War History Online presents this guest blog by Dave Paone

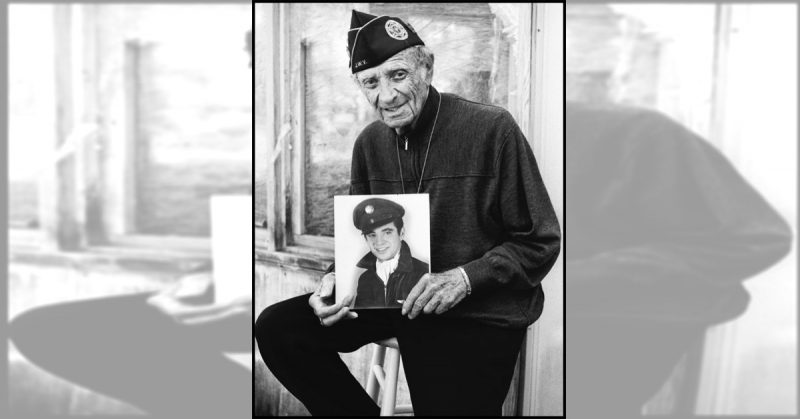

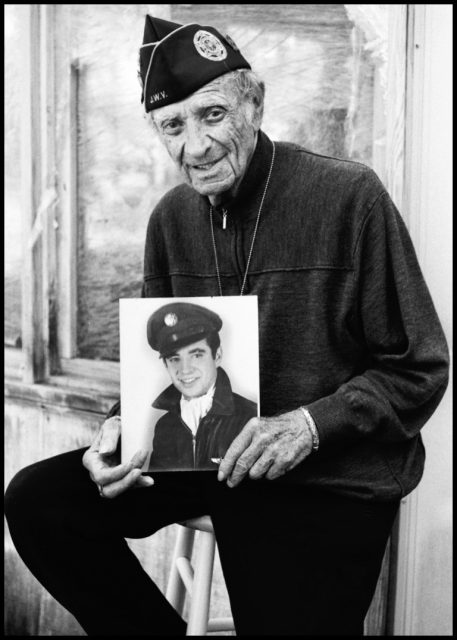

In 1945, at age 19, Stanley Feltman was a tail gunner in a B-29 for the US Army Air Corps. He had flown about 15 successful bombing missions in the South Pacific, but come mission number 16, he wasn’t so lucky.

His plane, containing 11 crewmembers, was shot down by a Zero of the Imperial Japanese Navy. All 11 men were able to escape the wreckage by inflating a dinghy and paddling away from the aircraft before it sank minutes later.

The dinghy was designed for six. That meant six were able to sit inside but five, including Feltman, had to hang onto a rope that ran the perimeter, with their bodies waist deep in the water.

And then there were sharks. They had some yellow dye (shark repellent) on hand, but it dissipated after time. At one point, another airman who was hanging on, lost his grip and slipped into the shark-infested water. Feltman dived in after him and brought him back to the surface. This act of bravery would earn Feltman the Bronze Star.

Several hours later a submarine spotted them. However, its crew was on a mission elsewhere and could not take them aboard. They wired their coordinates to an aircraft carrier which sent a PBY seaplane to pick up the stranded airmen after a total of about eight hours in the water.

A Kid from Brooklyn

Feltman was born April 5, 1926 in the Flatbush section of Brooklyn.

When the US entered the war on December 7, 1941, Feltman was only 15 and couldn’t enlist, although he wanted to. However, he could enlist at 17 with parental consent, which was his plan. Upon his 17th birthday, he told his parents of his intention to volunteer.

His mother was none too happy about this but eventually gave in.

Biloxi Blues

Even before he was shipped overseas, Feltman found himself under attack. Not from the Nazis or the Japanese, but from a fellow soldier during basic training in Biloxi, Mississippi.

There was a bully in the barracks who called Feltman names. Afraid to get into trouble, Feltman avoided him.

One day the bully stood two bunks away from Feltman’s and wouldn’t let him pass. He called out to him, “You Brooklyn Jew boy,” and told him he had to go around to get to his bunk.

“I lost my temper,” said Feltman. “And I hit him hard in the gut. He must have lost his wind. He doubled over and I swung with all my might and I hit him with an uppercut, and I caught him on the jaw. He hit the post, went down, he looked like he was dazed and I jumped on him and I started pounding on him.” Feltman was afraid of what discipline awaited him. However, the first lieutenant in charge of the section, upon hearing that the five-foot-eight, 136-pound Feltman flattened a six-foot-two, 220-pound opponent immediately assigned him to represent them in the inter-sectional boxing tournaments. Ultimately his record was 22 and 0.

