War History online proudly presents this Guest Piece from Jeremy P. Ämick, who is a military historian and writes on behalf of the Silver Star Families of America.

Bruce Berger, of Jefferson City, Missouri, has a number of reasons to take pride in the memory of his mother. Not only did she demonstrate her patriotism while supporting her country in the Women’s Army Corps in World War II, years later, after her husband passed away, she was able to raise three sons while at the same time completing a career in an American intelligence agency.

Born November 19, 1915 in Brooklyn, New York, Doris Van Wickel was the daughter of Jesse Van Wickel, who was at the time serving as a Foreign Service Officer for the United States. Due to his chosen career field, his daughter was exposed to many cultures while growing up in several different countries.

“My mother lived in several places in her youth to include Shanghai, China; Jakarta, Indonesia; The Hague; Netherlands East Indies; and England,” said Berger. “Until 1939, most of her time was spent outside of the United States,” he added.

Records maintained by Van Wickel indicate that in the early 1930s, she attended the Malvern Girls’ College in Great Malvern England and later completed coursework at George Washington University in Washington, D.C., and Columbia University in New York.

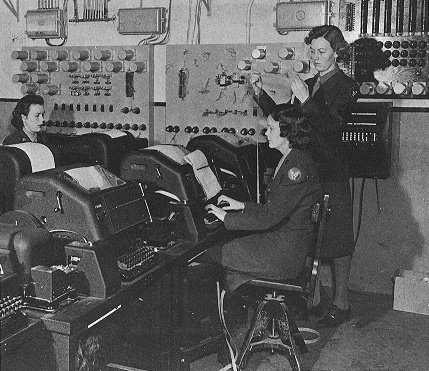

During her early years abroad, she acquired proficiency in seven languages to include German, French, Dutch and Chinese. She also worked for companies in Holland before returning to the United States, where she was hired in 1941 by the Military Intelligence Division of the War Department in New York.

“The work she did with the War Department was confidential,” said Berger. “In 1942, she became an assistant economic analyst with the Board of Economic Warfare in Washington, D.C. There she acted as an assistant chief for the Southwest Pacific Unit and researched conditions of the occupied Netherlands, East Indies and M alaya.”

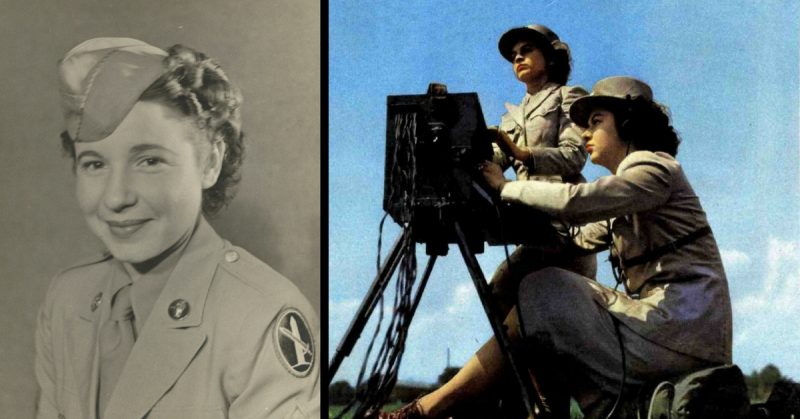

In October 1943, she made the decision to enlist in the Women’s Army Corps (WAC)—an organization created during World War II to allow women to support the war effort by serving in non-combat positions. As Berger explained, his mother completed her WAC boot camp at Ft. Des Moines, Iowa.

Military records indicate Van Wickel was discharged at the rank of technical sergeant on February 16, 1945 and the following day was appointed a second lieutenant. She remained on active duty as an intelligence research analyst until February 18, 1946, spending her entire period of military service at the Pentagon and achieving the rank of first lieutenant.

“While my mother was with the WACs, she met my father in Washington, D.C. after he whistled at her as she walked into a hotel,” said Berger. “Apparently, they dated for awhile and then married.” He added, “My father had served in the Army and after the war worked for the Census Bureau. My mother was eventually discharged from the WACs after she became pregnant with my oldest brother.”

