War History online proudly presents this Guest Piece from Jeremy P. Ämick, who is a military historian and writes on behalf of the Silver Star Families of America.

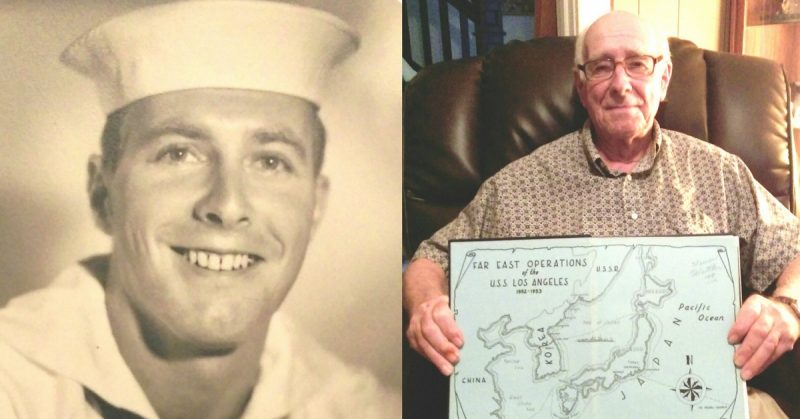

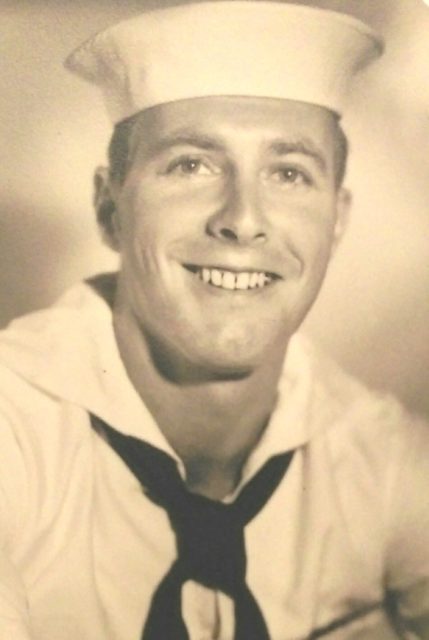

As a young man at the outbreak of the Korean War, Vernon Walther was not surprised when he received a notice to report for his military physical. Since many of his acquaintances were already serving in the armed forces, he assumed it would only be a matter of time before he would be called to join them.

“Everybody was expecting it back then, you know,” Walther said of his notice. “It wasn’t like it was something that just came out of the blue.”

After passing the requirements for his military physical in April 1951, Walther recalls asking the draft board clerk for Cole County, Mo., how long before his draft number would likely be selected.

“She told me that my number would probably come in the next round,” said Walther. “Instead of waiting to get drafted into the Army, I decided to go ahead and enlist in the Navy.” Grinning, he added, “I ended up doing a four-year enlistment rather than the two I would have done had I waited to be drafted.”

In August 1951, the 21-year-old recruit left his family’s farm on the east end of Jefferson City, Mo., and traveled to the Naval Training Center in San Diego, where he remained for the next several weeks as he was molded into a sailor. Upon completion of his boot camp in November 1951, he received assignment to the USS McKean—a World War II-era destroyer.

“That thing was like riding a Brahma bull,” Walther laughed. “It was small enough that whenever it sailed through rough waters, it was bucking all the time.”

Since the new sailor did not have an official job classification (known as a rating in the Navy) while aboard the ship, he became what he describes as “the lowest of the low,” and was assigned to a position called the “deck force.”

“I spent a lot of time chipping paint and then painting it, and then would start all over doing it again,” he said. “Luckily, I was only on that ship for eight months before it was decommissioned.”

The end of the USS McKean heralded an opportunity for Walther as he was then able to attend ten weeks of “commissary school” in San Diego, which provided him with the training to serve as a cook aboard a ship.

