War History Online presents this Guest Article from Martin K.A. Morgan

The U.S. history memory of the Battle of New Orleans has traditionally focused on the January 8, 1815 action on the plain of Chalmette. Although certainly a climactic engagement, it is but one action among many, and there is much more to the story. For nearly two centuries, this narrative has drawn attention away from the broader subject of Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane’s campaign in the Gulf of Mexico – a campaign that ranged across 300 miles of littoral from Apalachicola Bay to Barataria Bay, and included combat operations stretching from August 1814 to the end of hostilities in February 1815.

But looking beyond the battle of January 8th to the end of the following month provides a more nuanced understanding of the military actions that unfolded in the broader New Orleans area – one that challenges a prevailing discourse that has remained popular for more than a century.

For most people, the Battle of New Orleans is remembered as a climactic victory for U.S. forces; one in which they decisively swept the enemy from the field of battle. But is this an accurate version of the events that unfolded near the city in late 1814 and early 1815? Did U.S. forces thoroughly defeat the British and send them into a hasty, disorderly retreat at Chalmette on January 8th? Or did something somewhat less dramatic and conclusive occur?

The reality is that, following the battle of January 8th, the British successfully executed a complicated exfiltration operation that withdrew their fighting force intact from the plain of Chalmette, through the cypress swamps and bayous to the east, and on to Lake Borgne and ultimately the transports waiting in Mississippi Sound. That same force then carried out successful amphibious landings on Dauphin Island and at Mobile Point in (what is now) Alabama, followed by a siege operation that resulted in the capitulation of the U.S. garrison of Fort Bowyer on February 12, 1815.

The British force was then poised to attack New Orleans a second time by following the overland route from Mobile that would have brought it across (what is now) the Mississippi Gulf Coast, and through St. Tammany Parish to Lake Pontchartrain and the lightly defended northern approaches to the city. But time ran out and the war came to an end before the British could commence this renewed overland drive toward New Orleans. So why have these events been overshadowed by January 8th? Blame it on a song.

In 1959, a pop song written by Jimmy Driftwood and recorded by Johnny Horton swept the United States and began to climb the charts. Titled The Battle of New Orleans, it presents a hyperbolized account of the battle that unfolded on the plane of Chalmette on January 8, 1815, and does so in a boastful and bombastic way that does not accurately document the event. In fact, Horton’s The Battle of New Orleans makes it sound as if General Andrew Jackson’s forces pushed the British off of the field of battle in a wild route that drove them swiftly away from the area around the city. The song’s lyrics describe a story of an enemy thoroughly trounced, thrown into disorderly retreat, and pushed back into the sea:

They ran through the briars and they ran through the brambles

And they ran through the bushes where a rabbit couldn’t go.

They ran so fast that the hounds couldn’t catch ’em

Down the Mississippi to the Gulf of Mexico.

Though this popular song is not to be confused with a scholarly account of the Battle of New Orleans, it is nevertheless noteworthy as the prominent landmark in the creation of a popularized narrative for this moment in U.S. history. Billboard’s number 1 ranked song for the year 1959, it has reached more people and attracted more attention than any book or article, and it influenced an entire generation’s understanding of the battle. The immense popularity of this Grammy award-winning composition has cast a long shadow over the subject and has contributed meaningfully to the emergence of a popularized narrative of the battle.

It is an historical perspective that can be easily assimilated into the overall triumphalist narrative of American history: one that imagines a progression through a series of transformative experiences leading toward a uniquely enlightened and redemptive destiny. Within this narrative, American fighting spirit and combat skill are imagined as being infallible, and the enemy is depicted as plagued by struggles and setbacks as if a divine force is working against them. Here, victory over the British at New Orleans is more the result of predestination than effective planning or inspired leadership. Although Johnny Horton’s song may have at one time served an important role as a teaching aid, it nevertheless distorts the reality of what actually happened at Chalmette.

Following the January 8, 1815 battle, the British force did not immediately retreat from the area. Despite what Jimmy Driftwood and Johnny Horton would have us believe, they did not “run” through briars, brambles, or bushes. In fact, they remained in their camp at the De La Ronde Plantation and, more importantly, they remained dangerous. In spite of the heavy casualties sustained during the fight in front of Line Jackson on the 8th, the enemy force still numbered over 5,000 men capable of fighting another battle, and they remained under the competent officer leadership of Major General Sir John Lambert.