The family remained living in the Washington, D.C. area where Van Wickel Berger’s first son, Ken, was born in 1946; a second son, Darrell, born in 1948; and Bruce, the youngest, was born in 1949. Sadly, Berger explained, his father passed away from Hodgkin’s disease in Janauary 1953, leaving behind their mother to raise three young boys.

“After my dad passed, my mother worked a couple of months for the Census Bureau and was then hired by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) in the spring of 1953,” Berger said. “She went on temporary duty assignments to places like Iran, Hong Kong and Thailand while us boys went to boarding school at Girard College in Philadelphia.”

The intrigue of their mother’s new chosen career field soon drew the boys into an exciting adventure when she brought them to live in Saigon in early 1962. While her sons were attending school during the day, Van Wickel Berger was involved in operations that remain shrouded in relative secrecy.

“She never talked too much about what she did and always joked that if she told us, she would have to kill us,” Berger chuckled.

Berger and his brothers have pieced together many facets of her service in Vietnam, which included her invovement in coordinating flights for “Air America”—a covert passenger and cargo operation operated by the CIA during the Vietnam War. The pilots, Berger noted, would deliver goods needed by various hamlets and bring their produce back into towns, collecting military intelligence during the process.

When the situation in Saigon grew more dangerous in early 1965 following bombings of locations such as a movie theater, Van Wickel Berger sent her children back to California to live with her brother. In 1967, she was sent to Udorn, Thailand, where she worked closely with the 7th Radio Reseach Field Station and was involved with radio intercepts.

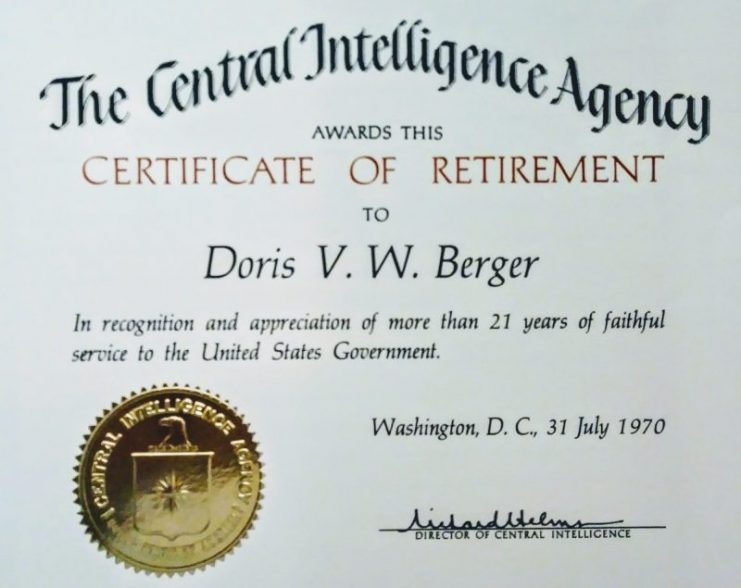

“My mother returned to the United States in 1970 and worked at the CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia, retiring later the same year,” said Berger. “She then went on to work for them as a contractor for a couple of years before retiring to Florida.”

The former member of the WACs and CIA agent passed away in 1989 from emphysema and was laid to rest alongside her husband in Arlington National Cemetery. As Berger went on to explain, although his mother may have at one time embraced the possibility of a “traditional” lifestyle of raising a family, the adventure that became her life demonstrates she was a woman before her time.

“When my father died, I think that my mother felt the American dream wasn’t really holding true for her—being married, having a nice house and raising children. But,” he paused, “I’m not really sure that ideal would have lasted for her.”

He continued, “My mother would joke during the 1960s and 1970s, at the time when women were burning their bras for equality as part of the women’s liberation movement, that she was working as a field operative for the CIA in several war zones.

“She was a trailblazer as a woman, not only because she served her country in uniform in the WACs, but she went on to demonstrate the value women could offer by working for the CIA at a time when women really had to fight to get a job that wasn’t just clerical in nature.”