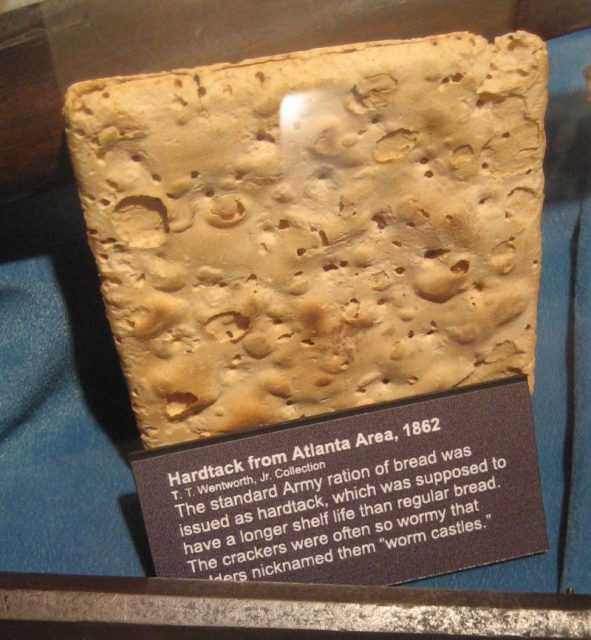

Hard Tack

Although recorded uses of “Bisket” or “hard tack” (literally meaning hard food) date to the Roman Legions and Richard I’s Crusades, it officially became part of the military staple for the Royal Navy in the 1660s.

The hardtack was a mixture of wheat flour, water, and salt. By baking the biscuit multiple times, all moisture was drawn out of it.

The biscuit was so resilient after the baking process that it kept indefinitely. In fact, during the U.S. Civil War, some 13-15-year-old hardtack stored from the 1846–48 Mexican-American War was issued to the military.

It is not surprising then that hardtack was not a favorite for the men who had to eat it. Several sources have suggested the ways in which military personnel would try and alter the aptly named “tooth breakers.”

One such way of altering hard tack was to soak it in water, beer, coffee, or rum. This would not only draw out the infestation of weevil maggots hidden in the tack, but it would also work to soften the biscuit, making it easier on the teeth.

Another method was to create “Skillygalee,” defined as: “A thin broth prepared by soaking hardtack in water and frying with pork fat.”

Compared to the peak of modern rations eaten in today’s forces, hardtack ranks low on the list of things humans should consider eating.

A gallon a day

In the 1600s, the Royal Navy was not often able to store fresh water aboard its ships. What water there was kept on board was often fouled on long journeys. Consequently, sailors were supplied with a gallon of beer a day.

Although not as strong as modern beers, being only between one and three percent alcohol, a gallon of beer would certainly help wash down the hard biscuit. Marcus Rediker writes in his book Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea:

“Drinking occupied a central place in seafaring culture, so central in fact that Barnaby Slush was moved to say that ‘liquor is the very cement that keeps the mariner’s body and soul together.'”

Although it is hard to imagine modern soldiers fighting a battle or flying a fast jet after drinking a gallon of beer, alcohol was an intrinsic part of a sailor’s daily life. Woodes Rogers once remarked that “good liquor to sailors is preferable to clothing.”

While heading out on long voyages, even when fresh water was available, it seemed the objective of the Navy at this time was to provide a gallon of fluid either mixed with wine, rum, or brandy, depending on the climate.

In addition to the small nutrition and feeling of being full the gallon no doubt provided, some scholars have suggested that the alcohol ration was good for morale and the camaraderie of the crew. A contemporary example of this comes from John Balthorpe, a sailor in 1670:

“So that when saylors gets good wine They think themselves in heaven for the time: It hunger, cold, all maladies expels, With cares of the world we trouble not ourselves.”

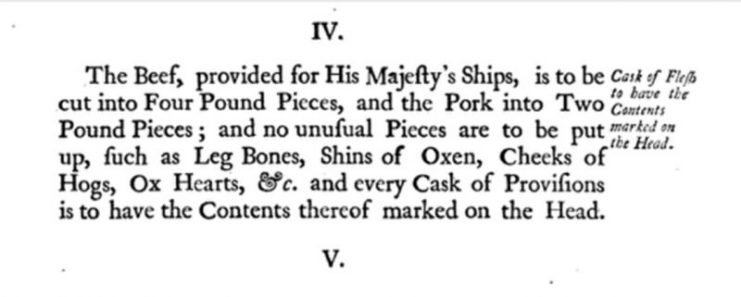

Salted Meat

Another ration for the 17th century Royal Navy was salted meat: pork, beef, and fish were a staple of former military life. While it is reasonable to assume a cut of meat would be preferable to the hardtack mush, this was not always the case.

Ever corrupt, the victuallers of the armed forces would attempt to give low-grade cuts of meat mixed in with the normal cuts. An attempt to counter this was laid out in Regulations and Instructions Relating to His Majesty’s Service at Sea. Printed in 1731, it reads as follows:

“The Beef, provided for His Majesty’s Ships, is to be cut into Four Pound Pieces; and the Pork into Two Pound Pieces; and no unusual pieces are to be put up, such as leg bones, shins of Oxen, cheeks of hogs, Ox Hearts etc.”

Assuming the Navy’s command to the victuallers was heeded (and it can be assumed that in some cases it wasn’t), the salted meat required an enormous preparation process.

It was rubbed with salt and then brined multiple times in order to remove all blood and moisture from the cut. This rendered it, by some accounts, almost inedible.

