War History Online presents this Guest Article from Tyler Turpin

How long do you think the U.S. Army has been involved in closing bases or restructuring them for new purposes? Most people think only about the context of the post-World War I and II activities and the end of Cold War restructuring of the U.S. Armed Forces. Yet base realignment and closure (BRAC) has been a practice of the U.S. Army for centuries. One of the first documented leases of a multi-building Federal Government site to the private sector was an arsenal in Virginia in 1837. More than one site has seen multiple post-Army uses. Uses have ranged from Behavioral Healthcare, educational, and manufacturing, We can see this principle at work as we look back through the history of our federal arsenals. 2015 was the 200th anniversary of the bill that created the Army Ordnance Corps and authorized the construction of additional federal arsenals. It was also the 150th anniversary of the end of the Civil War.

During the Revolutionary War and through the first few years of the country’s existence, the U.S. Army depended almost exclusively on foreign manufacturers for arms. Desiring to break this reliance on foreign supply, Congress authorized President George Washington in 1794 to establish a federal manufacturing arsenal at Springfield, MA.

A bill was signed by President Madison on May 14, 1812, formally creating an Ordnance Department in the U.S Army. The Commissary-General of Ordnance was charged with inspection, storage and issue of firearms, as well as supervision of the government “laboratories” or workshops, where gun carriages, muskets and other arms were made. Elaboration of the duties of the Ordnance Department followed in 1815. The Chief of Ordnance, after the 1815 bill was signed by President James Madison, was responsible for the contracting for arms and ammunition, the supervision of the government armories and storage depots, and the recruitment and training of “artificers.” The 1815 bill was the result of a review of issues faced by the army in the War of 1812. Some of the lessons learned during this review included:

- Transportation and routes of supply must indispensably be provided for in war planning

- Arbitrary allocation of resources to ensure a flow of supplies to sustain the war effort

- When critical shortages exist in national resources, some assured means of supply must be secured, whether it be by stockpiling or other means

- Mobilization of manpower and resources for war must be planned in advance to avoid inefficiency, waste, and defeats.

This bill permitted the Army to build additional arsenals and storage depots where its leaders saw the need.

Before the construction program began, resulting from the authority granted by the 1815 bill, there were six federal arsenals.

- Springfield, Massachusetts

- Harpers Ferry, Virginia (later West Virginia)

- Watervliet near Troy, New York

- Rome, New York

- Allegheny in Lawrenceville, PA

- Watertown, Massachusetts

These arsenals, under the command of Ordnance Department officers (or for some periods prior to the Civil War, by civilian superintendents), were typically manned by a small cadre of military personnel and a large number of skilled civilian “artificers’’ to maintain and store weapons and at some facilities to manufacture them.

Over time, however, many of these arsenals outlived their usefulness. It was not efficient to maintain those facilities. Therefore, a provision written into the Army Appropriations Act for 1854 gave the Secretary of War the explicit statutory authority to abolish any arsenal that he deemed unnecessary or useless. As a result, thirteen sites that had been constructed by the U.S. Army for weapons production or storage and maintenance were subsequently sold to private sector firms or transferred to state and local government agencies for reuse. The Army began in 1873 this closure of arsenals because the systems of roads, railroads, telegraph, and (by the mid-1890s) telephone systems rendered them unnecessary. In the following paragraphs, we’ll examine what occurred with these thirteen sites. Some of the facilities had been damaged in the war or were found unnecessary in the post-Civil War reorganization of the Armed Forces. Watervliet is the only facility built prior to 1815 that is still operated by the Department of Defense. It is the production center for large caliber cannon and mortars for the DoD.

