War History online proudly presents this Guest Piece from Jack Billington

Over one hundred years ago in April 1917 the United States entered World War I, a conflict involving all the major world powers that had already lasted 30 months, and stepped onto the world stage as a great power. Yet the long road to war was never the result of any deliberate national policy and was undertaken with a cautious reluctance that frustrated and angered pro-Allied interventionists like former President Theodore Roosevelt and Senate Republican leader Henry Cabot Lodge. In August 1914, when the guns of August erupted across Europe, Africa, and the Far East, President Woodrow Wilson urged his fellow countrymen to be neutral in thought as well as deed. It was a very hard thing to ask, and almost impossible in a world where both sides used propaganda, diplomacy, and intrigue to influence the American people and government. German- and Irish-Americans tended to favor the Central Powers, the East and West Coasts favored the Allies, and Midwesterners and Westerners overwhelmingly supported neutrality. America at the end of 1916 was a deeply divided country.

As in 1861, 1941, and 2001, it would take an extreme provocation by a hostile power to unite the country and provide the political backing for a formal declaration of war by the U.S. Congress, as required in the Constitution. The provocation might have remained buried in history or not revealed until after the war if not for a minor naval incident in the Baltic Sea during the first weeks of the war in 1914. That incident, so little noted at the time, would change modern history and ensure that the United States would lead the Western world in the last half of the 20th century and the first decades of the 21st century.

From 1 August 1914, the day that Germany and Russia went to war, the Baltic Sea was dominated by the Imperial German Navy, the second largest in the world, but the Tsar’s far smaller fleet made occasional forays from Petrograd (present-day St. Petersburg) and her Finnish and Baltic ports, just to show the Kaiser’s beloved navy that the Russian bear had sharp teeth, even at sea. Among the islands and treacherous shoals of the Gulf of Finland, it was largely a war of smaller ships, destroyer flotillas, fast light cruisers, and submarines, all seeking exposed and vulnerable victims that might be removed from the other side’s naval list without too much risk or damage to their own forces.

One of the first such casualties of this war at sea in the Gulf of Finland was the German light cruiser Magdeburg, which ran aground on an island off the Estonian coast and fell victim to Russian light cruisers happy to find a stationary target. The German captain ordered his crew to abandon ship and sent his radioman to drop the naval codebooks in deep water where they could never be recovered. Before this German sailor could do his duty, he was killed. The codebooks were discovered in a life raft along with the dead radioman by enterprising Russian sailors engaged in fishing Germans out of the freezing Baltic and promptly turned over to their superiors.

Russian naval intelligence was overwhelmed by the treasure trove that had fallen into their laps, the communication codes of Imperial German Navy and, more important, the key to unraveling their ciphering system, since all German codes were enciphered to make them absolutely unbreakable. The Russians, whose expertise was in spying on their own citizens, knew they did not have mathematicians and technicians in their ranks to use this priceless intelligence properly, information that might decide the outcome of the war. They might spend 10 years working on the cipher before they succeeded in breaking it, and Imperial Russia did not have 10 years. Their British allies, however, did have that capability.

So, the Imperial Russian government made one of its last intelligent decisions before humiliating defeats, enormous manpower losses, and collapsing morale led to abdication and revolution. In October the Russian embassy in London passed on the codebooks to the director of British Naval Intelligence. The next month, one of the most remarkable men of World War I, Rear Admiral Sir William Reginald Hall, became Director of Royal Navy Intelligence, a position he would hold until his retirement in 1919. Known as “Blinker” Hall, the new director established a secret code-breaking and radio communication intercept unit in Room 40 of the Admiralty Building.

Over time, even as it expanded with more personnel and greater space, the code-breaking unit became known as Room 40. Other encryption and codebooks fell into British hands as a result of covert operations in Persia, where German provocateurs were suborning an anti-British insurgency, and through an Austrian radio operator in Brussels who had spent most of his life in England. Lives were sacrificed to acquire these codes and ciphers, including that Anglophile Austrian in Brussels, and not all were silenced by Germans. By the spring of 1916, Room 40 was reading the full text of German naval and diplomatic wireless radio and cable traffic being sent around the world.

Blinker Hall took great care to ensure that the German government and military remained blissfully unaware that the British were listening in on and understanding their confidential communications. There was little need to worry, as it turned out. It was inconceivable to the German cryptographers and their masters that their highly complex codes enciphered by a multiplicative pattern of random numbers could ever be broken by befuddled Englishmen who had spent their professional lives attending yachting regattas and firing the occasional naval shell at rabid Chinese Boxers and Bible-thumping Boer riflemen. No one in German counterintelligence ever became suspicious. It was, like the Enigma cipher machine a generation later, the best-kept secret of the war.

