War History online proudly presents this Guest Piece from Jeremy P. Ämick, who is a military historian and writes on behalf of the Silver Star Families of America.

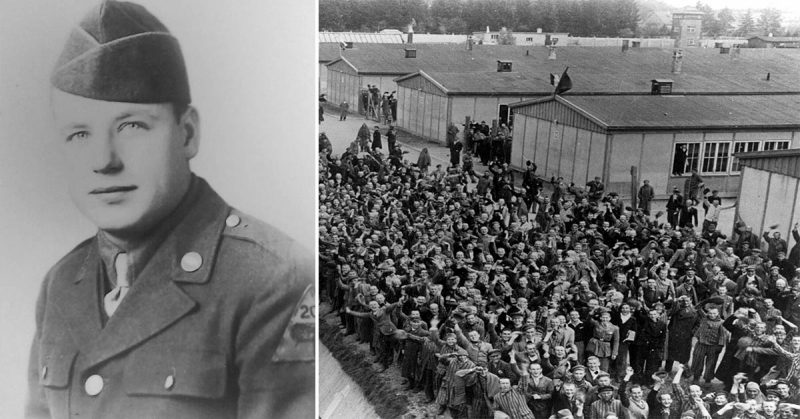

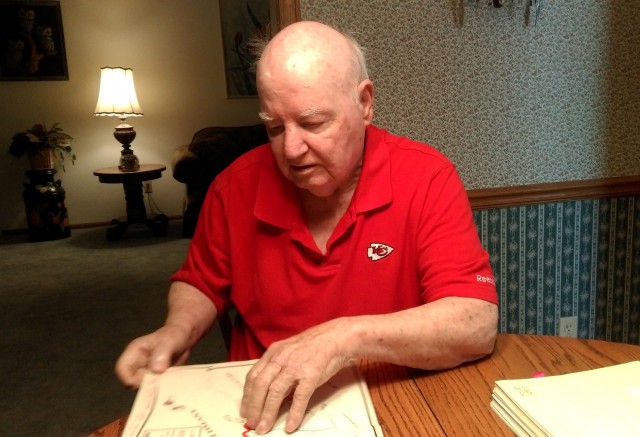

Much of Van Williamson’s life has been that of travel, as past employment has moved him to and from several locations throughout the U.S. But as the California, Mo., resident related, the pace of such movement is something to which he grew accustomed while storming across Europe with the 20th Armored Division in World War II.

Born and raised in the Kansas City (Mo.) area, Williamson began repairing motor boats at a local marina while still in high school; however, after graduating in 1942, he received a piece of paper notorious for its potential consequences.

“I turned 18 and got my draft notice two weeks later,” said the 91-year-old veteran. “That’s how they did me … they didn’t even give me a chance to enlist,” he chuckled, when describing the beginnings of a three-year military journey.

In March 1943, Williamson donned an Army uniform and traveled to Camp Campbell (now Fort Campbell), Ky., to complete his basic training. He went on to attend a gunnery school at Ft. Knox, Ky., learning the mechanics and operation of lighter weapons, such as pistols and rifles, in addition to the heavier artillery and anti-tank guns.

Later in his training cycle, Williamson explained, the Army recognized the potential value of his previous marina experience and sent him to a military boat repair and maintenance course in Milwaukee, Wis.

“The Army obviously recognized what I had done in working with boats in Kansas City and knew that I was the person to do that for the Army, too,” he said.

According to Williamson, he received notice that his division would travel to Europe to relieve the men who had been fighting it the Battle of the Bulge since the middle of December 1944.

Boarding a troopship in early February 1945, Williamson arrived in Le Havre, France days later, missing the “Bulge” by only a couple of weeks; however, the young soldier did not realize he was only weeks away from participating in another lethal engagement.

“When we got to Laon, France, they began to break us up into whatever we’d be doing—whether you were going to be a tank driver, a mechanic, halftrack operator …,” he said.

Attached to the 220th Armored Engineer Battalion under the 20th Armored Division, Williamson began the move across France and into Belgium as U.S. forces fought toward Germany. Though he recalls several skirmishes along the way, Williamson affirmed that one of the most ingrained of his wartime experiences was the crossing of the Rhine River in April 1945.

“I was on a boat helping push the bridge pieces together so that tanks and other equipment could cross into Germany,” he said. “We got the bridge up—mostly—before the fighting started … but when it did, that was a fight!”

Though his service in a combat environment was punctuated with stressful moments, Williamson noted that there were instances of unanticipated respite from the action, specifically, when they liberated the German army of some precious provisions.

“Sometime after the Rhine, we captured a German train that was carrying beer,” the former soldier grinned. “We took all that we wanted of the beer and drank it while traveling to the next place,” adding, “but I didn’t care much for that stuff … it was a lot different than what I was used to.”

As the division pressed on, they crossed the Danube River on April 28, 1945, and, the following day, became one of three U.S. Army divisions to liberate Dachau concentration camp. According to an article on the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum website, as American forces approached the camp, they discovered 30 railroad cars filled with corpses of former captives.

“There were a lot of guys that looked half-dead,” Williamson somberly recalled, “… and of course, there were many more that never made it.”

With their liberation duties behind them, the division continued to Salzburg, Germany, and remained in Europe until late July 1945, returning via troopship to Camp Kilmer, N.J.

Following a brief period of leave, Williamson continued in his service with the Army, believing he would soon deploy to the Pacific; but when Japan surrendered in September 1945, he married his fiancée, Betty, since he knew his time in uniform was close to an end.

He received his discharge on February 12, 1946 and in later years went to work for the Caterpillar Corporation, which carried him to several locations throughout the United Sates. In 1979, he moved to Mid-Missouri, and now lives in the small community of California.

When asked why memories from his participation in a war now seven decades past appear undiminished by the passage of time, Williamson responded with the insight of a man who has witnessed more than his share of unpleasant situations.

“A lot of people have tried not to remember their service because they want to forget about it,” he paused, “people died … and they don’t want to remember that, but many of us World War II veterans are still here and we have a story to share.”

He added: “We did what we were sent to do, to put it simply, and it was an important moment in my life.”