By Catherine Clement

Not every secret agent is flashy and well-dressed like James Bond. In fact, sometimes the most unassuming individuals prove to be the most skilled and daring of spies.

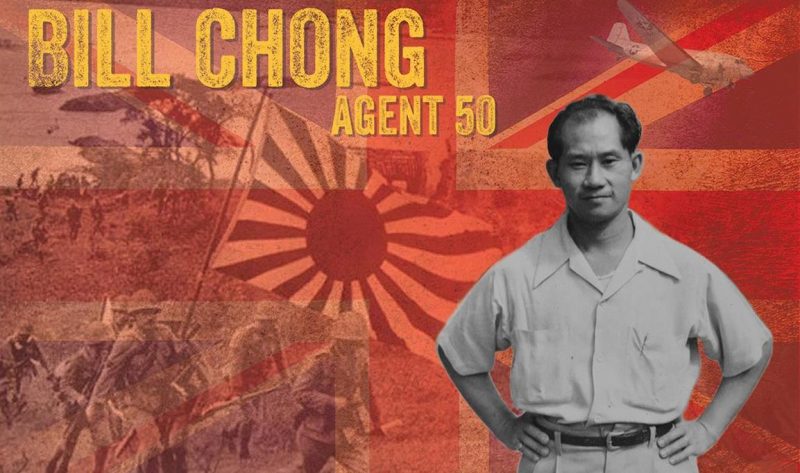

That was certainly the case for William “Bill” Gun Chong, a short, balding, unmarried, 30-year-old Chinese Canadian cook, who became one of the most successful British agents to operate in Japanese-occupied Hong Kong and China during WWII.

What led this high school dropout – with no training in weapons or espionage, who had been rejected by the Canadian Army – to end up with a British Empire Medal for bravery?

What gave Chong the ability to narrowly escape a beheading by a Japanese soldier? To break out from the locked hold of a fishing boat set adrift on the ocean? To negotiate his way out of being kidnapped by bandits?

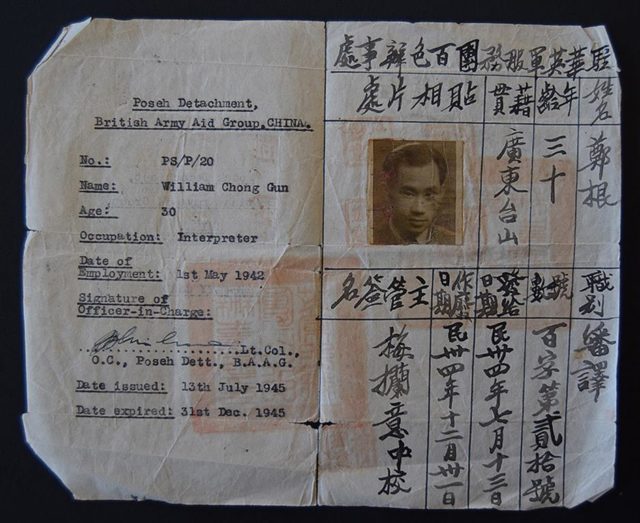

And what made Chong indispensable to the British Army Aid Group (BAAG) operating in China? An agent who not only served as an intrepid spy, but also as an adept courier, rescuer, guide, interpreter, surgical nurse, plumber and carpenter?

Unfortunate Circumstances:

Chong was born in Vancouver, Canada in 1911. He was raised when discrimination against Chinese was rife in Canada. Chong could note vote. He could not swim in public pools. And, although Canada was at war, men like Chong were initially spurned by the Armed Forces.

Chong was living life on the sidelines until a series of unfortunate events changed everything.

It was 1941, and while working as a cook and house servant in Vancouver, Chong learned his father had died. He set sail for Hong Kong to wrap up the estate.

However, the estate was more complicated than expected. Weeks turned into months. And on December 8, 1941, Chong found himself stranded in Hong Kong when the Japanese invaded.

The streets erupted in gunfire, blood and death. Hong Kong surrendered on Christmas Day. Chong was trapped.

While planning how to get back to Canada, Chong happened to peer over his balcony and noticed a severely injured Canadian soldier lying on the street, begging passersby for water. A group of Japanese soldiers stumbled upon him and one of the officers pulled out his pistol and executed the defenseless Canadian with a shot to the skull.

“I was full of hate,” Chong recalled years later. “I had seen how the Japanese killed people…they’d just shoot anybody they wanted.”

He decided then and there to flee to Free China and join the guerrillas.

Once in China, BAAG recruited him first. The innocuous sounding organization, purportedly created to dispense assistance to escaped POWs, was also a cover for espionage activities.

Chong was assigned a mission and given the code name Agent 50. To ensure the veracity of his messages, Chong would weave in reference to the number 50.

“I’d write I was going back for my mother’s 50th birthday. I’m waiting for

transportation. Things like that,” Chong explained.

Agent 50 became a master of disguise. He spent almost four years dressed in rags, passing himself off as a peasant. He mostly worked alone, and often walked 30-50 miles a day wearing only straw shoes.