As 1916, one of the worst years in the history of Western civilization, came to a close, the Germans were approaching desperation. On the Western Front alone they had lost 800,000 killed, wounded, and missing during the 10-month Battle of Verdun and five-month Battle of the Somme. The British and French had lost 1.2 million men in these battles, but that was little consolation to the German nation, which was running out of young men to feed into the meat grinder. Boys of 16 and middle-aged men of 45 were being conscripted. The Germans knew that time was not on their side. The British naval blockade was slowly but surely strangling the life out of Germany. Her people were starving, reduced to a diet of turnips. Strategic materials were in short supply.

Imperial Germany’s High Seas Fleet under Admiral Reinhard Scheer, the surface navy that had been the Kaiser’s prewar symbol of national prestige, had made a bold foray into the North Sea on 31 May 1916 in a forlorn attempt to break the British blockade but failed to achieve decisive results in the Battle of Jutland off the Danish coast, barely making it back to port during the night and early morning. British losses in warships and men were much higher and Scheer could claim a tactical victory of sorts, but the strategic result was defeat with the German surface navy confined to home ports, where it would remain until its surrender in 1918. The Royal Navy easily afforded the losses at Jutland and still retained decisive superiority in numbers of battleships and battlecruisers. They were the jailers, and the Germans were the inmates with no place to go.

Germany’s allies were becoming restive and starting to have doubts about the ultimate victory of the Central Powers. The Austro-Hungarian Emperor, Franz Josef, who had ruled since 1848, died in November, and his heir, the Emperor Karl I, was already looking for a way out of the war that would leave the Habsburgs with something left of their empire. Ethnic minorities were clamoring for self-rule and seeking recognition from the Allies, deserting the ranks of an Austrian army that was fighting on three fronts. Only the presence of German divisions stiffened their resistance and kept Austria from collapse. How long they could continue to do so was problematic.

In the Middle East, the Turks were on the defensive with an Anglo-Indian army of a quarter of a million men under Sir Stanley Maude pushing up the Tigris River toward Baghdad. The Arabs in the Hejaz of the Arabian Peninsula were in full revolt against the Turks, armed and supported by the British in Egypt and on the Sinai peninsula. Among their British advisers was an eccentric and brilliant young officer and former archaeologist, Captain Thomas Edward Lawrence, who would be made internationally famous by the war correspondent Lowell Thomas as “Lawrence of Arabia.” The Ottoman Empire and caliphate — corrupt, venal, and oppressive — was dying, kept in the war by the presence of German commanders, German weapons, and increasingly more German troops grudgingly transferred from other war fronts.

The least of Germany’s allies, Bulgaria, was under constant pressure from a growing Anglo-French-Serbian army bottled up in the Greek port of Salonika, the last Allied stronghold in the Balkans. The war that Bulgaria’s King Ferdinand had joined in September 1915 to recover territory lost to Serbia and Greece in the 1913 Second Balkan War was proving to be longer, much more expensive in lives and treasure, and far riskier than Foxy Ferdinand, as this master of intrigue was known, had ever imagined it would be.

Germany was officially still led by a civilian government under Chancellor Theobold von Bethmann-Holweg and the elected deputies in the German Reichstag, a constitutional monarchy that had been established by Bismarck, but the civilians made few, if any, decisions related to the conduct of the war. Even the Kaiser, who in 1914 exercised far greater political authority than his first cousin, Britain’s King George V, was now not much more than a figurehead who agreed to any policy that his army and navy general staffs put in front of him to sign. Germany had become a military state under the virtual dictatorship of its two most prominent soldiers.

On 29 August 1916 Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg, the victor over the Russians at Tannenberg in 1914 and Warsaw in 1915, replaced Erich von Falkenhayn, the architect of Verdun, as chief of the Imperial General Staff with his brilliant and relentlessly ruthless chief of operations, General Erich Ludendorff, as first quartermaster general, a title that meant nothing but held more power than any single person in German history until the advent of Adolf Hitler. Hindenburg was the indomitable face of German authority, and Ludendorff was the power behind the scenes. Hindenburg and Ludendorff were the real rulers of the German Empire. They dictated the strategy, economies, and foreign policies of all the Central Powers and tolerated no opposition. They were, in effect, the most powerful men in Europe.