During the week that followed January 8th, Lambert’s force treated wounded (from both sides), guarded prisoners of war, and interacted with their American opponents for the purpose of exchanging those prisoners. Lambert eventually began the difficult task of withdrawing his force from the area in an exfiltration operation that would follow the route that had been used in December to infiltrate through the swamps and bayous between Lake Borgne and the plain of Chalmette. This critically important time period – the one that followed the battle of January 8th and concluded with the final withdrawal of British troops – has never been a secret, nor has it been lost to posterity for want of historical record. It was well documented by several eyewitnesses, perhaps most notably Major Arsène LaCarrière Latour, General Jackson’s chief military engineer.

In his book Historical Memoir of the War in West Florida and Louisiana (1816) Latour left a chronicle of the day-to-day experience of being in close proximity with an opposing force that had not been completely defeated. Starting on the afternoon of the big battle, Latour’s account describes the situation at Chalmette:

January 8, 1815 – In the course of the afternoon, the enemy sent a flag of truce, proposing a suspension of arms, for the purpose of burying the dead. General Jackson would grant a suspension for no longer than two hours, and only for the left bank (Latour, p. 176).

Although reciprocal flags of truce passed for several hours, at 4:00pm American artillery resumed fire and bombarded the British line. Major Latour described how, on January 9, 1815, General Lambert acknowledged General Sir Edward Packenham’s death in an exchange of letters with General Jackson over the subject of the recovery of British dead from the battlefield. On January 10th and 11th, Latour noted that nothing occurred “worthy of remark” as the two armies stared across the plain of Chalmette at one another to the accompaniment of occasional artillery fire.

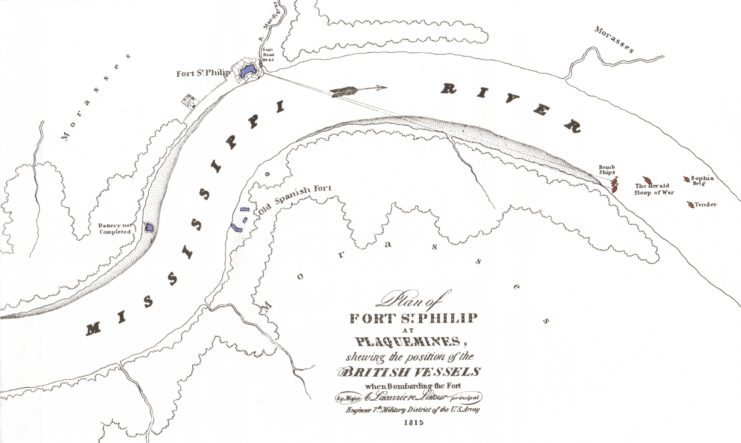

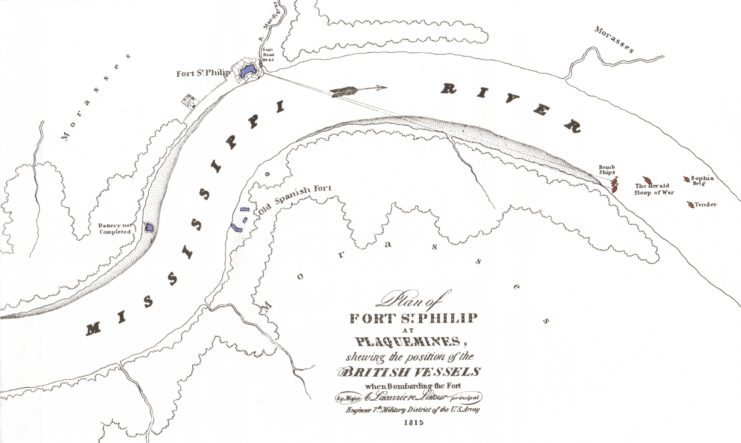

But the unremarkable situation at Chalmette during the days immediately after the big battle contrasted noticeably with the drama that commenced 55 miles to the southeast during that same time. Shortly after midnight on January 9th, a task force of five Royal Navy vessels (a sloop-of-war, a brig-of-war, a schooner, and two bomb boats) sailed up the Mississippi River to Plaquemines Bend near present day Triumph, Louisiana.