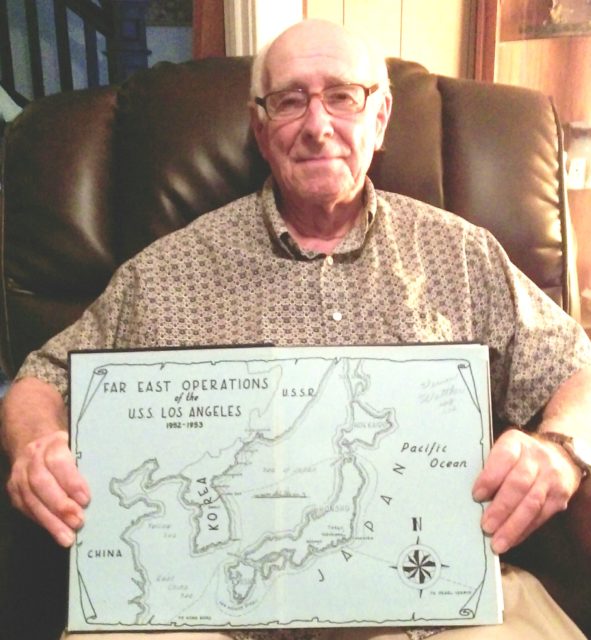

When finishing the school in the fall of 1952, he was assigned to the galley aboard the USS Los Angeles (CA-135), a WWII-era heavy cruiser that had been recommissioned for the Korean War. As Walther explained, the ship soon sailed for Pearl Harbor while he and his fellow cooks worked together to prepare meals for the ship’s complement of more than 1,100 sailors.

Days after arriving at Pearl Harbor, they set sail for Yokosuka, Japan, to take on supplies. From there, they traveled through the Straits of Shimonoseki (a length of water separating four of the main islands of Japan) to begin patrols along the eastern coast of the Korean peninsula. During these patrols, he said, they would use the ship’s guns to destroy enemy coastal positions.

“We spent a lot of time around Wonsan Harbor and got hit a couple of times by enemy shore batteries,” the former sailor recalled. “The first time no one was wounded but they put a fair size hole in the radar shack. Less than a week later,” he continued, “we were hit again and it damaged the superstructure of ship. That time 18 sailors were wounded.”

As Walther explained, when General Quarters (battle stations) was announced, he would leave the galley, grab a helmet and life vest, and then head “topside” to help pass shells to one of the gunner’s mates.

“This was over 60 years ago and I can still hear those splatters of water as the enemy shells kept getting closer to the ship,” he said. “Then,” he grinned, “it became like the Fourth of July and every one of our guns opened up and took care of any of the enemy firing positions.”

On one occasion, Walther noted, they had a Korean fishing vessel under surveillance. When it was discovered that the ship was laying mines intended to sink American ships, it was “blown out of the water” by the guns of the Los Angeles.

When their overseas duty was finished in May 1953, the crew of the Los Angeles returned to their home port of Long Beach, Calif., where Walther received a promotion and orders to report to Guam to serve in the galley aboard the USS AFDM-8, which was floating dry-dock used to repair naval vessels.

“I was cooking for about 75 sailors (in Guam) instead of the nearly 1,200 on the Los Angeles,” he said.

Completing his enlistment in July 1955, Walther returned to the United States. He went to work in the landscaping business for nearly a decade and eventually retired from the Jefferson City Street Department after 27 years of employment. In 1960 he married Lorene, who passed away 12 years ago, and is the proud father of three stepchildren.

Many veterans choose to view their own participation in the country’s military history in an undistinguished light and Walther is certainly no exception. He humbly stated, “At that time, when you were called to serve the country, you just went and did it and there was no big deal made about it.”

The veteran admits that throughout the years, he has been somewhat hesitant in sharing the details of his experiences aboard the USS Los Angeles, but he now realizes the importance of preserving the integrity of such accounts while they still exist through firsthand recollection.

“For fifty years or so, I never talked about what happened … such as when the Los Angeles was hit,” Walther said. “None of that really seemed very important to me at that time. “

Fervently, he concluded, “But when you get a little older, you begin to think that maybe somebody ought to know a little bit about what went on while we were in Korea or else it might be something that disappears from history forever.”