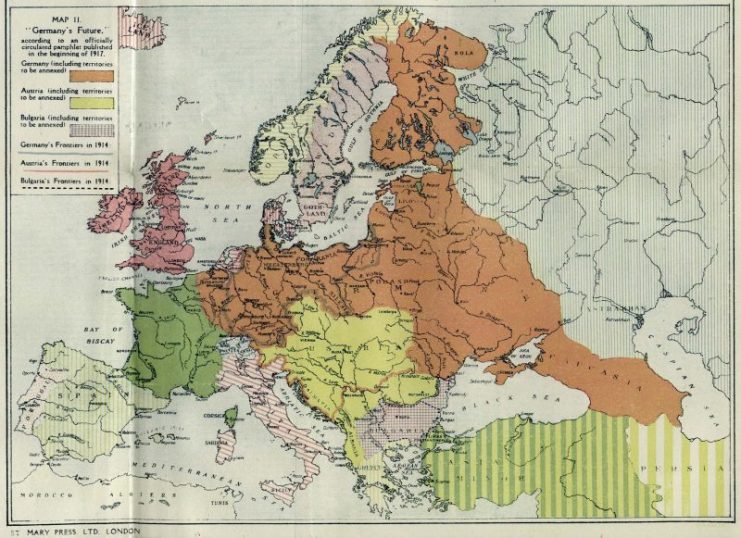

While Hindenburg and Ludendorff planned to win the war in 1917 and annex to the German Empire vast conquered territories, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson was trying to keep America neutral and offer his services as a mediator to negotiate a compromise peace between Germany and the Allies. Indeed, he had won reelection in November 1916 on the slogan “He kept us out of war.” An idealist and progressive to the core of his being, Wilson proposed a peace without victory for either side in which the frontiers of 1914 would be restored, none of the belligerents would pay any indemnity, freedom of the seas would be guaranteed, and colonial claims decided on a basis fair to both sides. It was a way out of a war that no one seemed able to win, and Wilson was hopeful until the end that reason would prevail over emotion and greed. Of course, it did not.

Ludendorff thought that Wilson was a weakling and a hypocrite. The German army on all war fronts was well established deep inside the territory of its enemies, and those gains had been won at a high cost. The first quartermaster general and the general staffs of the army and navy regarded any peace without annexations as favorable to the Allies, showing Wilson to be pro-Ally and anti-German. The British and French governments, who had conquered Germany’s four African colonies, could not face the voters at home in the next election and tell them that more than a million French and half a million Britons had died for nothing. Wilson’s pleas for peace without victory fell on deaf ears in Germany, which offered peace terms that amounted to a demand for Allied capitulation. The Allies were more tactful, politely but firmly rejecting Wilson’s offer in London, Paris, Rome, and Petrograd.

On 9 January 1917, a day on which the world was changed forever, the military and civilian leaders of Imperial Germany met with the Kaiser at the Castle of Pless near the Polish frontier. Ludendorff and the chief of the German Naval General Staff, Admiral Henning von Holtzendorf, had persuaded Hindenburg that the time was right, and dictated by necessity, for Germany to initiate a policy of unrestricted submarine warfare against all ships, neutral along with belligerent, in the war zone the Germans had declared around the British Isles. Unrestricted meant that ships would be torpedoed without warning and no effort would be made to rescue survivors. Everyone understood that this policy would in all likelihood bring the United States into the war on the Allied side.

Germany’s civilian government — facing civil unrest, strikes, and socialist Reichstag deputies demanding peace — needed to support the decision, if only to spread the responsibility if things went wrong. Hindenburg, Ludendorff, and Holtzendorf assured the Kaiser and Chancellor Bethmann-Holweg that no U.S. soldier would ever set foot in Europe — long before the Yankees could ever raise, train, equip, and transport an army, the U-boats would already have won the war. German economic experts had calculated in scientific fashion with carefully compiled statistics that Britain would have to surrender in four months to avoid starvation and complete economic collapse.

Chancellor Bethmann-Holweg was doubtful. He warned Ludendorff and Hindenburg that war with the United States would bring catastrophe to Germany, that the American colossus possessed unlimited financial and industrial resources, and that U.S. belligerency would raise the morale and hopes of all the people in every Allied nation. Ludendorff dismissed these points. The United States, he argued, had no army to speak of: only 200,000 regulars, no tanks, no heavy artillery, and only a handful of flimsy aircraft flown by just 50 military aviators. The American President actually boasted of being “too proud to fight.” The Americans would have no effect on the outcome of the war that the U-boats would win in a matter of months. Bethmann-Holweg bowed to the pressure and reluctantly signed on to the strategy of unrestricted submarine warfare.

Jack Billington is a former officer. As an officer, he studied military history, and after service, history is still interesting for him. He devotes his free time to conducting shooting courses with firearms. Also, he writes a BLOG about home & self-defense training tips.