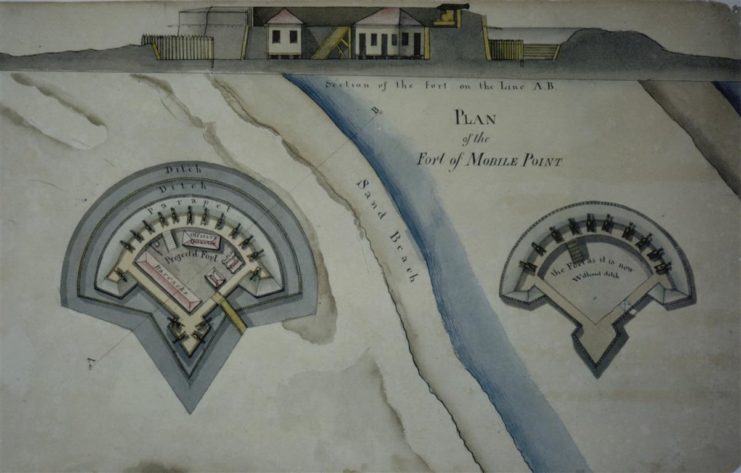

From a range of three and a half miles, the vessels opened fire on Fort St. Philip, an irregularly shaped defensive fortification built by the Spanish between 1792 and 1795, and occupied by U.S. forces in 1808. By introducing this new threat at a different point of the compass, the British sought to create a diversion that would distract attention from what Lambert was doing closer to New Orleans. Major Latour’s entry for January 15, 1815 noted when the situation there began to change:

Several officers on our lines, who had long followed the military profession, perceived on the 15th some movements in the enemy’s camp, which they thought indicated a retreat (Latour, p. 179).

A deserter who came across the lines that same day informed the Americans that the observed retreat would indeed take place soon. So, it wasn’t until a full week had passed after the battle of January 8th that Jackson’s force detected any signs that the British were preparing to withdraw. The mortar bombs falling on Fort St. Philip though, told another story entirely – one suggesting that the contest for the city of New Orleans was not quite over yet.

On January 17, 1815, a meeting took place that arranged for the exchange of prisoners of war:

On the 17th of January, in consequence of proposals made by General Lambert to General Jackson, the latter appointed his aid-de-camp, Colonel Edward Livingston, to confer with Major Smith, military secretary to General Lambert, between the lines of the outposts, for the purpose of drawing up a cartel of prisoners (Latour, p. 179).

The opposing sides concluded the prisoner exchange on January 18, 1815:

The next day towards noon, conformably to the articles of the cartel, the enemy delivered to us, on the line, sixty-three of our prisoners; the greater part of whom had been taken in the affair of the 23rd of December (Latour, p. 180).

Earlier that morning, the 366-man garrison at Fort St. Philip had observed the British gunboats descending the river and leaving. Although more than a thousand shells had been fired at it between January 9th and the 18th, the fort had held. The following day, Lambert made good his withdrawal from the plane of Chalmette:

On the morning of the 19th, a doctor belonging to the British army arrived at our lines, with a letter from General Lambert, informing General Jackson that the army under his command had evacuated its position on the Mississippi, and had, for the present relinquished every undertaking against New Orleans and its vicinity (Latour, p. 184).

Before abandoning the Chalmette area, Lambert had been careful to protect his exfiltration route by having a “strong redoubt enclosing huts” built on both banks of Bayou Mazant (now known as Bayou Villere) where it met the Villere Canal. Withdrawing troops simply followed a “corduroy road” made of perpendicularly oriented logs running alongside the canal until they reached this redoubt, and then continued eastward using a path on the south bank of Bayou Mazant.

A “breastwork” on the east bank of Bayou Jumonville (now known as Bayou Ducros) protected the spot where it was necessary for the troops to cross that body of water using a bridge of boats, and a “piquet guard” whose responsibility it was to hold any pursuing Americans at bay, manned the outpost. Continuing along Bayou Mazant for another half mile, retreating forces then had to cross Bayou Catalan (now known as Bayou Bienvenue), where yet another breastwork had been built to protect the withdrawal operation. They then had to march a distance of about a mile using another stretch of “corduroy road” that crossed the “prairie” at a pronounced crescent bend in the bayou.

Now only a half-mile from the western shore of Lake Borgne, retreating forces entered the protection of a “strong work” that could contain as many as 1,000 men. Its purpose was to protect the delicate operation of transferring men onto the boats and barges that would carry them down the final stretch of Bayou Catalan, and across Lake Borgne 50 miles to Cat Island on Mississippi Sound. They did not exactly run through the briars and the brambles, did they?