1. The Kennebec Arsenal

The Kennebec Arsenal was built between 1828-1838 on the east bank of the Kennebec River near Augusta, Maine. The building of the complex was directly related to the Northeast Boundary Controversy, a border dispute which lasted from 1820-1842 and almost led to a third war with Great Britain. Colonel George Bomford of the Ordnance Department requested in a report, “The arsenal would also have facilities for the manufacture of ammunition to have the capacity to act independently if Maine were cut off from southern New England.” The Kennebec Arsenal was closed by the Army in 1901. Four years later the property was transferred to the State of Maine for the expansion of the adjacent Maine Insane Asylum which opened in 1840 and was later renamed Augusta Mental Health Institute. Most buildings were retained and converted for use by the hospital or other state and federal agencies. Some were demolished. The hospital closed in 2004 but the former arsenal buildings had been vacated before then. The former arsenal portion of the complex was transferred to a private developer in 2007 with conditions that reuse activity occur and the buildings be maintained. Eight structures, built of locally obtained granite (one of brick), still stand.

2. The Lake Champlain Arsenal

The Lake Champlain Arsenal in Vergennes, Vermont was built between 1816 and the 1830s. It closed in 1872. The site and structures were transferred to the State of Vermont in 1873. A correctional facility for juvenile offenders, the Vermont Reform School (after 1900 known as the Vermont Industrial School, and after 1937 as the Weeks School, in honor of former Governor John E. Weeks) moved to the arsenal site and structures in 1874 and closed in 1979. After the correctional facility closed, the site and structures were leased by the State to the Federal Department of Labor’s Job Corps program as the Northland Job Corps Center. The arsenal is built in the Federal style, with stone. It has a hip roof and its dimensions are 80 feet x 36 feet with 28-inch thick walls. On the interior, the arsenal originally had two large, open floors and a basement level paved with stone block. Six stone pillars support the first floor. According to the 1885 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, the second level was used at that time as a roller skating rink for students at the school. In the early 20th century, the interior was remodeled for use as a school building, and these alterations remain intact today.

The Officer’s Quarters/Fairbanks Cottage had an interesting evolution, from a stone structure to a French Second Empire-style girl’s dormitory to a 20th century Junior High School. A portion of the original stone building remains intact inside the present structure, now bricked over. The stone projects a good 6 inches or so from the vertical wall plane, as do the eaves above. This extra depth is perfect for a single layer of 4” wide brick veneer.

3. Arsenal in Rome, New York

An arsenal was constructed in Rome, New York in 1813. It remained in operation until 1873. The home of the commandant is the only known structure remaining. It was sold to the private sector after the arsenal closed. It has sixteen rooms with ten fireplaces, elaborate plaster cornices and ceiling medallions, hand-hewn beams held in place with wooden pegs and a two and a half story open staircase. It is of the Federal style as characterized by the general proportions, a pediment on the main elevation, steeped walls with chimneys, casement windows on ground floor rooms, and a pair of oval windows at the gable end. It was divided into four apartments for many years. It has, at some point since its 1974 placement on the National Register of Historic Places, been renovated into a privately owned home.

4. Allegheny Arsenal

Construction of the Allegheny Arsenal began in April of 1814 in what was then Lawrenceville, Pennsylvania. The father of composer Stephen Foster was the developer of Lawrenceville and was the seller of the land to the federal government. Lawrenceville was annexed by Pittsburg, PA a few years after its founding. A portion of the arsenal ceased operation in the early 1900s and this was leased to the City of Pittsburg to become Arsenal Park. This portion of the site was transferred to city ownership in 1913.The other portion of the arsenal was auctioned by the federal government in 1925 to the private sector. The architect Henry Benjamin Latrobe and bridge engineer Thomas Pope were the designers of the first buildings constructed at the arsenal site. It should be noted that on the afternoon of Sept. 17, 1862, an explosion had occurred in one of the rifle and pistol ammunition production buildings at the arsenal. Seventy-nine workers were killed and many of the survivors were injured. One of the magazines of the remains of that arsenal was converted into restrooms for the public and workspace for park staff. Three industrial buildings of the arsenal and one Officer’s Quarters building were still standing in the early 1970s and being used for commercial purposes by private owners. Some of these buildings may still be standing.

