War History online proudly presents this Guest Piece from Jeremy P. Ämick, a military historian, and author of the upcoming Arcadia Publishing book “Missouri at War.”

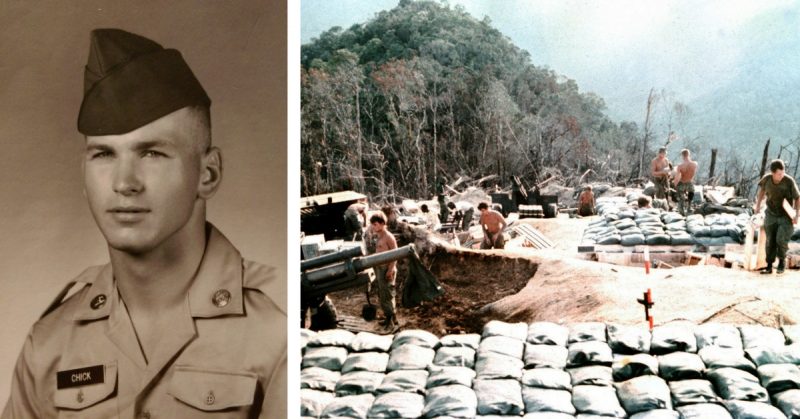

For several decades, Mike Chick has struggled with health issues related to his combat service with the Army but only recently discovered the resources that are available through the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) for those who served in Vietnam. Now, using his own experiences from the war, Chick strives to connect with fellow veterans who are often unaware of their eligibility for such benefits.

“I was diagnosed with diabetes when I was 32 years old and never realized that it was somehow related to what we had been exposed to in Vietnam,” Chick said.

He added, “It wasn’t until attending a veteran’s event in Branson several years ago that I spoke with a veterans’ service officer and he told me that I could be entitled to benefits from the VA.”

A 1968 graduate of Helias High School, Chick explained that he worked construction for a few months following his graduation until he and his friend, John Prenger, decided to enlist in the U.S. Army and “get it over with instead of being drafted,” he said.

Following their enlistment under the “buddy program” in September 1968, Chick and Prenger completed their basic training at Fort Leonard Wood; however, the friends were soon separated when Chick received orders for infantry training and Prenger was assigned to the artillery.

“I guess I proved myself to be too good a rifle shot in basic training,” he joked, when discussing his assignment to the infantry.

For the next eight weeks, Chick attended advanced infantry training at Fort Ord, Calif., followed by his receipt of orders for service in Vietnam. Boarding a plane at Travis Air Force Base, Calif., the soldier arrived at Long Binh, Vietnam, in January 1969. He then completed a week of jungle training and was assigned to 3/60th Mobile Riverine Force.

“We operated off of a big Navy ship on the Mekong River,” Chick recalled. “For several months, twenty or so of us soldiers would leave the ship on Tango boats and go downriver on five-day operations.”

He continued, “They gave you a map that showed you where to go and we would chase the Viet Cong (VC) through the jungles on search and destroy missions. Sometimes, we would also search villages for the VC,” he added.

On one mission, Chick recalled, several of his fellow soldiers were wounded and others killed when a member of their group tripped a booby-trapped 105mm round.

“We had to pick one guy up with a poncho who had lost part of his leg and arm after the round exploded,” Chick said. “That’s the kind of stuff that I got to see up close and personal while I was over there.”

Three months after his assignment to the riverine forces, the soldier learned the 3/60th would be one of the first groups to return to the United States, but since Chick had only three months of combat duty behind him, he was reassigned to Company K, 6th Battalion, 31st Infantry located at Dong Tam nearly 40 miles south of Saigon.

“We were basically doing operations the same way—chasing ‘Charlie’ through the jungle,” he said. (“Charlie” was a slang term used by American soldiers to describe the VC.)

On the morning of July 31, 1969, Chick recounted, he and a group of soldiers were patrolling along a dike between rice paddies while guarding the perimeter of Dong Tam. It was during this patrol that Chick unknowingly stepped over a booby trap.

“The guy behind me—Robert Roberts, who had been a football player in Texas—stepped on the booby trap and it exploded.” He solemnly added, “It blew me forward and (Roberts) up in the air. He ended up losing his left leg and I had shrapnel in my hip and calf.”

The men were evacuated to a Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (MASH) where, after Roberts “quit breathing for about the third time,” Chick said, he watched from his hospital bed as the medical staff cut open his friend’s chest and massaged his heart.

“That’s a vision that just kind of sticks with you and you can never forget,” he bluntly asserted.

Chick was later transferred to a hospital in Japan and later sent to Ft. Sill, Okla., to undergo physical therapy and learn to walk again. He finished out the remaining months of his enlistment with a supply unit at Ft. Leonard Wood, leaving the Army in June 1970—three months early so that he could attend classes at Lincoln University in Jefferson City, Mo.

In later years, Chick was employed as a union sheet metal worker until retiring in 2007. He continues to reside in Jefferson City with his wife, Linda.

At a young age, Chick explained, he was diagnosed with diabetes and began treatment without knowledge of its connection to his military service in Vietnam. However, after being advised by a veterans’ service officer many years ago of the link between Agent Orange exposure and diabetes, he now receives treatment from the VA and continues to advise other veterans on the availability of such benefits.

“There are a lot of veterans out there who have absolutely no idea they are entitled to certain benefits from the VA,” Chick said. “Not too long ago I visited with a Vietnam veteran who had two open heart surgeries and diabetes, and he isn’t getting a dime.”

He humbly added, “It’s not so much about me wanting to share my personal experiences but rather to help make sure my fellow veterans understand the benefits that they have earned through their service, whether they served in World War II, Korea, Vietnam or in a more recent conflict.”