War History Online presents this Guest Article from by Joseph M. Durante

“Gaul comprises three areas…” and “the whole of Gaul was now conquered.”

In 58 B.C. the military commander, politician, and aristocrat Gaius Julius Caesar waged war in Gaul and for six years tried to conquer the region and submit them to Roman control. By September of 52 B.C., Caesar was about to conquer of all of Gaul with one final siege and battle, the Siege of Alesia. Julius Caesar is easily one of the most well-known Romans and it was his military conquests that established his name as one of the greatest military commanders in history. His siege of Alesia, know as the circumvallation of Alesia, is what really set the mark on how intelligent he was regarding military stratagems. With his victory at Alesia, all of Gaul became under Roman control and paved Caesar’s path to glory.

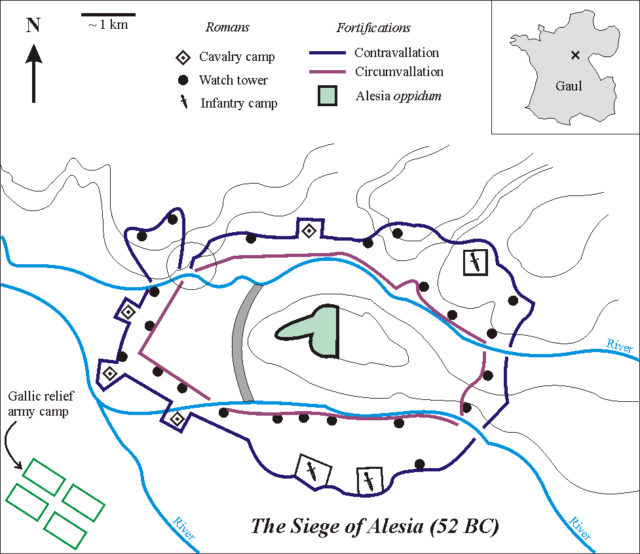

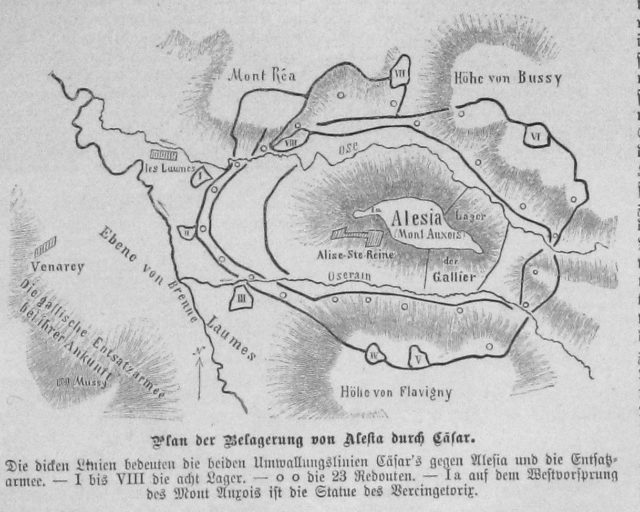

The most important detail of this battle is to explain exactly what circumvallation is. Circumvallation is a military strategy used to siege a fortified position–cities, towns, villages, forts, and camps. This requires the army laying siege on a fortified position to construct siege equipment that covers the area of the fortified position. Usually, placing barracks with ramparts assigned to infantry with enough supplies to outlast the people inside the fortified position is key to a successful siege. Of course, the army laying siege must not allow anyone or anything to enter or leave the fortified position, because there can be no relief aid to the people inside. Some might wonder, though–why not just storm the city? Caesar knew a full frontal assault would produce heavy casualties and compromise victory over the Gauls, writing, “it was clearly impregnable except by blockade,”and that the city was on a hill of high altitude, with streams to the north and south, surrounded by hills on the north, east, and south sides.

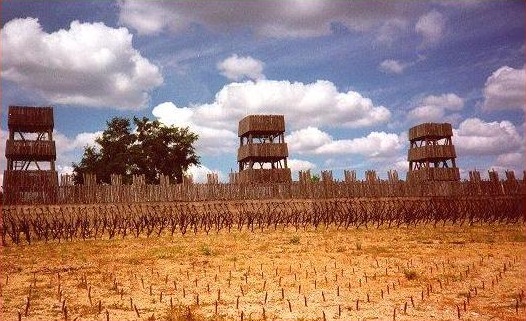

This strategy is common among many sieges because it is a necessary factor in achieving victory. The circumvallation siege is supplied with infantry to defend if the enemy leaves the fortified area to try and break the siege. Artillery is used to help siege the area, such as ballistae, onagers, catapults, archers, all of which are to help suppress the actions and protect the siege machines.

But Julius Caesar’s siege was a little different than the definition discussed above. Caesar surrounded the city of Alesia with ramparts and infantry, but also built another set of walls and ramparts facing outward, behind his legions. During the construction of the siege, the Gauls from inside the city attacked Caesar’s troops. Their leader, Vercingetorix, then Chieftain of all the Gauls, took command of the Gallic tribes in the same year.