5. Arsenal in Indianapolis, Indiana

In 1862, Congress passed an act to create a permanent U.S. Army arsenal in Indianapolis, Indiana, and construction was begun in 1863. The arsenal remained in operation until 1903. Winona Technical College bought the site at auction in 1904, but lasted only until 1910. At the time, the Indianapolis Public School system was in great need of a third high school. The Indianapolis Public Schools obtained possession of the buildings and opened Arsenal Technical High School in 1912. The Guard House, Main Arsenal Building, a barn converted into a classroom building, an Officer’s Quarters building, a barracks, and a powder magazine are the structures remaining from the arsenal and are still used by the high school. The high school complex includes many buildings constructed by the school system since 1912.

6. Dearborn Arsenal

An arsenal built in Detroit, Michigan, was closed in the early 1830s and a new site built in Dearborn, also in Wayne County MI, in 1833. The Commandant’s Quarters at the Dearborn Arsenal is a square, Federal style frame building standing on a raised brick foundation. Brick walls rise to a slate, hipped-roof that is broken by gabled dormers and surrounded by a balustrade. A two-story, square columned verandah wraps around the entrance and side facades of the building. The Commandant’s Quarters is one of three remaining structures out of the eleven original buildings at the arsenal site. The Commandant’s Quarters served as the social center of life at the complex and later served as a library, a town hall, and a newspaper office. Purchased by the Dearborn Historical Commission in 1949, the building was restored in 1959 and currently houses the Dearborn Historical Museum.

After the closing of the Arsenal in 1875, the Powder Magazine, along with six acres, was purchased by Nathaniel Ross in 1883. It was converted into a home. In 1950, Miss Mary Elizabeth Ross, the last immediate member of the family, passed away. Her will designated that her home and property be left to the City of Dearborn for a museum honoring both her mother and father. In 1956, the McFadden-Ross House was opened as the second building of the Dearborn Historical Museum. The McFadden-Ross House features exhibits, a meeting room, and an archive that includes genealogical resources and a wide range of photos, papers and books.

The Sutler’s Shop of the Dearborn Arsenal still stands as a structure in commercial use at the northeast corner of Garrison and Monroe streets. The Sutler provided services and products similar to what the Post Exchange and Commissary do today on Armed Forces installations. Items such as soap, razor blades and tobacco were available at the Sutler’s Shop. It was built in 1833 with slate roof, walnut timbers, and brick walls.

7. Arsenal at Harpers Ferry, West Virginia

The arsenal at Harpers Ferry, West Virginia (Virginia prior to June 20, 1863) had all of its production facilities destroyed in the Civil War. Given the magnitude of the destruction, the Ordnance Department decided to abandon the armory site. This decision coincided with a general shift in the government’s focus to the rapidly developing territories west of the Mississippi River. In May of 1866, Chief of Ordnance Dyer informed the Secretary of War: “Harpers Ferry cannot, in my opinion, be ever again used to advantage for the manufacture of arms, the retention of the property of the United States at that place is not necessary or advantageous to the public interest…and I recommend that…all the public land, buildings, and other property there be sold.” Its remaining residential structures and the building the fire engine had been stored in were sold to private firms after the Civil War ended. The Army had sold several residential structures to workers prior to the start of the Civil War. The foundation of the Rolling Mill built in 1853 was reused for a hydro-electric power plant that operated from 1925 to 1991.