Love

At his young age, with his athletic build and leading-man good looks, Feltman had no trouble finding a willing partner in the opposite sex pretty much wherever he went. His romance with an army nurse proved problematic because enlisted men were forbidden to fraternize with officers. He also shared an apartment with a civilian girl who worked at the Post Exchange while stationed in El Paso, Texas.

“Whatever base I was at, I had a woman.”

The Pacific Theater

Eventually, Fetlman found himself in the tail of a B-29 in the South Pacific. His job was to fire at oncoming, enemy planes.

Often these were flown by Kamikaze pilots, who would purposely crash their explosives-laden planes into American aircraft carriers.

Feltman recalled his first encounter with the enemy. “I remember somebody saying, ‘There’s planes coming in at six o’clock,'” he said. “I sighted on a plane that I saw coming in. I didn’t know if it was the same plane that they saw because usually they had five, six planes at one time come at you. I fired, I saw the plane blow up, so I figured it has to be a Kamikaze plane. It just exploded.”

Feltman was only 18 at the time and the youngest member of the crew. Ordinarily, the biggest worry for a male his age is finding a date for the prom. But Feltman was thousands of miles from home, in the service, and in a war zone no less. One may think this would be far too frightening for someone in his position. But no.

“I didn’t feel anything at the time. This is what I had to do and I did it. In those days you did things by instinct. You don’t think of what you’re doing; you just do it.”

After he hit his target he shouted, “I got him! I got him! I got him!”

Today when Feltman thinks about those battles he’s not so enthusiastic. He’s sure he shot down eight Japanese pilots and thinks there may be two more.

“I never felt right by taking a life,” he said. “When you’re shooting planes down, you’re taking a life. That’s all. There’s nothing big about that.”

Postwar

After the war, Feltman attended Mohawk College in Utica, New York on the GI Bill. Naturally, he found a secretary to date while he was there.

Eventually, he graduated from Utica College of Syracuse University as a psychology major in 1950.

After a broken engagement (Feltman slugged his father-in-law-to-be), he hitchhiked to San Francisco where he got a job as a cabin boy on a tramp steamer. He jumped ship in Hong Kong and soon found himself in Portuguese Macau working as a runner at a gambling house.

The powers-that-be learned of Feltman’s pilot’s license and gave him a high-paying job (making thousands of dollars) flying patrons between Hong Kong and Shanghai. After a few trips, he caught on that his passengers were highly suspect (likely Red Chinese) and he quit.

A Drastic Move

Five years prior, the Japanese were trying to kill him and he was trying to kill them. But after meeting a Japanese woman named Yoko, Feltman was smitten and wound up not only living with her in Japan, but buying a house for the both of them in Kyoto. He also learned to speak Japanese.

This whirlwind romance produced a son.

Not only had Feltman entered a domestic relationship with a Japanese woman, he befriended a former Zero pilot. The Zero pilots were the very people he was supposed to kill — and who were trying to kill him — during the war.

“Originally he was the enemy,” said Feltman. “But he became one of my best friends.”

This pilot is still alive at 92 and he and Feltman remain in regular contact, seeing each other in person when he has business in the US.

On two occasions Yoko’s family assaulted Feltman, the second time putting him in the hospital. With pressure from the US Consulate, Feltman returned to the States, leaving behind Yoko and their two-month-old baby.

Settling Down

It took 43 years, but after a second broken engagement, Feltman married his true love, Marilyn Jacobson, whom he met on a blind date, in 1968.

“As much as I was a womanizer before I met her, I never touched a woman after I met her,” he said.

Their 40-year marriage produced two sons, Richard and Scott.

Feltman worked in the tile and carpet business, at first owning his own tile company, then working for his father’s linoleum and carpet company, then working for Kaufman Carpet, then finally Dan’s Discount Carpet, the whole time in sales.

He moved to Coram, Long Island in the early 1970s, buying the first of his two houses there.

Today

Feltman is long since retired and his wife passed away in 2008. He’s had a few health problems of his own, resulting in two operations. He also has arthritis in his fingers. However, he’s still very spry for 92 and his mind is as sharp as ever.

Feltman is sometimes asked to speak at high schools about his experiences in the war and he’s a charter member of the National World War II Museum in New Orleans.

A few years ago he joined Post 366 of the Jewish War Veterans. Weather permitting, Feltman can be seen at a 7-Eleven in Coram or the Walmart in nearby East Setauket selling poppies for donations that go to the Long Island State Veterans Home in Stony Brook. He collects about $1,000 per month but his personal best was in May at over $2,000.

Sometimes when he’s out in public and sees a pretty girl walk by he says, “If I were 60 years younger….”