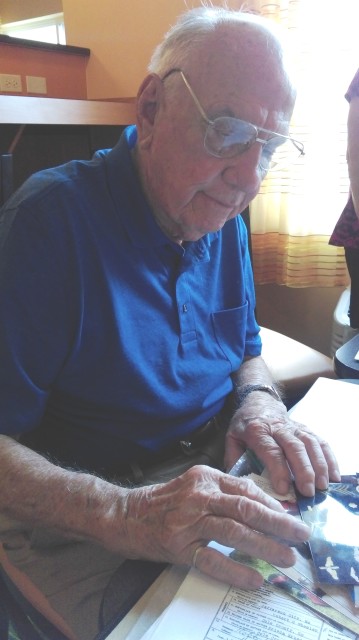

Bill Wheeler reflects on his lengthy military career with a sense of pride, recalling the many changes he witnessed during his service in World War II and into the Cold War. But, as the former Air Force pilot noted, he would not have received the opportunity to don a military uniform were it not for an older brother who laid down his life more than nine decades ago.

While living in a house on East Miller Street in Jefferson City, Mo., a 19-month old Bill Wheeler started to drown while playing in nearby Wears Creek in November 1919. It was then that his nearly 4-year-old brother, Jack, played the part of hero by rescuing his struggling sibling from the creek.

“About a month later, Jack died of scarlet fever and diphtheria,” said Bill Wheeler, 98, Savannah, Ga., while recalling the bravery of his older brother. “All because of Jack … because of what he did,” he sagely remarked, “I was able to live, to go on to have a good career in the Air Force.”

In the years following the family tragedy, his parents moved the family to St. Louis in 1931 and Wheeler went on to graduate from Normandy High School in 1935. Then, Wheeler explained, he worked for local companies and began drilling with an Organized Reserve unit before the outbreak of World War II.

“The draft came, and I think being in that reserve unit gave us a low draft lottery number,” Wheeler laughed, when discussing his induction into the U.S. Army at Jefferson Barracks in April 1941.

Initially assigned to the infantry, the recruit trained at Ft. Leonard Wood, Mo., and later traveled to Louisiana for what he described as “war games.” A short time later, Wheeler recalled, he was informed that the Army Air Corps was seeking applicants.

“I applied, passed the tests and was accepted,” said Wheeler. “First, I was sent to Brooks Field in Texas and spent a lot of time in the library studying math—algebra, calculus and the like. Everybody wanted to be a pilot, and I had heard that you had better know your math if you wanted to become a pilot.”

His regimen of self-study paid off when he advanced to primary flight training at Ballinger, Texas, and was introduced to the PT-19 Fairchild—a two seat, single engine aircraft. Several weeks later, he attended his basic flight training using a more advanced aircraft at Goodfellow Field in San Angelo, Texas.

“Then,” Wheeler continued, “I was sent over to Mission, Texas (Moore Field), to train on the AT-6, which was a much heavier, more complex airplane than those we had used up to that point. We learned to shoot targets and perform aerial acrobatics,” he added.

In December 1942, one year following the attacks on Pear Harbor, the young airman was commissioned a second lieutenant and received his pilot’s wings. Given the choice of either becoming a fighter pilot or flying “heavier airplanes,” the young aviator chose the latter.

“I was transferred to Hondo (Army Air Field), Texas,” Wheeler said. “That’s where I began to fly the AT-7, which was the first multi-engine plane that I flew and held about six passengers. We would use the plane to train navigators because that was back before we had all of the fancy electronics they have now for aerial navigation.”

Remaining at the base throughout World War II, the pilot recalls not only amassing more than 10,000 hours of flight time while training navigators but also worked with a “secretive atomic unit” and in an administrative capacity to help track operations on the large base.

“It was while I was stationed at Hondo that I was introduced to Mary,” recalled Wheeler, an unforgettable event he described as “love at first sight.” (Five weeks after first meeting, the couple married.)

As Wheeler explained, he left the service in September 1945 and returned to St. Louis, finding employment at a local shoe factory and flying with a reserve unit at Scott Field (now Scott Air Force Base), Illinois, on weekends. A year later, he reenlisted when offered a regular commission in the Air Force. (The U.S. Army Air Forces was renamed the U.S. Air Force in 1947).

He went on to fly C-119s in McCord AFB in Seattle and later became a B-47 Stratojet pilot with the Strategic Air Command, stationed at several locations throughout the United States including five years at an airbase in England.

“While I was with SAC,” he said, “the B-47 I piloted was equipped with a hydrogen bomb—it had the capability of destroying an entire city. We had orders that if something happened (during the Cold War) we were trained and prepared to drop the bomb on a specific target in the Soviet Union.”

The married father of three children retired from the Air Force at the rank of colonel on March 1st, 1970, with nearly 32 years of military service to his credit. For several decades, he has lived in Savannah, Ga., but insists his success in life remains attached to one Mid-Missouri community.

After listening to her father share his story of military service, Wheeler’s daughter, Dana Bradley, stated with evident solemnity, “For me, my dad’s story represents a full circle moment. Uncle Jack gave him life and then he went on to give life to three children and two grandchildren.”

Tearfully, Wheeler himself added, “If Jack hadn’t pulled me from that creek years ago, I wouldn’t have been here to live the wonderful life that I have.” He concluded, “I feel as though I should thank the citizens of Jefferson City as well for giving me the privilege of calling this my hometown—it always has been and always will be.”

Jeremy P. Ämick is a military historian and writes on behalf of the Silver Star Families of America.