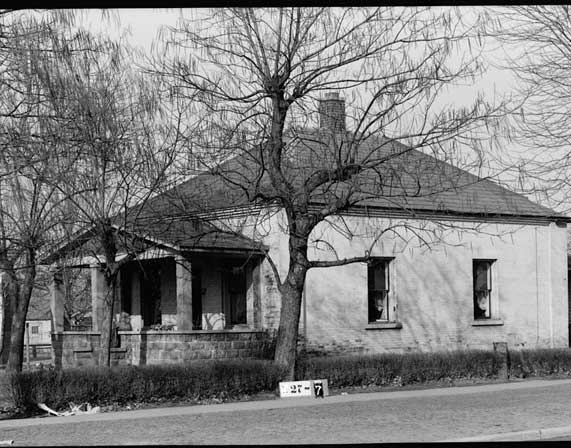

8. Pikesville, Maryland Arsenal

The first buildings of the Pikesville, Maryland Arsenal were constructed between 1816 and 1818. The facility was closed by the Army in 1879 and transferred to the State of Maryland in 1880. The complex was operated as a home for Confederate States of America veterans from 1889 to 1932. Daniel Murray Key, a veteran of the Confederate Army was a resident of the home and died there in 1913. He was a grandson of Francis Scott Key, the author of the Star Spangled Banner. In 1936, the Maryland legislature placed the property under the supervision of the Arsenal and Veterans’ Memorial Commission. The members of the Pikesville Volunteer Fire Company helped to maintain the property and the Boy Scouts, Red Cross, and a Health and Recreation Center established headquarters in the most usable buildings.

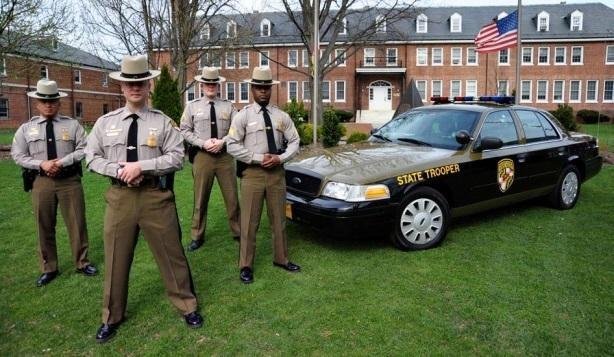

At the close of World War II, when it became apparent that the Maryland State Police would have to consider moving from the Pikesville Military Reservation (which they occupied on a loan basis during the wartime absence of the National Guard), Colonel Beverly Ober, superintendent of the Maryland State Police, introduced the idea of renovating the Old Soldiers’ Home property for the use of State Police as a headquarters.

Rehabilitation was begun in 1949 and on September 9, 1950, the former federal arsenal and Maryland Line Confederate Soldiers’ Home officially became headquarters for the Maryland State Police. The Maryland State Police uses the Arsenal Commandant’s home and one armory building as part of its headquarters. These buildings are adjacent to a number of modern structures on the site. All but one other structure from the arsenal were demolished in the period between 1880 and the 1950s. The Pikesville Kiwanis Club has, since 1949, owned and maintained as its headquarters a storage bunker made of stone. The club put a new roof on the building and removed the inner magazine walls to turn the building into meeting space. The Pikesville Arsenal Powder Magazine is a rectangular building originally constructed with an inner magazine and protected by outer stone walls. The windows were placed in formerly filled-in embrasures made of lightly attached stone or brick infill that would blow out in case of an explosion (thus leaving the main walls standing). The building was formerly lined with wood sidewalls. All fastenings were countersunk and wood-plugged to avoid a possible spark. The pintles were of bronze.

9. Bellona Arsenal

Bellona Arsenal was built in Chesterfield County, Virginia. The arsenal quadrangle originally consisted of eight buildings. The arsenal was constructed between 1815 and 1817 to receive cannons built by the adjacent foundry operated as a private firm by Major John Clarke. Secretary of War John C. Calhoun responded to concerns of the Governor of Virginia about the vulnerability of the arsenal to slave revolt or other civil disturbance. He stated in an 1823 letter that he was ordering an increase in the number of soldiers assigned to the site and that the muskets stored there not assigned to soldiers would be without flintlocks, rendering them useless if seized. The nearest active duty installation of the U.S. Armed Forces at that time was Fort Monroe in Hampton, Virginia.

In 1833 the arsenal was closed with one government employee kept on site as a caretaker. The arsenal was closed because of the rate of illness among the staff. An 1840 U.S. Army report on medical statistics mentioned the following.

