War History online proudly presents this Guest Piece from Jeremy P. Ämick, who is a military historian and writes on behalf of the Silver Star Families of America.

When Virgil Koechner turned 17 years old, he informed his father that he was tired of working on the farm, asserting it was an ideal time to strike it on his own and to “see the world.” Leaving his Tipton, Mo., area home, Koechner thought that he could fulfill his wanderlust by enlisting in the Navy—a decision that would soon carry him half a world away.

“My oldest brother had been drafted into the Army during World War II and was injured while serving with the Ninth Armored Division,” said Koechner. “Since I knew I wanted to join the military and get away from home, I figured I would have a better chance of survival if I was in the Navy,” he grinned.

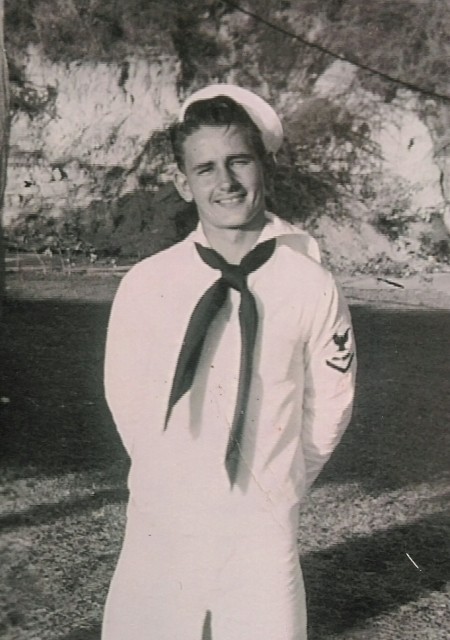

Following his enlistment in April 1947, the aspiring sailor completed his boot camp at San Diego before traveling to Memphis, Tenn., where he spent the next several weeks attending radio school and learning to send and receive messages through Morse code.

“They (the Navy) put me in the radio school,” Koechner affirmed. “It’s not something that I asked to do.”

Finishing his training in late summer, Koechner’s quest for excitement entered its first stages when he was assigned to the aircraft carrier USS Princeton (CV-37), spending the next year repairing radios in the ship’s “radio shack.”

“That’s where I was (aboard the Princeton) when Mao Tse-tung and Chiang Kai-shek were fighting it out in China,” Koechner recalled. “They sent us over to Tsingtao, China in 1948, to basically serve as a show of force.” (In 1949, Mao Tse-tung established the People’s Republic of China while Chiang Kai-shek and his followers formed a separate republic after fleeing to Taiwan.)

In 1949, he was transferred as a radioman to the aircraft carrier USS Valley Forge (CV-45), completing only a single cruise with the ship before he was transferred to a seaplane squadron in San Diego.

“We had nine (sea)planes and about 125 sailors—ground crew, pilots and all,” said Koechner. “The planes were called ‘PBMs,’ or ‘Patrol Bomber, Martin,’” he added.

The members of the squadron were soon on their way to the Philippines, spending several months conducting patrol maneuvers and training while operating from the naval station at Sangley Point.

“On Sunday, June 25, 1950, I was sitting at a bar in the Phillippines and was very happy that our squadron had just completed months of deployment and would be returning to the states soon,” Koechner said.

“That’s when a crewman from my plane walked in and said that the Korean War had broke out and that we were leaving for Korea in the morning.”

For the next several months, Koechner’s seaplane squadron was assigned to clear Korean coastal areas of mines that had been placed by North Korea. The PBM was equipped with a .50 caliber machine gun that was used to fire on the floating mines, thus detonating the device and removing the threat to Amercian ships.

Though it is uncertain as to the total number of mines placed during the war, in the book “The Sea War in Korea,” authors Malcolm Cagle and Frank Manson describe a “massive field of more than 3,000 mines” that had been laid off of the North Korean port city of Wonson, all of which was done “under the direction of Soviet naval experts.”

“I was assigned to the radio position, relaying our position back to base and letting them know what was going on … what we were seeing,” Koechner said.

Koechner and his fellow crewmembers received confirmation of the importance of their task on October 10, 1950, while operating with the USS Pledge—an American minesweeping vessel—near Wonsan Harbor.

“The Pledge struck a mine and was sinking,” Koechner solemnly recalled. “A North Korean gun emplacement on the shore began firing on the survivors. Our PBM flew over and strafed the position with our machine gun and took out the gun,” he added.

In late 1950, Koechner’s squadron was called upon to fly into the Chosin Reservoir to help rescue Marines wounded in battle after they were surrounded by enemy forces; however, Koechner explained, “somebody forgot to tell the admiral that the reservoir was frozen over and we could not land on the ice.”

Remaining available for the next two weeks, the reservoir never thawed enough for Koechner’s squadron to make any landings; however, the Marines were eventually able to fight their way through their encirclement.

After he was sent back to the United States in 1951, the sailor finished out his enlistment at Moffett Field, Calif., receiving his discharge in April 1952. He returned to Tipton, Mo., and joined an Army Reserve unit for a few weeks, but after “sleeping on the ground” during a training exercise at Ft. Leonard Wood, decided that Army life was not for him.

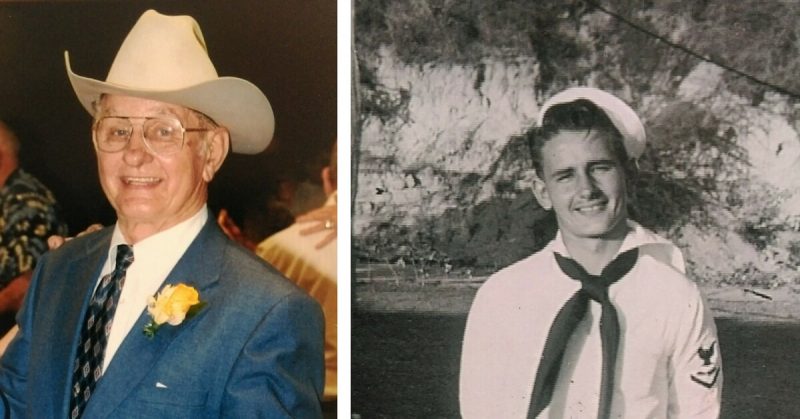

In 1956, the Korean War veteran married his fiancée, Mary Jane Hartman, and the couple raised six children together. Following his discharge from the Navy, Koechner was employed by Bell Telephone Company and remained with them for 44 years.

Conceding his experiences in the Navy during the Korean War do not fit the mold cast by many of his fellow servicemembers, Koechner affirms that he recognizes the importance of the work of the seaplane squadrons during the conflict.

“In my judgment, we were successful in clearing the mines and preventing our ships from hitting them,” he said. “And although it wasn’t our bailiwick to take out the North Korean gun emplacement (when the USS Pledge struck a mine)—that was a job for the (fighter) jets—I’m sure our quick actions certainly saved the lives of many of those sailors.”

He added, “There’s not many 17- or 18-year-olds that have these types of experiences happen to them … except in the military.