By Jeremy P. Amick

A travesty in the preservation of military history is failing to capture the stories of our nation’s combat veterans before they are silenced by the grave. Fortunately, the voice of one local veteran has endured, thanks to the foresight of placing to paper his personal military experiences during combat—a legacy that concludes with a brother’s visit to the war memorials in the nation’s capitol.

Born September 1, 1923 in Columbia, Mo., Raymond Miller graduated high school in 1941. According to his biography titled “Action in Europe,” he worked in several low profile jobs, eventually entering a machinist program sponsored by the U.S. government.

“Raymond was one year younger than me and was a starting tackle for the Columbia Hickman (high school) football team,” recalled his brother, Robert Miller of Jefferson City, Mo.

Completing the course, Miller “took a job in defense at Curtiss-Wright Aircraft Company in St. Louis,” he wrote in his book. In September 1943, he wedded his fiancée, Helen Lewis, and was drafted into the U.S. Army the following year, after having received a deferment “for defense employment.”

Raymond’s writings explain that as a young draftee, he entered service in July 1944, traveling to Camp Hood, Texas, to undergo his conversion to a United States soldier by completing several weeks of basic infantry training.

Weeks later, he reported to Fort Meade, Md., to receive his issue of clothing and equipment. From there, he boarded the USS Wakefield anchored at Boston Harbor—a luxury liner turned troop carrier bound for the war in Europe carrying thousands of soldiers.

“Aboard the ship, everywhere you looked, there was a poker game or dice game in progress,” Miller recalled, describing his time aboard the ship.

When the inexperienced soldier arrived in Liverpool, England less than two weeks later, he moved by train to Southampton Port, loading on a British troop ship for movement across the English Channel.

On December 21, 1944, five days after the Germans launched the major offensive known as the Battle of the Bulge, Miller arrived at an infantry replacement center, where he received his rifle and assignment to Company C, 334th Infantry Regiment of the 84th Division.

As the company prepared to enter combat, Miller wrote that a lieutenant who, after asking Miller his name, stated, “You are the squad leader of the new men in 3rd squad” — an unexpected appointment that found the soldier serving in a leadership capacity without any previous combat experience.

His baptism of fire came on January 7, 1945, when he participated in his first combat in the town of Marcouray, Belgium, fighting from foxholes while enduring both enemy artillery barrages and the frigid weather.

“I was very cold, tired and hungry,” said Miller. “It was impossible to dig a foxhole in the frozen ground,” and he and a fellow soldier found a bomb crater full of snow, crawling inside to benefit from some semblance of protection.

He remained with his company for the remainder of “the Bulge” and, the following month, became part of a river crossing that characterized the violence and dangers of the remainder of his time in Germany.

On February 23, 1945, Miller was part a group of Company C soldiers scheduled to cross the Roer River in boats as part of an assault on a nearby German village. Departing in the early morning, the boats became targets for shelling and rifle fire as soon as they touched the frigid water. By the time the nightmarish incident ended, Miller’s boat was separated from the group and several soldiers had been killed or wounded.

Miller and his group eventually reunited with the company and went on fighting across Germany. During the early days of May, the “84th Division met the Russians at the Elbe River,” heralding the end of the war “for all practical purposes,” Miller transcribed.

Throughout his remaining weeks in Germany, Miller kept busy playing on the regimental softball team and served with a quartermaster company as part of the occupational forces. In June 1945, he accrued enough points to return home.

“After he came home from the war,” said Miller’s older brother, Robert, “we both played softball on a team in Columbia. Raymond played third,” he continued, “and I played left field. He knew all the players on the opposing teams and how they played, and would tell me where to play (to intercept their hits).”

In later years, the younger Miller would go on to work for the postal service. His first wife, Helen, passed away in 1972, and he retired from his postal job the following year. The veteran then moved to Florida where he met and married his second wife, Audrey, who passed in 1999. Though he had no children, Miller remained in Florida until his death on July 26, 2007.

“Before he passed,” said Robert (who served with the Army’s 20th Armored Division in WWII), “we would talk on the phone every night … about the war and things.” He added, “He had said that he didn’t know where he wanted to be buried, so I brought him here (Jefferson City) to be buried with full military honors.”

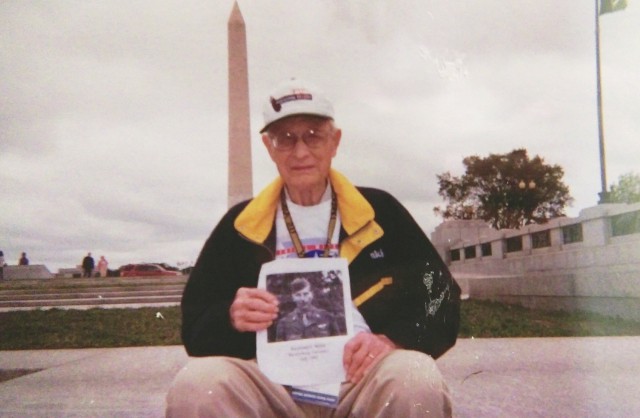

Although the Battle of the Bulge survivor never received the opportunity to visit, in person, the World War II memorial in Washington, D.C., his older brother devised a way for them to make the trip together.

“I knew Raymond would have wanted to have been on the (Central Missouri) Honor Flight,” Robert remarked, “so I brought his military photograph with me and had our pictures taken in front of the memorials.

“That,” he concluded, “made me feel as though he was with me … that he we had the honor of making the trip together.”

Jeremy P. Ämick writes on behalf of the Silver Star Families of America