War History Online presents this Guest Article from Eugene Jones Baldwin

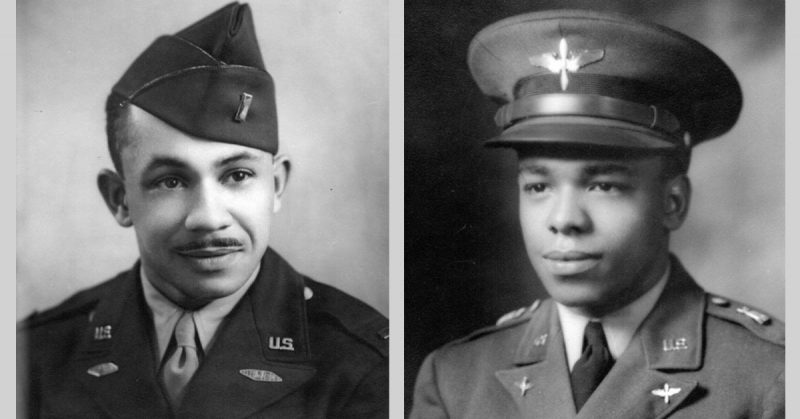

Arnold and George Cisco grew up in mostly white, rural Jerseyville, Illinois, graduating with honors from Jerseyville High School in the 1930s. They both attended the University of Illinois. Arnold received a bachelor of arts degree in languages and graduated Phi Beta Kappa. George earned a Bachelor of Science degree. The boys’ father, Roscoe Cisco was a noted piano player and music teacher. He also was a caretaker for a well-to-do white St. Louis family’s Jerseyville summer house, where the boys and their younger brother Harlow were born.

When World War II began, the Cisco brothers were determined to fight for their country, in spite of the fact that the armed services were segregated. The Navy designated blacks to serve as cooks or laborers. The Army formed all-black units, one of which built the Alaskan Highway. The U.S. Army Air Corps, citing bogus sociological studies from Southern colleges, determined that blacks were not capable of flying. Never mind the hundreds of black student pilots who trained at institutions such as Howard University. Thus the flight cadets at Mouton Field in Tuskegee, Alabama were for show only.

Until Eleanor Roosevelt appeared, to inspect the field, and to the dismay of her Secret Service detail, climbed aboard the training plane of flight instructor Alfred “Chief” Anderson (as a kid, he taught himself to fly and land), and the two took off for a flight around Alabama. Upon returning to base, a Look Magazine photographer shot a photo of the smiling Mrs. Roosevelt and Chief Anderson. Whether or not the event was staged, the Tuskegee Airmen would soon be sent to join the war effort.

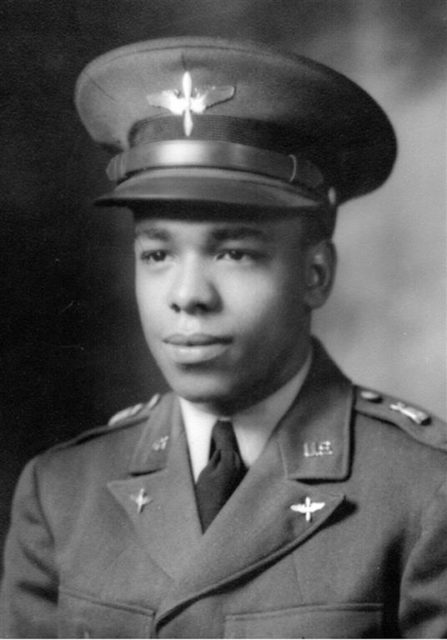

George Cisco initially joined the U.S. Army’s 761st Tank Battalion after graduating from officer training school at Fort Knox, Kentucky in 1943, with the rank of Second Lieutenant. Eventually, he transferred to the Army Air Corp and earned his pilot’s wings, officially becoming a Tuskegee Airman. He was killed on a training mission on August 16, 1944, when his Thunderbolt plane was hit by another plane as it landed at Walterboro Air Base in South Carolina.

Stationed with the 99th Pursuit Squadron at Ramitelli Air Base in Italy, Arnold Cisco and his squadron flew missions in P-51 Mustang fighter planes (the planes’ tails were painted red), guarding the U.S. B-52 5th Bomb Wing over Bucharest, Hungary, as the oil refineries below were bombed and destroyed, eliminating thirty percent of Germany’s oil supply.

Arnold Cisco earned the Oak Leaf Cluster of World War II, the Victory Service Medal and the European-African-Middle Eastern Theater medal. In 1946, returning from leave to visit his wife Hennie in Chicago, Cisco’s transport plane crashed when it hit electric wires during a storm.

The virulent racism endured by Tuskegee Airmen before, during and after the war, off base in the Southern states, was shocking. The war establishment, its policies dominated by Southern officers, made little effort to intervene.

Black soldiers, officers, and enlisted men alike were beaten by local mobs, and their families were threatened. Their status as officers and gentlemen meant nothing to the white citizenry, which scornfully referred to them as “niggers in uniforms.” Benjamin O. Davis, the commander of the Red Tail Angels, issued strict orders that his men were not to retaliate.

George Cisco’s widow Billie Cisco Smith told this writer, “We were stationed at one point at Camp Claiborne, Louisiana. The racial tension was so bad I was afraid to ride the bus. A friend of mine got slapped on the bus for not giving up her seat to a white person. I was pregnant with our daughter, and I was afraid.”

Ironically, French citizens, Britons, Spaniards – even the German enemy – treated the Red Tail Angels with grateful affection. German officers respectfully referred to the Tuskegee Airmen as “blackbirds,” and praised their dedication to stay in formation rather than perform solo acts of flying daring-do.

George and Arnold Cisco are buried in the Alton City Cemetery, their gravestones not indicating their status as Tuskegee Airmen. They both were killed in non-combat related plane crashes. It would be another thirty years before war historians documented the triumphant story of the Red Tail Angels. Had the brothers lived into the modern era, they would have been feted by presidents and celebrated by the nation’s school children.The Tuskegee Airmen Cisco Brothers Memorial Project is raising money for a commemorative marker at the graves of “The Cisco Kids.” An upright granite memorial will include photos of the brothers, an image of a Red Tail Angels fighter plane, and the words “Tuskegee Airmen.” The monument will be dedicated on Memorial Day of 2017. The cost of the memorial will be five thousand dollars. The committee has received some seed money, but your help is needed.

Please donate $5 or more by going online to GoFundMe, click on “Memorial,” and type in “Cisco Brothers.”

Author: Eugene Jones Baldwin is an essayist and columnist for The Telegraph, Alton, Illinois. He was a producer/interviewer for the National Tuskegee Airmen Oral History Project.