At Bellona Arsenal, near Richmond, intermittent and remittent fever prevailed, as usual, to a great extent. Although the fatal cases were few in number, nearly all were attacked, and recovery was exceedingly slow in consequence of relapses. The locality being regarded very insalubrious, it was recommended that the troops form an encampment, a few miles from the post, during the summer months. The good effects experienced from this measure at Fort McHenry, and the partial advantage at the arsenal near Augusta, Ga., were urged in its favor.

From 1837 to 1842, Thomas Mann Randolph and a business partner leased several of the buildings for use as a silkworm farm. In 1856, the grandson of Major Clarke purchased the entire arsenal property. The combined arsenal and foundry site was listed in an August 15, 1862 letter from George Minor, Commander Chief of Ordnance and Hydrology Bureau of the CSA Navy, in which Minor said “Smoothbore and rifled cannon are being made at Bellona and Tredegar’’. On January 1, 1863, Archer leased the arsenal and foundry sites to the Confederate Government and remained on as Superintendent. The unsuccessful raid attempt by Union Army forces under the command of Colonel Ulric Dahlgren in March of 1864 included these instructions: “Pioneers (“Sappers” in the modern U.S. Army) will go along with combustible material. Men will stop at Bellona Arsenal and destroy it.’’ Three of the Arsenal Workshops remain, with all other structures having been demolished in the mid-1870s to early 1900s era. The Commonwealth of Virginia considered acquiring the site in the early 1870s and converting the buildings into the core of a new State Penitentiary. The plan was canceled, so the State Penitentiary remained in operation until 1992 in Richmond, VA. Two of the buildings were, in the 20th century, converted from mere shells into one residence linked by additions. The third building was converted into a guest house.

10. Arsenal in Little Rock, Arkansas

An arsenal operated in Little Rock, Arkansas from 1838 until 1892. The land became a park in the City of Little Rock. The park was known as City Park but was renamed MacArthur Park in1942. The Arsenal Tower is the only building still standing. The Old Arsenal is a two-story, brick, rectangular structure 122 feet long and 42 feet wide, with a full basement. Its two 3-bay wings flank a four-story crenelated tower, octagonal in shape and 25 feet in diameter. The tower projects from the center of the north side of the building and is entered from a single centered door. A two-story veranda runs along the north side from both ends of the building to the octagonal tower in the center of the structure. On the south side, a wood veranda runs the full length of the first floor, the roof being supported by braced wood columns spaced approximately 17 feet on centers. Gen. Douglas MacArthur was born in 1880 in one of the rooms on the second floor of the building, which then formed the officers’ quarters at the post. His father, Arthur, was a captain at the time. Arthur would retire as a Lieutenant General in 1909. The museum presently known as the Museum of Discovery in Little Rock was located in the building from 1942 to 1997. The MacArthur Museum of Arkansas Military History has used the building since the Spring of 2001.”

11. Chattahoochee Arsenal

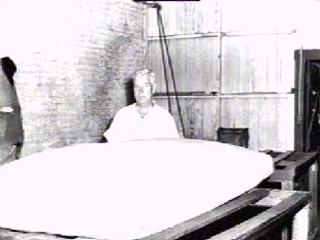

Chattahoochee Arsenal was constructed in Gadsden County, Florida, between 1835 and 1839 to provide the Army with logistical support in handling potential military action if further conflicts with Native Americans were to occur in the region. There had been two wars with the Seminole Tribes and groups of escaped slaves in the 1816-1835 period. The arsenal, consisting of thirteen buildings, was captured from the U.S. Army by State of Florida militia forces on January 6, 1861, four days before the state of Florida seceded from the Union. The facilities were not used by the Confederate States Government or the State of Florida during the Civil War. After the Civil War, the U.S. Arsenal at Chattahoochee was again federal property. It was transferred to the Freedmen’s Bureau in 1866. The arsenal buildings had been stripped by local residents who took anything of value. In 1868, the U.S. arsenal property at Chattahoochee became Florida’s first penitentiary. In 1876, inmates were relocated from the Chattahoochee prison. Then the site and buildings were converted into Florida’s first Behavioral Health Hospital, now known as Florida State Hospital.

