War History Online proudly presents this Guest Piece from Dean Smith

Following the allied victory at the end of the First World War, the British newspaper the Daily Mail put forward a prize of £10,000 for the first non-stop crossing of the Atlantic by air.

The prize was won in 1919 by Alcock and Brown flying their Vickers Vimy, famously landing it in an Irish swamp (Nevin, 1993).

To commemorate the 50th anniversary of the transatlantic crossing, in 1969 the Daily Mail sponsored an air race between the UK and the USA, to cross the Atlantic, and return in the opposite direction.

The race was to take place between the tallest points on each side of the Atlantic, the Empire State Building in New York and the GPO tower in London (Dodworth, 2006).

Each side entered multiple aircraft in various categories. The US originally planned on entering their hypersonic bomber, the B58 Hustler. However, with the ongoing conflict in Vietnam, the commitment of military resources for such a publicity orientated display was politically inadvisable, as a result, it was withdrawn.

On the British side, the Royal Navy entered their F4 Phantom and the RAF entered a team flying the Victor Bomber. Surprisingly, the RAF also entered their new Hawker Siddeley Harrier, which had just entered service in April of that year.

There was a particular problem with this plan though. The Harrier was still going through testing before it entered service properly, it had only flown one two-hour sortie thus far, had carried out no air-to-air refuelling, it completely lacked the long-range fuel tanks necessary for transatlantic flight, and there were only three pilots capable of flying it.

The three men capable of making such a trip were Mike Adams, the RAF liaison pilot to Hawker Siddeley where they were based from the Dunsfold Aerodrome. Tom Lecky-Thompson, the primary project pilot, and Graham Williams, a pilot who by his own admission had spent “very little time on the aircraft” (Marston, 2015).

Adams was chosen as the primary pilot, with Lecky-Thompson being chosen to fly the second leg of the flight. Initially, Williams was in reserve. This was until an accident a few months before the race was due to commence when the nose wheel of the harrier Adams was taxiing in at the time, sheared off resulting in great injury to its pilot.

With Adams out of commission, it fell to the inexperienced Graham Williams to fill the gap and return the harrier back to London on the second leg of the race (Glancey, 2015).

The rules of the race stipulated that all pilots must have had at least 50 hours worth of experience on their relative aircraft, according to Williams account this was fairly easy to achieve as the Harrier still had to be tested to its limits on air-refuelling runs and endurance flights, to make sure it was up to the task at hand (Marston, 2015).

Further problems were added by the lack of acceptable landing spaces on either side of the Atlantic. After much red tape and frustrating dead ends, a landing site in New York was located, a jetty on the east river just off 25th street east in Manhattan.

Unlike its competitors, the Harrier had one unique advantage in finding a suitable landing location, it could both take off and land vertically.

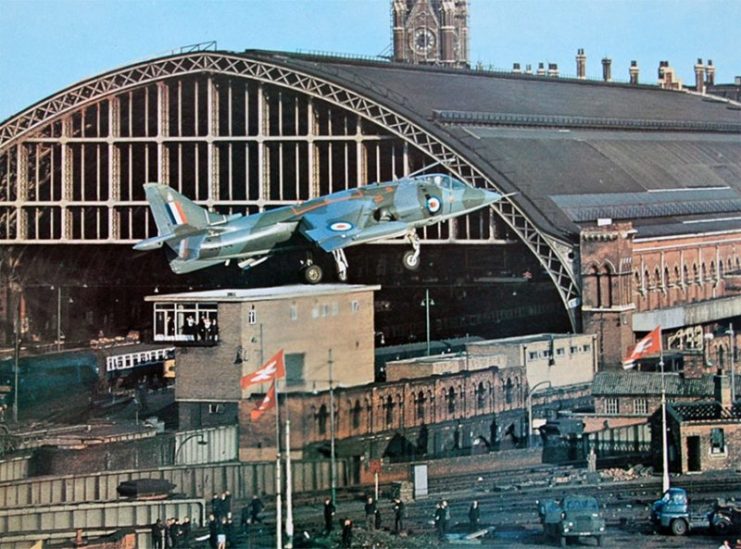

The difficulties in securing a landing site in the US paled by comparison to the problems faced at home. The location that was finally settled on was a disused coal yard at St Pancras railway station. There was still some resistance by officials in the UK, however, such reservations were abandoned when the flight team threatened to publicise the level of cooperation they had received from authorities stateside when their counterparts at home had been quite the opposite. (Ian M, 2012).