After being informed of the British retreat by a note from General Lambert on the morning of January 19th, the Americans briefly pursued them along this rather complicated exfiltration route, and a skirmish followed:

Colonel LaRonde, accompanied by colonel Kemper, and a detachment of Major Hinds’s cavalry, went in pursuit of the enemy through the prairie. They took four prisoners beyond the redoubt erected at the forks of Bayou Mazant and Villeré’s canal, and advanced within a mile of the forks of Bayou Bienvenue, where, concluding from the confused sound of voices they heard, that the enemy must be very numerous, and that it would be imprudent to advance any farther, they returned and made their report to General Jackson (Latour, p. 186).

When the cavalry detachment under Major Hinds reached the redoubt at Bayou Mazant/Villere on January 19th, it was unmanned and abandoned. Pushing beyond that point they encountered and exchanged fire with a covering force, which is the point when the four prisoners mentioned in Major Latour’s account were captured. Pressing on from there, the cavalrymen then found the 1,000-man redoubt on Bayou Catalan/Bienvenue to be occupied by a “very numerous” British force, and so they broke contact and withdrew. The next day (Friday, January 20, 1815), the British were gone. They had withdrawn from the plane of Chalmette intact after only a minor skirmish with American cavalry. For the insignificant cost of four prisoners, Major General Lambert had presided over a delicate and complicated maneuver that can only be described as wildly successful. After inheriting a disaster on January 8th when command devolved to him, Lambert thoughtfully and skillfully brought order to chaos, thus laying the framework for THE final battle of the War of 1812.

Even as Lambert’s force retired from the battle area, General Jackson greeted the development with suspicion. Major Latour recorded that, “On the 20th of January the General made the necessary dispositions for the protection of the most vulnerable parts of the country, in case the enemy should attempt a new attack” (Latour, p. 197). The following day (January 21, 1815), the cold and exhausted troops positioned along Line Jackson were finally allowed to return to the city of New Orleans. Not even this relaxation of posture was total though, because General Jackson took the precaution of leaving the U.S. Army’s 7th Infantry Regiment at the Rodriguez Canal to guard it, just in case.

So, despite what Jimmy Driftwood and Johnny Horton would have you believe, two full weeks after the battle of January 8th, General Jackson was still redeploying forces out of an abundance of caution for what the enemy might do. Although the British sustained heavy casualties during their failed attempt to seize the city of New Orleans on January 8th, their presence continued to represent such a meaningful threat that genuine concern about another attack somewhere in the area weighed on the general’s mind. Clearly, Lambert’s men did not run “so fast that the hounds couldn’t catch ’em,” – rather, they remained in the area for two more weeks and they remained dangerous.

By January 22nd, their retreat to Cat Island was complete and the immediate threat to New Orleans had dissipated to such a low that a Service of Public Thanksgiving was held the following day at the St. Louis Cathedral. But while the Americans attended their Mass on January 23rd, the British were preparing for their next move. For Lambert, the war was not over and New Orleans could yet be conquered, so he began the multi-day task of re-embarking his force on Admiral Cochrane’s fleet. The revised plan to capture New Orleans would involve first moving the fleet to Mobile Bay in what is now Alabama, and then landing the infantry near the city of Mobile. From there, the force would move west over land 100 miles to St. Tammany Parish, Louisiana. Once there, the British could either approach New Orleans from the north by crossing Lake Pontchartrain, or advance on the city of Baton Rouge to the west.

