War History online proudly presents this Guest Piece from Jeremy P. Ämick, who is a military historian and writes on behalf of the Silver Star Families of America.

Many stories from World War I have not survived the passage of time since the United States was involved in the war for such a short period. By the time many local residents of military service age were inducted and trained, the armistice had already been signed. But for two stepbrothers from Elston, such delays did not keep them from the conflict since they enlisted early to serve their country.

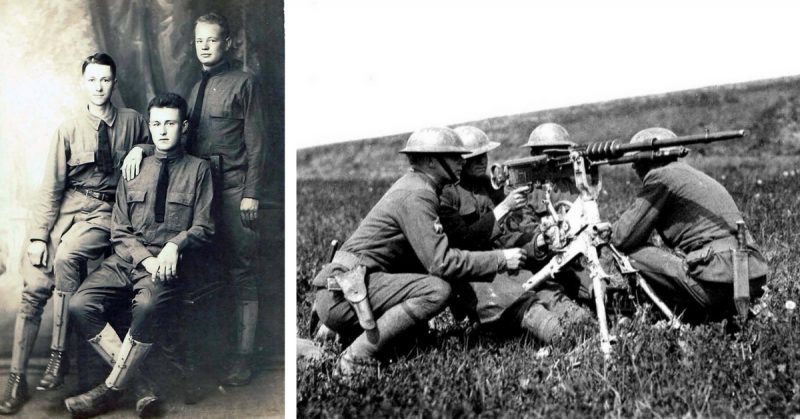

Born November 25, 1898, Homer McCrea lost his father at a young age. His mother then married widower George Landrum in 1905, uniting two families and creating a close bond between the young McCrea and an older stepbrother, Luther Landrum.

“Luther and Homer got this idea in their heads that they would run off and join the Army,” said Jean Christian, niece of the late veterans. “I know very little about their time in the service,” she added, “because it’s not something that was really discussed.”

As is woven into family lore, Christian explained, the stepbrothers snuck away to Jefferson Barracks, Missouri, to enlist in the Army. Shortly thereafter, their father took a train to the army post in an effort to have his sons released from service; however, he was too late.

Service cards accessed from the Missouri Sate Archives verify that both Landrum and McCrea enlisted at Jefferson Barracks on May 9, 1917, approximately a month after the official declaration of war was made by the United States.

Though the date of their enlistment indicates the two intended to serve in the same military unit, the needs of the Army soon placed them on separate paths—Landrum was assigned to Company A, 1st Machine Gun Battalion of the1st Division while his step brother was eventually assigned to Company K, 61st Infantry of the 5th Division.

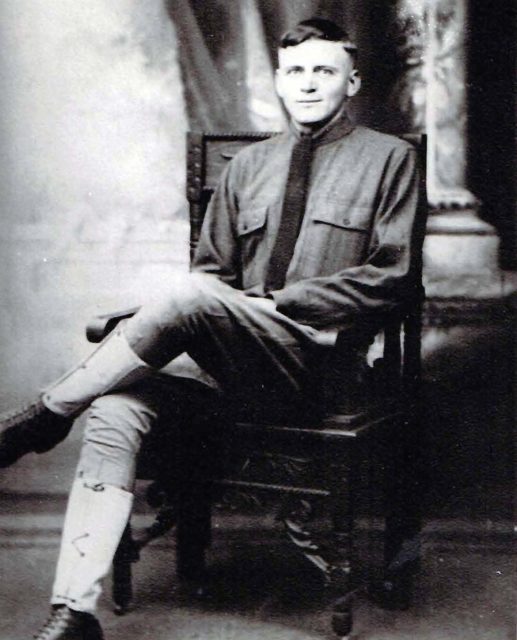

A 22-year-old Landrum’s adventure began in earnest on October 31, 1917 upon his arrival overseas. As written in the “History of the First Division,” the machine gunners were soon issued the “Hotchkiss”—a type of machine gun used by the French and adopted by the Americans.

They soon began a brief cycle of training on the weapon followed by drills that consisted of “selecting and occupying positions and in serving the guns against an imaginary enemy position,” the book further described.

Landrum and his fellow soldiers were to soon risk life and limb during some of the most hellacious epidoses of the war, which included winning “the first American victory in World War I at the Battle of Cantigny,” on May 28, 1918, noted the First Division Museum at Cantigny.

In later weeks, the museum shared, “the First Division participated in the major battles of Soissons, St. Mihiel and the Meuse-Argonne,” the latter of which earned the young Landrum recognition that he chose to conceal from his family for several years after the war’s end.

Pvt. Homer McCrea remained stateside for nearly six months following his step brother’s deployment, leaving his training at Camp Greene, North Carolina, to join the battle waging in Europe alongside the Fifth Division in mid-April 1918.

The horrors of trench warfare soon became a reality for McCrea as the soldiers of the division battled not only a well-entrenched German foe and filthy living conditions, but also endured unmerciful shelling along with heavy bombardments of mustard and phosgene gasses.

McCrea also participated in St. Mihiel and the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, during which mere survival became a triumph of its own accord. As the Society of the 1st Infantry Division notes on their website, although the men fought valiantly and overcame insurmountable odds, “(b)y the end of the war, the Division had suffered 22,668 casualties.”

In the face of these tremendous odds, both McCrea and Landrum survived their baptism of fire during a war that resulted in the loss of more than 116,000 American troops in less than two years. When the conflict ended with the armistice of November 11, 1918, the step brothers remained in Europe with their respective divisions as part of the Army of Occupation.

Sadly, having survived months of German assaults that resulted in the death of many of his comrades, Sgt. McCrea died on February 17, 1919 from what is listed on his service card as “pneumonia”; however, the deadly Spanish Influenza epidemic was also sweeping through American military camps during this period.

Five days after the passing of his younger step brother, Private Landrum left Germany, departing for home six months prior to the remainder of the 1st Division’s return to the states.

“I don’t know if Luther came home on a hardship because of Homer’s death,” said Christain, “but considering the timing, that was likely the case.”

McCrea’s body was eventually returned to his family and interred in Elston Cemetery, said Christian. In the years after the war, Luther married, raised a family and worked as farmer in Mid-Missouri. As he reached his final years, he moved to Georgia to live with his daughter, where he passed away in 1992.

“Luther Landrum, a son of George Landrum of Elston, was cited for bravery during the operations of the American Army west of the Meuse from October 4 to 12, 1918,” reported the February 28, 1922 edition of The Daily Capital News, thus revealing a secret Landrum had maintained.

The article went on to describe the three citations he received for bravery for his action in loading and firing a machine gun from an exposed position while under the constant threat of enemy shell and machine gun fire.

“He came home safe but his brother came home in a casket,” said Christian. “Homer’s death was hard on him and that’s why he tried to keep his awards secret.”

She concluded, “Nothing was shared about Homer because his death was so devastating on the family and on Luther. I think that if you can use their pictures to connect a face with their service papers and a little bit of history, then it really humanizes the sacrifice that they made; it helps ensure that what they went through won’t so easily be forgotten.”