The Gauls sent their cavalry to attack the Romans constructing the siege, and in response “Caesar committed his reserve of German horseman and formed up some of the legionaries in support,” which caused the Gauls to retreat back into the city. Vercingetorix, fearing entrapment within the city for good, “sent his cavalry away before the blockade was closed, telling them to return to their tribes and raise a relief army.” Once the wall facing inward was complete, Caesar immediately instructed his men to work on the wall facing outward, knowing that the cavalry who slipped through would come back with a relief force. In response to the siege being completed, Vercingetorix released all the women, children, elderly and ill from the city. By doing so, Vercingetorix now had fewer mouths to feed and ensured that the army’s food supply could sustainably feed his warriors.

Caesar, however, was not content to let the unarmed civilians through the siege, and so they were left to die in a kind of ancient no man’s land, stuck between both fortified armies. With the food now reserved for fighting men, Vercingetorix waited to attack Caesar so he could unite with the Gallic relief force. With the relief force in sight, Vercingetorix attacked the inner fortifications and the relief force attacked the outside fortifications. In response, Caesar “rush[ed] reinforcements to threatened sectors and at times led counterattacks against the enemy flanks,” leading the Romans to victory and pushing the Gallic force to surrender. Vercingetorix himself surrendered, warriors became war captives, and all of Gaul was soon under Roman control. Vercingetorix was captured, “kept in chains reserved for Caesar’s eventual triumphal procession, for six long years,” and “in 46 B.C. his shrunken frame was dressed once more in his best armor; and after being paraded in Caesar’s triumph Vercingetorix, a prince of Gaul, was ritually strangled.”

According to Caesar himself, he had his men build eight camps that were connected by fortifications along with twenty-three redoubts. As mentioned earlier, Vercingetorix sent messengers to call for relief before the Romans could finish their fortifications. To help fight against surprise attacks, Caesar ordered his men to dig trenches all over the land in between Alesia and Caesar’s fortifications. The Romans also installed sharpened branches inside those trenches to impale any enemies that fell into them. Caesar also had his men dig smaller holes in the ground, fitted for one person with sharpened branches protruding towards the middle of the hole and covered the hole with branches and brushwood to hide the trap. As a result, when someone would fall into it, the branches would impale their legs and lower body and when they would try to climb out of the hole, the branches would shred their bodies. When these fortifications were finished, Caesar constructed the outside walls and fortifications to defend against the relief aid. These fortifications were fourteen miles long, located on the flattest ground around Alesia. With the inner wall now finished, they were able to protect the Roman siege workers working on the outside wall from Vercingetorix’s cavalry.

The importance of this siege is to show that ancient warfare was extremely tactical and that stratagems had to be deployed to obtain victory in war. This siege demonstrated the level of intelligence that Caesar had regarding military leaderships. Caesar would later go on to fight a civil war against his long time friend, ally, and co-consul Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (Pompey the Great). With a victory against Pompey and the Senate, Caesar became sole political leader of the Roman Republic and became Dictator for ten years, and before his assassination, he was named dictator for life.

Gallic Forces Inside Alesia:

- Vercingetorix – 80,000

Gallic Military Relief Forces:

- Aedui (included, Segusiavi, Ambivareti, Aulerci, Brannovices, Blannovii) – 35,000

- Arverni (included, Eleuteti, Cadurci, Gabali, Vellavii) – 35,000

- Seguani – 12,000

- Senones – 12,000

- Bituriges – 12,000

- Santoni – 12,000

- Ruteni – 12,000

- Carnutes – 12,000

- Bellovaci – 10,000

- Lemovices – 10,000

- Pictones – 8,000

- Turoni – 8,000

- Parisii – 8,000

- Helvetii – 8,000

- Suessiones – 5,000

- Ambiani – 5,000

- Mediomatrici – 5,000

- Petrocorii – 5,000

- Nervii – 5,000

- Morini – 5,000

- Nitiobroges – 5,000

- Aulerci Cenomani – 5,000

- Atrebates – 4,000

- Veliocasses – 3,000

- Aulerci Eburovices – 3,000

- Rauraci – 1,000

- Boii – 1,000

- Aremorican (included, Coriosolites, Redones, Ambibarii, Caleti, Osismi, Veneti, Lexovii, Vanelli) – 20,000

- Bellovaci – 2,000

- Army Strength – around 256,000 infantry and 8,000 cavalry strength

Julius Caesar and Roman Army Strength:

- Roman legions – 50,000

- 5th Alaudae Legion

- 8th Augusta Legion

- 9th Hispania Legion

- 10th Fretensis Legion

- 11th Claudia Legion

- 12th Fulminata Legion

- 13th Gemina Legion

- 14th Gemina Martia Victrix

- Auxiliary infantry and cavalry – 30,000

Bibliography

- Caesar, Julius. The Conquest of Gaul. Translated by S.A. Handford. England: Penguin Books, 1951.

- Penrose, Jane, ed. Rome and Her Enemies: An Empire Created and Destroyed by War. Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2008.

- Goldsworthy, Adrian. Caesar: Life of a Colossus. United States: Yale University Press, 2006.

- Goldsworthy, Adrian. The Complete Roman Army. London: Thames and Hudson Ltd, 2004.

- Dando-Collins, Stephen. Caesar’s Legion: The Epic Saga of Julius Caesar’s Elite Tenth Legion and the Armies of Rome. Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons, Inc., 2002.

- Dando-Collins, Stephen. Legions of Rome: The Definitive History of Every Imperial Roman Legion. New York City: St. Martin’s Press, 2010.