“My only companions were mosquitoes, leeches and bedbugs” he once said. “There was no bus, no ferry, no bicycle, no horseback, no roads. Everything was by foot.”

As part of his act, Chong would walk with a limp and lean on a walking stick. The pole, which was hollow, was stuffed with intelligence information or medicines.

Escapes:

Chong lived in constant danger, traveling through enemy-held or bandit-infested territory. Three times he was captured. Three times he escaped.

On one of his first missions, Chong was arrested by the Japanese and locked into the cargo hold of a dilapidated fishing boat. The boat was set adrift on the ocean. Chong only survived when the boat captain – who was also locked in the hold – remembered the location of a rotting plank. The captain kicked at the plank, crawled out and opened the cargo hatch.

On another occasion, Chong was kidnapped by a group of bandits. He managed to negotiate his release after he offered to supply some hard-to-find medicine to one of the ailing kidnappers.

In the final close call, Chong, and a local guide he had hired, were discovered hiding by the Japanese. They were hauled out and interrogated between beatings.

Growing bored, one of the Japanese soldiers barked, “How do you want to die? By bullet or by beheading?”

“Shoot me,” Bill replied.

Both captives were ordered to dig their own graves. But the ground was hard: the digging slow. Growing impatient, the soldier yelled, “bullets cost money,” and raised his sword to behead the Canadian.

Just then, Chong’s guide started screaming something in Japanese. The soldier lowered his sword, reached into the guide’s pocket and found an old business card on which was the name of a well-known Japanese spy master turned army major. Impressed, and now worried these captives might be connected to someone in authority, both men were quickly released.

An agent with many talents:

Despite those harrowing experiences, there were many rewarding moments for Agent 50. In his time with BAAG, Chong managed to gather valuable information on Japanese activities.

He rescued and guided hundreds of downed Allied airmen to safe territory.

He saved thousands of lives, by risking his own, to smuggle life-saving medicines between remote BAAG field hospitals.

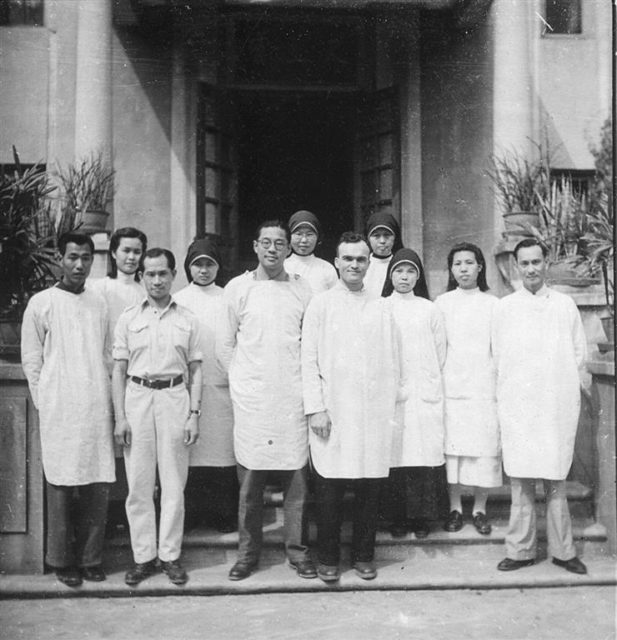

And, while resting between deliveries, Chong helped improve conditions at these medical outposts. One of the doctors described Chong’s contributions: “In addition to repairing various doors, furniture and the repainting of wood works and walls, he … completely overhauled the plumbing system of the hospital – a very difficult piece of job that had even baffled local plumbers.”

Probably the only task that made Chong lose his nerve was the first time he was asked to assist in surgery. Operations were undertaken in primitive conditions: usually in abandoned churches and schools. Often the room had windows but no glass, so flies were a constant problem.

Chong recalled the instructions he was given by the lead surgeon, “Bill, with your right hand, you soak the blood. And with your left, you fan the flies.”

Sounded simple enough until the first incision was made. Chong explained his reaction: “The first time I saw somebody cut up…I was stunned. Boy, I was shaking all over…afterward, when I finished for that night, I couldn’t sit down. I couldn’t stand up. I couldn’t go to bed. I didn’t know what I was doing.”

A hero:

Chong survived the war and vividly remembered the night he learned the conflict had ended

“I was so happy … I just sat down on the ground and cried,” he recalled. “I don’t know why. But I hope I served my country well.”

In 1947, Chong became the only Chinese Canadian to ever be awarded the British Empire Medal for bravery: the highest military honor given by the British government to non-British citizens.

Author: Catherine Clement.

Catherine Clement is the curator of the Chinese Canadian Military Museum in Vancouver, Canada. She recently designed an exhibition to commemorate the 75th anniversary of the invasion of Hong Kong.Clement is also working on a book about the amazing life and times of Bill Chong, Agent 50. For more information: Chinese Canadian Military Museum Society

All photos provided by the author.