One powder magazine from the arsenal became a mattress factory, operated using patient labor. In November of 2013, the Powder Magazine was rededicated as a museum and conference center. The Officers’ Quarters was a Masonry Vernacular construction with a two-story brick main building and one-and-a-half-story wings, plus carved bracketing and framing of the front and rear porches. It still stands as an administration building of the hospital. All other structures from the arsenal have been demolished.

12. Mount Vernon Arsenal

Mount Vernon Arsenal was constructed by the U.S. Army from 1830 to 1835 in Mobile County, Alabama. The arsenal operated under federal control until January 4, 1861, when it was captured by forces from Mobile who were sympathetic to the Confederacy. After the Civil War ended, it was returned to federal control and ceased to be designated as an Army Arsenal in 1873. It remained in use as a base of the U.S. Army until the Spring of 1894. In 1895, the site and structures were transferred to the State of Alabama by a bill signed by the President after being passed by the U.S. House and Senate. Mount Vernon, later renamed Searcy Hospital, opened as a Behavioral Health and Intellectual Disabilities hospital for African American patients in 1900. The hospital was desegregated in 1969 and closed in 2012. Thirteen buildings from the arsenal remain on the site which awaits an adaptive reuse.

As a point of interest, it should be noted that Josiah Gorgas, the Chief of the Ordnance Corps of the Confederate States of America, was the Commandant of Mount Vernon Arsenal in the mid-1850s. He was born in Pennsylvania and was an 1841 graduate of the U.S Military Academy at West Point. While he was Commandant, he married Amelia Gayle, daughter of Judge John Gayle, a former governor of Alabama. His son, William Crawford Gorgas, was born in Alabama while Josiah was Commandant of Mount Vernon Arsenal. William became a U.S. Army doctor whose medical research and public health efforts controlled the number of Malaria and Yellow Fever cases during the construction of the Panama Canal.

13. Baton Rouge, Louisiana

A site in Baton Rouge, Louisiana served as a military base for governments such as France, England, Spain, West Florida, the United States, Confederate States of America, and again the United States, from 1779 to the 1870s. A major expansion of the post was made in 1819-1823 when new barracks were built and a large arsenal depot was established to serve the southwestern United States. The base closed in 1877 when the last federal troops in the state for the Reconstruction Era purposes departed the state. The base was transferred to the State of Louisiana and was used by Louisiana State University from 1886 to 1925. Today, the Pentagon Barracks houses the offices of the Lieutenant Governor as well as private apartments for state legislators. A powder magazine, built in 1838 as part of the arsenal on the base, stands today as the Old Arsenal Museum operated by the State of Louisiana government. It was built to hold 3,000 barrels of powder. From 1879 to 1886, the magazine was rented to private companies for powder storage. When the former base was the campus for LSU, the Magazine was used for training the students in Military Science. After LSU vacated the site, the Magazine was used as National Guard quarters and as a State Police pistol range and storeroom. It was not used for any purpose during or after World War II until it was renovated to become a museum in 1962.

As we’ve just seen, thirteen of the twenty-seven Ordnance Corps facilities built before 1865 were closed and transferred to state or local governments or the private sector for other uses before 1914. Several others of the 27 facilities were converted to other uses by the Armed Forces or other federal agencies prior to World War I. The Washington, DC Arsenal was closed in 1881 and transferred to the Quartermaster Corps. The site is now Fort Lesley J. McNair of Joint Base Myer-Henderson Hall.

Today, the past is ready to repeat itself. The Army and the Department of Defense are in a major transformation phase. Undersecretary of the Army Brad R. Carson, in a 2014 speech, stated: “The Army stands at a critical moment in its history, challenged to reshape into a leaner force still capable of meeting the nation’s strategic priorities.” Secretary of the Air Force Deborah Lee James said the following in a February 2014 speech.