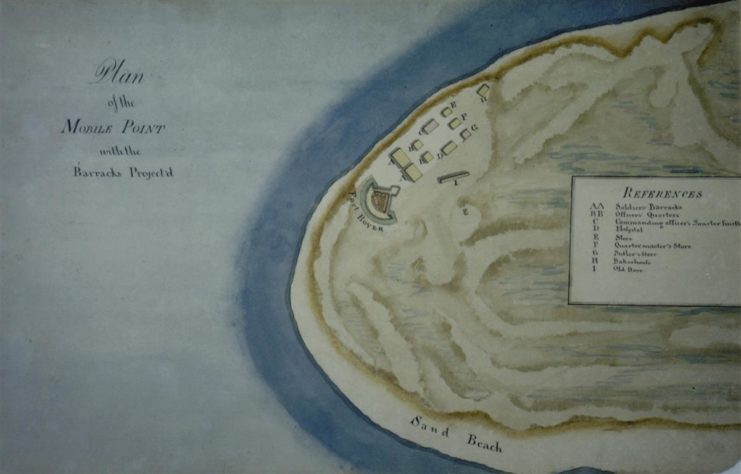

To them, the failure of the battle of January 8th at Chalmette represented a setback, not a final defeat. They remained powerful, dangerous, and determined to reach the objective, so the revised plan moved forward. By January 27th the re-embarkation was complete, but Admiral Cochrane’s vessels were compelled to ride at anchor for an entire week as a result of bad weather. But when the sky cleared on February 3rd, Cochrane began moving east along Mississippi Sound. Before the overland expedition could begin though, they would first have to contend with Fort Bowyer, an earthen stockade mounting twenty-two guns that had been built at the mouth of Mobile Bay in 1813 by the U.S. Army. In September 1814, the fort’s garrison succeeded in holding off an attack by a light force that had come over from Pensacola, but Cochrane and Lambert were about to give it another try – this time with a heavy force.

On February 6th, the troops inside Fort Bowyer observed British ships near Dauphin Island on the west side of the mouth of the bay. The next day, the fleet disembarked an element of Lambert’s troops on that island and then moved into position on the east side of the bay near the fort. On February 8th, a force of 5,000 men landed three miles east of Mobile Point at a place that is known to this day as Navy Cove, cutting Fort Bowyer off from reinforcement by land. Soon thereafter the British began digging siege works (trenches and parallels) on the north side of the fort and then, on February 10th, even more troops came ashore at Navy Cove.

Despite sporadic exchanges of musket fire during the day, the British commenced another trench on the south shore of the point at a range of only 300 yards. The Americans awoke on February 11th to find that the enemy had advanced his trenches to within 40 yards of the fort’s outer ditch, and that an impressive array of British firepower was already in position and ready to open fire: eight howitzers, two mortars, four 18-pounder guns, and a few other pieces of “inferior caliber” (Latour, p. 212). This development was particularly troubling because Fort Bowyer was built to be an anti-ship battery and its armament was therefore oriented toward the water so that it could direct fire on vessels attempting to navigate into the bay using the natural channel. The British had thus circumvented the fort’s umbrella of fire entirely by landing on the bay side of the peninsula at Navy Cove (Latour, pp. 207-213).

The 375 men inside Fort Bowyer were outnumbered, outgunned, and cut-off. To make matters worse, Fort Bowyer had no bombproof structures that could be used as shelters during an artillery bombardment, and the fort’s ammunition was exposed and therefore just as dangerous to the defenders as it could be to attackers. In contrast with the swamps and marshes surrounding Fort St. Philip below New Orleans, the ground of Mobile Point was firm and greatly facilitated Lambert’s siege operation. Lieutenant Colonel William T. Lawrence, commanding the fort’s garrison from the Army’s 2nd Infantry Regiment, could see no other course of action. For five days his men had held their ground against an ever-tightening noose of British naval and ground forces.

To hold out any longer might mean a significant loss of life, and so at 10:00am on February 11th a white flag was raised above the fort, and a suspension of hostilities was quickly established. Major General Lambert and Lieutenant Colonel Lawrence concluded the surrender in an official ceremony the following day – February 12, 1815 (Latour, pp. 207-213).

Cochrane and Lambert were preparing for an assault on the city of Mobile when, two days later, the sloop of war HMS Brazen arrived from Barbados bearing news of the Treaty of Ghent (Latour, p. 216). Although it had been signed on December 24, 1814, the War of 1812 would not be considered officially over until the treaty received the U.S. government’s full ratification. That came two days later, on Thursday, February 16, 1815, when the Senate approved it unanimously in a 35 to 0 vote. President James Madison signed the treaty later that day, and peace finally became official only after Secretary of State James Monroe presented the fully ratified document to Anthony St. John Baker, the British chargé d’affaires who had been sent to Washington to conclude the matter.

With that, the War of 1812 came to an end. Forty-one days had passed since the January 8th Battle of New Orleans and just five days had passed since the actual last battle of the war at Fort Bowyer. News that the Treaty of Ghent had been signed led Cochrane and Lambert to cancel the planned attack on the city of Mobile, and the concomitant overland expedition that would have brought the War of 1812 back to southern Louisiana.