In his book, Mother, may you never see the sights I have seen, Warren Wilkinson described a scene of the 57th Massachusetts Veteran Volunteers in which, during the last year of the U.S. Civil War, the salted beef was so putrid, dry, and foul-smelling that it was piled on a stretcher and given a mock funeral while bandsmen played a “eulogy dirge.”

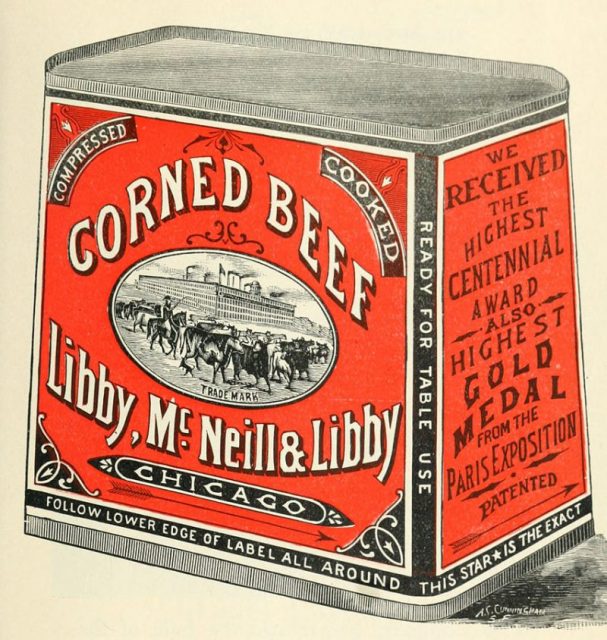

Bully Beef

While the invention of canning might seem relatively simple, it was a revolutionary innovation and a welcome gift to the soldier class.

Essentially, canning made the delivery of fresh foods easy. As a result, soldiers had access to healthy, nutritious meat that kept indefinitely and wasn’t as foul as the salt beef of the past.

Staggeringly, the bully beef ration wasn’t removed from the British Armed Forces until 2009. From the Second Boer War, through World War Two, the war in Iraq, and finally Afghanistan, the canned meat survived.

Often boiled into a hash with potatoes or served with later variants of the dreaded hardtack, bully beef was, though not perfect, a major improvement compared to putrid salted meats.

However, the officer class throughout the history of many armed forces have always eaten well in comparison to the average foot soldier.

The ordinary soldier was left for the most part underfed and disappointed. Harry Patch, the last British veteran of WW1, offered his account of rations during the war:

‘Our rations – you were lucky if you got some bully beef and a biscuit. You couldn’t get your teeth into it. Sometimes if they shelled the supply lines you didn’t get anything for days on end.’

Maconochie stew

While the invention of canning was a revolution in food preservation, what came inside the can needed work.

Aside from bully beef, another option for a WWI frontline soldier was Maconochie stew, described as follows by Matthew Richardson in his book, The Hunger War:

‘Open a can of Maconochie and you find a gooey gob of grease, like rancid lard. Investigate and you find chunks of carrot and other unidentifiable material, and now and then a bit of mysterious meat. The first man who ate an oyster had courage, but the last man who ate Maconochie’s unheated had more. Tommy regards it as a very inferior grade of garbage. The label notwithstanding, he’s right.’

Military rations, although bettered by invention, were still nowhere near equal to the modern provisions described later in this article. Described by John Brophy as a “man killer,” the stew made the monotony of bully beef preferable.

‘Vinogel’ and WWII improvements

By WWII, military rations were a far cry from their predecessors. Greater variety and quality meant that soldiers got the nutrition they required and, in some cases, a much-needed morale boost.

When supply lines held, British soldiers could expect bully beef, biscuits, chocolate, boiled sweets, oatmeal, soup, chewing gum, tea, powdered milk, sugar, matches, and toilet paper in their rations.

In the time of Napoleon, French soldiers had relied partly on rations and partly on what they could plunder from the land. By the time of the First Indochina War, however, rations had improved drastically.

At the Battle of Dien Bien Phu in 1954, one of the interesting items on the menu for French soldiers was “Vinogel,” a dehydrated block of wine that could be rehydrated with water to provide the French forces with a home comfort.

Nicknamed “Tiger Blood” by troops, it was often eaten as a solid block, no doubt to maximize the concentration of alcohol.

After canning, the greatest advancement in the logistical nightmare of feeding vast forces was air supply.

Air drops significantly effected the soldiers’ diets as perishables could be delivered to the front lines quickly and without the risks of ground transport. At Dien Bien Phu, several luxuries were dropped to the troops including beer, champagne, and ice.

MRE’s and the modern day

France is lauded for having some of the best (if not the best) cuisine in the world. The modern French Army’s standard rations are no exception to that rule.

Some of the meal items included in the standard 3,200 calorie day pack are Venison terrine, Sauté of rabbit, Stewed Beef Bourguignon, Chicken rice with ratatouille, and many other options.

Compared to hardtack, the modern day “Meal ready to eat” or MRE is a decided improvement.

Also included in some modern ration packs is a water-activated exothermic chemical heater or a small solid fuel hexamine stove. Combined with a mess tin, these stoves allow soldiers a hot, nutritious meal in almost all cases.

Religious or cultural dietary requirements can also be met by the modern MRE: Kosher, Halal, and vegetarian options are available to today’s soldier.

Seasoning and spices allow for personal preference. A selection of hot drinks and snacks gives variety and should, compared to bully beef, boost morale.

Read another story from us:

It is fair to say that the rations of armed forces around the world have improved drastically. From the days of putrid salted pork and larvae-infested biscuits to Venison terrine and Champagne on ice, it seems apt to conclude with the words of American comedian, Jackie Gayle:

“I idolized my mother… I didn’t realize she was a lousy cook until I went into the army.”