The Department of Defense is going through a transition period following thirteen years of war, and will be making tough choices as personnel and budgets dwindle and the possibility of sequestration looms during the years ahead. We are repositioning to focus on the challenges and opportunities that will define our future… We have to get ready for the new centers of power, such as the Pacific, and what will be a more volatile and unpredictable world, a world we can no longer take for granted.

Katherine Hammack, the assistant secretary of the Army for Installations, Energy and Environment, testified to the Senate Armed Services Committee on April 2, 2014, that the Army needed to close more installations. Hammack addressed the Army’s reduced force structure and the impact it would have on infrastructure. With the end of ground combat operations in Iraq and Afghanistan, the Army will be on a path to shrink its active-duty end strength. She informed the Senate of the desire of the Army for a Base Realignment and Closure Commission (BRAC) to be formed in 2017.

Inside the United States, the best and proven way to address excess and shortfalls in facility requirements in a cost-effective and fair manner is through the BRAC (base realignment and closure) Commission process… The Army continues to need additional BRAC authorization to reduce excess infrastructure effectively… As the Army’s end strength and force structure decline alongside its available funding, hundreds of millions of dollars will be wasted maintaining underutilized buildings and infrastructure.

There are examples of facilities disposed of in the post- World War II era to the present . 13 of the structures of the World War II era New River Ordnance Works in Pulaski County, Virginia were sold to the private sector in 1948 and 12 continue in commercial use today. The Pump House served the first commercial owner of the other buildings and is now leased by the Town of Pulaski to the Coast Guard Auxiliary. The Lone Star Army Ammunition Plant in, Texarkana, Texas was closed as a result of the 2005 BRAC process and sold to the contractor that operated it. The contractor continues to operate the facility. The Riverbank Army Ammunition Plant in California was also closed in 2010 through the 2005 BRAC. It was transferred to a locality operated development agency that leases the facility to a number of manufacturing and services firms. Three buildings of the former Volunteer Army Ammunition Plant in Hamilton County, Tennessee are used by the school system as offices and training space. The plant had ceased manufacturing operations in 1977 and transfers of parcels from Federal ownership began in the 1990s. Most of the site has become an Industrial Park with new structures including a Volkswagen auto manufacturing plant.

There are programs for not in use structures and land that remain in Army ownership. The Army’s Enhanced Use Lease Program (EUL) engages private sector entities through a competitive process to develop underused but not excess Army real property for purposes that are compatible with an installation’s mission and which serve the public interest. The U.S. Army Retooling and Manufacturing Support (ARMS) ARMS program is a public-private initiative designed to encourage facility contractors at government-owned, contractor-operated ammunition plants to use and market idle capacity for other government and commercial work. This includes private firms building new structures as part of their lease to utilize excess infrastructure capacity for their operations or using underutilized infrastructure of the installation as the core of their operations as in the instances of a rail services firm using portions of installation’s rail system to repair freight cars and operate a bulk materials rail to truck transfer facility.

Facilities are not simply transferred to states or localities by a bill passed by the House of Representatives and Senate then signed by the President as the arsenals closed before 1914 were if auction to private sector was not the disposal method. The current transfer process to a State or Local/Regional Agency involves the creation of a locality or state government based Local Reuse Authority (LRA). The LRA serves as a coordinating body for the community and is responsible for preparing and implementing the redevelopment plan. Additionally, the LRA works directly with Office of Economic Adjustment (OEA) project managers and the military services to help with this process. The LRA is also the single community point of contact for all matters relating to the closure or realignment. Auction to the private sector is still used to dispose of individual buildings or small installations in some instances.Former government owned ordnance production and maintenance sites will continue to be transformed into productive uses with or without the buildings remaining, many in similar ways to the first reused sites.

All photos are provided by the author.