The Harrier to undertake the race was upgraded with a more advanced navigation system and a heads-up display. It was further tested to confirm that consumption rates were all within acceptable parameters. The air to air refueling system was also tested repeatedly to avoid any mishaps during the race itself. Victor tanks were used for the refueling purposes, by a stroke of luck the limiting speeds for both the Harrier and Victor was about the same, allowing an easy in-flight connection. (Dow, 2009)

The race refueling plan itself was rather complicated, involving a large number of refueling aircraft to support the harrier in its transatlantic journey. Three tankers were airborne during the harriers take off, these were required to refuel the harrier immediately after it reached the top of its climb due to the immense amount of fuel that vertical take-off consumed.

These three tankers were refueled by another set of three tankers, and the first three then accompanied the harrier across the Atlantic Ocean. The lack of long-range fuel tanks on the harrier resulted in a plan that involved seven refuelings between London and New York (Henley Standard, 2017).

In order to cater for the possibility of unserviceability after crossing the Atlantic, a spare Harrier was flown to New York before the race began by Lecky-Thompson, this served as a dress rehearsal for the race itself and provided a potential back up if things went wrong. According to Graham Williams, the two men had “a very good sinner given by Hawker Siddeley, the maker of the aircraft, before pouring Tom onto a BOAC aircraft back to the UK” (Marston, 2015).

After a few weeks of rehearsals and final checks, Lecky-Thompson flew his leg of the race on Monday the 5th of May 1969. According to reports, it was a clear day with ideal weather, he landed without incident at the landing pad, set up for them in New York and raced off on the back of a motorbike to the top of the Empire State Building, the designated “finish line” for his leg of the race.

Before the second leg of the race, Williams was required to move the harrier from its landing point in Manhattan to Floyd Bennet airfield, it was at this point he received a taste of what was in store for him. The cockpit was full of coal dust from St Pancras. It appears the disused coal yard wasn’t quite as ideal a landing site as had previously been thought, especially for an aircraft that takes off vertically, now in a cloud of black dust.

The second leg was delayed by the less than ideal weather conditions. It was during this time that it occurred to the two pilots to put on a bit of a spectacle for the onlookers the race had naturally drawn the attention of. The British ocean liner, Queen Elizabeth II was due to arrive in New York in its maiden transatlantic voyage.

The pilots set about getting the necessary clearance and on the day the QEII arrived in New York, it was greeted by two Harrier Jets hovering over it as it entered the East River. It was noted that the pilots did not ask permission from the RAF for their stunt, however, due to the publicity the act gained, no forgiveness had to be asked.

Unfortunately for Williams, the return leg was further delayed by adverse weather conditions. With time running out the decision to take the return journey regardless of weather conditions was approved. Williams clocked out of the Empire State Building and began the race to the landing site in the back of an E Type Jaguar, getting caught at every red light between the Empire State building and the harrier, a point that would prove fatal to the race (Marston, 2015).

Williams’s takeoff was made difficult by the rain and wind, but he made it to 36,000ft over Boston without much issue. The next problem would be finding the tankers through thick cloud and rain. After locating the required Voyagers and refueling, it was business as usual whilst crossing the Atlantic.

Luckily for the exasperated pilot, the conditions over London were much better and he had no issue finding the landing site at St Pancras. After pulling off the fastest vertical landing ever carried out at the time (Tangmere Museum 2018), Williams jumped on the back of a motorbike that took him to a helicopter, which in turn took him to the clock in point in London. He exited the helicopter, running past the crowds eager to see his arrival, took the lift to the top of the tower and clocked in at a time of 5 hours, 49 minutes, and 58.52 seconds (Glancey, 2015)

Tom Lecky-Thompson had won the London to New York route, but Gordon Williams had lost the return journey to a passenger in a Victor strategic bomber. Later analysis had shown that it was the journey from the Empire State Building to the Harrier take off point in Manhattan that cost the valuable time.

However, in Williams own words “it did not matter really because we had the opportunity to demonstrate the Harrier’s unique capabilities” (Marston, 2015). An interesting first flight for one of the RAF’s most iconic aircraft.